|

Reformation

and

Civil War

1539-1699

Pre-

1539

|

Please click here to look back at times before the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

|

|

The abbot's final home

Quick links on this page

Kett's Rebellion 1549

Haverhill's two churches 1551

Lady Jane & Queen Mary 1553

England Catholic again 1555

England Protestant again 1559

Suffolk has own Sheriff 1576

Royal Progress to Norwich 1578

Spanish Armada 1588

Suffolk's Puritan clergy 1597

Gunpowder Plot 1605

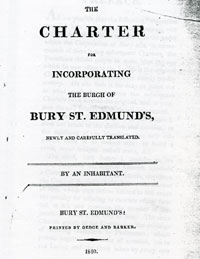

Bury's first Charter 1606

Bury gets two MP's 1614

Hard times in Bury 1622

Laud attacks Puritans 1633

First Civil War 1642

Second Civil War 1648

King Charles I executed 1649

Restoration of Charles II 1660

Euston Hall society 1671

King now runs Corporation 1684

Glorious Revolution 1688

Celia Fiennes Tour 1698

Foot of Page 1699

|

|

1539

|

Prior to the Dissolution of the Monasteries the Abbot of the Abbey of St Edmund upheld the King's law and imposed, and collected, taxes in the whole of the area later to become West Suffolk. The Abbot also sat as a peer in Parliament. The last abbot, John Reeve, was given a pension, and may have lived his remaining days in this house in Crown Street. He died within a few months of the surrender of the abbey, and may never have received his generous pension of £333.

During the time of the abbey any form of local self determination by the townspeople of Bury existed solely through the Candlemas Guild and later the Guildhall Feoffment Trust.

The property of the Abbey of St Edmund was surrendered to the Crown on 4th November 1539 but much of the wealth had already been confiscated in the previous year. After the dissolution in 1539, the rights of the Abbot returned to the Crown. The government of the town was largely ignored by the new owners of the abbey lands and privileges, and any joint actions continued to be carried out through the Guildhall Feoffees, largely without any formal legal backing. Over the next hundred years local government would replace the Abbots' Rule, but religious differences would cause bitter divisions in the country.

However, the town had now lost the use of the great library of the abbey, the access to the several hospitals which the monks had run, the grammar school was closed, and the various charities and good works of the monks were suddenly gone. The poorest in society would suffer most from many of these changes.

The library of books at the abbey does not seem to have attracted much attention from collectors at the time, and M R James thought that they were mostly acquired by local Bury people. It would probably be 50 years before there was much interest in them from collectors. Many manuscripts may have simply been disposed of as waste materials.

Unlike many other towns in England at this time, Bury was growing and prospering. It did this largely independently of the Abbey's decline and eventual closure. It was getting a steady stream of immigration into its cloth trade, and Gottfried believed that its population had by this time regained its pre-plague levels. In 1340 the population was about 7,150, falling to 3,000 by 1440. It was back at 7,000 by 1540.

Local agriculture was highly productive, depending on Bury for its market, and as a marketing centre for onward distribution. The wool and cloth industry was booming, again using Bury market for distribution nationally and internationally. The Netherlands trade was particularly important. The local gentry were happy to be involved in town affairs.

In Lavenham, Ipswich, Hadleigh and Bergholt, the independent weavers were restless. They had been used to being independent men, negotiating their production rates with clothiers, and controlling their own workrates. Now they were losing money. The clothiers had begun to set up their own weavers with looms, and fixing their pay. The independent weavers raised a petition against these new practices. "For the rich men, the clothiers, be concluded and agreed among themselves to hold and pay one price for weaving, which price is too little to sustain households upon, working day and night, holy day and week day, and many weavers are reduced to the position of servants."

|

|

1540

|

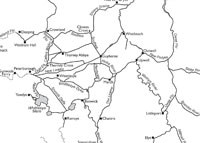

The Liberty of St Edmund, covering the area of West suffolk, had been the barony of the Abbot of St Edmunds up to 1539. The Liberty now came under the control of the Crown. The Sheriff had never had a direct control over the area of the Liberty. Instead, there had been a Steward of the Liberty, at least since the days of William the Conqueror. At first this post was appointed by the crown, and later by the Abbot. The duties included returning writs to the Sheriff, apprehending and holding lawbreakers, and convening the Liberty and hundred courts. After about 1120 it seems to have become an hereditary post. By 1536 the post of Steward of the Liberty had passed into the hands of Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk. The word of the monarch now held sway in the Liberty, but the area continued to hold itself somewhat separate from the rest of Suffolk. This situation continued up until about 1970, and the hereditary Stewardship of the Liberty also continued until that time, although its importance was purely nominal by then.

There was also a post of Steward, or Under Steward, of the Liberty of Bury St Edmunds, covering the area of the town rather than the whole of West suffolk. The Steward of the Liberty appointed his own Under Stewards to carry out his judicial duties. By the 20th century the stewardship of the Liberty of St Edmund and the Bury St Edmunds liberty were both in the hands of the Marquess of Bristol.

King Henry VIII now began to convert the seized properties of the church into cash. The details of each sale were settled by the Court of Augmentations which was responsible for the disposal of former monastic lands for the crown. Nicholas Bacon was Solicitor to the Court of Augmentations from 1537 to 1546, and he had local connections. His father was Robert Bacon, of Drinkstone, Esquire and Sheep-reeve to the Abbey of Bury St. Edmunds.

In 1540, some of the major local transactions carried out by the Court were as follows:

- In 1540 Sir Thomas Kytson was still extending his landholdings, and he bought eight of the previously monastic manors in Suffolk. These were Fornham St Martin, Fornham St Genevieve, and Fornham All Saints, Chevington, Hargrave, Risby, Sextons Manor at Westley, and Monks Hall at Santon Downham. He paid the tremendous sum at the time of £3,710. Unlike many other rich men who became landed gentry by buying up the newly privatised monastic lands, Kytson had first put his wealth into property in Suffolk when he purchased Hengrave in 1521. He also acquired the manor of Great Barton.

Sir Thomas Kytson died at Hengrave Hall shortly after making these transactions. He had been a rich wool merchant, trading in Flanders, and had built Hengrave Hall on the proceeds from 1525 to 1538. The house was left to his wife, Margaret, and his only son, also called Thomas, who was born soon after his death.

-

The manor of West Stow was bought from the crown by Sir John Croftes of that parish. Sir John was a substantial sheep farmer (flockmaster) who had leased the manor and lands in West Stow from the Abbot of Bury St Edmunds in 1526. He had made improvements to the old manor house, including the addition of the magnificant gatehouse in 1530, which still stands today. He must have been pleased to to be able to purchase the manor house and lands for £497.

-

Sir Thomas Jermyn of Rushbrooke bought the manors of Stanton All Saints and Bradfield St George from the crown.

-

Nicholas Bacon bought Ingham for £488 from the Crown.

- Thomas Bacon of Hessett bought the Manor of Hessett for £249.

- According to Sir John Cullum's History of Hawstead, Sir William Drury acquired the manor of Whepsted from the crown at this time. This manor was next to his holdings in Hawstead.

- The Drury family also acquired the manor of Hencote which was near to Hawstead around this time.

- The manor of Hardwick was granted to Sir Thomas Darcy, who was Lord Darcy of Chiche, as part of the monastic disposals, although the exact year is unclear. Hardwick would then pass through several hands before it would be bought by Sir Robert Drury in 1610.

More sales would follow in future years.

One of the disposessed monks of Bury Abbey, Thomas Hall, became Rector of Tuddenham St Mary. Dr Brinckley who had been the Warden of the Babwell Franciscan Friary, became Rector of Great Moulton in Norfolk. Ex-nuns may have found it harder to find work. They could not be ordained. The last Prioress of Thetford St George was Elizabeth Hoth. She had to move to Norwich to find a position.

The Bury born Bishop of Winchester, Stephen Gardiner, was a power in the land. In 1540, following the death of Thomas Cromwell, he was elected chancellor of the University of Cambridge. He was educated at Trinity College, and had been its Master since 1525.

He had achieved much of his early rise due to the patronage of the Duke of Norfolk, who had introduced him to Cardinal Wolsey. The Duke of Norfolk now persuaded Gardiner to support the idea of his niece, Katherine Howard, becoming Henry VIII's fifth wife.

|

|

Boy Bishop token

|

|

1541

|

More old church ceremonies were banned, including the Boy Bishop ceremonies widespread in Suffolk each December. During the Middle Ages it had been customary for churches and abbeys to elect a choirboy as Boy Bishop. He held office from St. Nicholas' Day (December 6th), to Childermas, (December 28th) also known as Holy Innocents' Day, when he usually preached a sermon and then "resigned". As a souvenir, the boy was apparently given a lead token, but in some places he was also given a supply of such tokens to hand out to his "congregation", as alms.

In England, the main centre of both production and use of these tokens seems to have been Bury St Edmunds, although they were issued in many places on the continent. In Bury the Boy Bishop was in existence by 1418, but the first tokens seem to have been issued from about 1480. They were distributed by the Boy Bishop and probably exchanged for sweetmeats or alms at the Abbey almonry or by charitable local merchants. The distribution of their findspots suggests that they were also used as small change.

Although now officially banned, this ceremony and related lead tokens seems to have been revived on a few occasions over the next few years.

In the sixteenth century the town of Haverhill continued to flourish. It obtained a royal connection on 27th January 1541, when the parsonage, lands and right to appoint clergy were granted to Henry VIII's fourth, and recently divorced wife Anne of Cleves.

Anne of Cleves, the fourth wife of Henry VIII, arrived in England in 1539 and married the King in 1540, though the marriage was never consummated. By July she was officially divorced. In January 1541, she was given the parsonage house at Haverhill and the right to appoint clergy. She also received a large amount of property in Sussex, Essex and other counties. She never came to Haverhill, preferring to live at Lewes, Sussex. It is probable that the parsonage given to Anne was burnt down in the fire in Haverhill in 1667. The house which today bears her name and is probably the finest building in the town today, was built in 1480, and did not become a vicarage until much later. It seemed to acquire the name of Anne of Cleves House as late as 1967, when it was put up for sale by an enterprising estate agent. It was recently occupied by American security firm HID Corporation Limited, but was on the market again in 2002.

The manor of Culford was bought from the crown by Christopher Coote, a Norfolk gentleman.

The manor of Lakenheath was granted back to the Dean and Chapter of Ely cathedral.

|

|

1542

|

In February, 1542, the Queen, Catherine Howard, was executed for adultery. Several of the Howard family were also arrested. The Duke of Norfolk was likewise out of favour with the King, but not arrested at this time.

War broke out with Scotland. The king could not wait for the rental cash flow to come through from his new monastic holdings. He had to sell it off to capitalise on it, to get enough to pay for war. So the great sell off continued. The Court of Augmentations which ran the process for the crown now went into overdrive. There were a flood of sales frm 1542 to 1547. Officials of the Court, like Sir Nicholas Bacon, became vastly rich during this process.

Sir Anthony Wingfield bought the Haberdon Manor at Bury from the crown.

Since 1500, prices had been increasing. However, the level of inflation rose dramatically around 1542 and would remain high for another 10 years. Some people believed that the continued enclosure of land for sheep farming reduced the supply of arable crops and thus pushed up prices. The Earl of Hertford, (later Lord Somerset) tended to be against enclosure and was lenient when enclosure fences were torn down by dispossessed farmers and labourers.

To make matters worse there were a series of droughts in the 1540's, and the resulting food shortages pushed prices up further. In 1542 the Thames dried up to a trickle, followed by widespread crop failures and many small farmers were forced out of business.

|

|

1543

|

If war with Scotland was not expensive enough, war with France came a year later in 1543.

The dry weather continued and rivers dwindled even further. A fire at Reepham in Norfolk consumed one church and most of the High Street, as the river was nearly dry and there was no water to extinguish it. Throughout the region starvation became a threat. Copernicus published a theory that the earth revolved round the sun, having studied the planets through a telescope which he had built.

On July 12th the King married Catherine Parr, his sixth and final, wife. The marriage ceremony was performed by the Bishop of Winchester, the Bury born Stephen Gardiner.

|

|

Nicholas Bacon

|

|

1544

|

Many of the former monastic lands came on the market as the King continued to cash in on his new assets. For this he relied upon the advice of the Court of Augmentations, set up under Nicholas Bacon to dispose of surplus monastic property. The King granted John Eyer, Receiver General in the County of Suffolk over 50 parcels of monastic land and property. As Receiver General, Eyer had to collect all the rents from the former Monastic property throughout Suffolk and Norfolk. This grant included all the rents due on the land and included the right to carry on collecting the old hadgovel rents, or ground rents, first granted to the monastery of St Edmund at least as far back as the Norman Conquest, and possibly earlier. Hadgovel was paid on property inside the town walls, while the farmland outside the walls was subject to a payment called Landmole. Hadgovel seems to have been one penny a measure of land per year, while Landmole was one penny per acre per half year. Thus the tenants on land merely got a new landlord, they did not get set free of their old duties. Many of these dues had been the cause of civil unrest under the rule of the abbey, and these burdens were now to continue, but now paid to secular landlords.

John Eyer was one of many who profited from the patronage of Sir Nicholas Bacon, a barrister connected to Drinkstone, just outside Bury, who also became a great land owner in the area. Nicholas Bacon was born at Chislehurst, in Kent, in 1509. He was of non-aristocratic but comfortable origins, the second son of Robert Bacon, of Drinkstone, in Suffolk, Esquire and Sheep-reeve to the Abbey of Bury St. Edmunds. He took a degree at Corpus Christi college, Cambridge in 1527. Nicholas Bacon was Solicitor to the Court of Augmentations from 1537 to 1546, which was responsible for the disposal of former monastic lands for the crown. Thus he was well placed to help his friends get land grants. When we use the term grant, this is not meant to mean that it was given away for free. Nearly all such monastic land was, in reality, sold to the highest bidder, or to those who were in the know. Eyer had to pay £675 8s 10d for this land plus parcels in the three neighbouring counties.

In 1544 Nicholas Bacon bought the former monastic manors of Redgrave and Rickinghall Inferior, the latter for £785. Bacon also acquired St Saviour's hospital in Bury, and because it was by now in bad disrepair, used it for building materials for his new house in Redgrave. At an unknown date he also bought Mildenhall.

Thomas Bacon of Hessett bought Netherhall Manor at Pakenham for £599.

Adam Winthrop, a London clothier, obtained the manor of Groton from the crown for £409. The family would play a part in the history of America in later years.

In 1544 both of Henry VIII's daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, were reinstated to the royal succession.

|

|

1545

|

Having taken over the possessions of the monasteries and abbeys, the various religious and social guilds in the country were dissolved and their possessions confiscated by the Crown. The Candlemas Guild was therefore dissolved but the Feoffees continued with their secular work. They tried to maintain hold of as many of their endowments as possible when the Guild was dispossessed.

On the passing of the act of parliament in 1545 enabling the king to dissolve guilds and their and colleges, Matthew Parker was appointed one of the commissioners for Cambridge. He was Master of Corpus Christi College and the Commissioners' favourable report may have saved the Cambridge colleges from destruction. Stoke By Clare College, however, was dissolved in the following reign. Parker had also been its Master and would receive a generous pension.

In Bury the Guildhall Feoffees tended to organise any public works that were needed. In other places such as Ixworth it was often left to the wills of better off individuals. Hugh Baker left 40 shillings in his will to make one bridge of lime and stone at the mill at Ixworth.

At Redgrave, Sir Nicholas Bacon began building Redgrave Hall, which would take until 1554, and cost him £1,253. Some of the materials came from demolishing the much run down St Saviours Hospital in Bury. Bacon was the solicitor to the Court of Augmentations, which was set up in 1536 to manage and dispose of former monastic holdings for the crown.

Nicholas Bacon also acquired Hinderclay and Wortham Abbots in 1545 from the crown. He paid £488.

Henry Payne, a lawyer from Bury st Edmunds, was granted the manor of Nowton for £648.

Among his many purchases of former monastic estates, Thomas Howard, Third Duke of Norfolk bought Rougham Hall manor for £1,651.

Sir Thomas Jermyn of Rushbrooke bought the manor of Rougham Eldo from the crown.

Robert Spring got Pakenham Manor from the crown for £1,432.

|

|

1546

|

Other monastic properties in and around Bury were granted to John and Andrew Manfield, and other disposals continued through to the 1570's. Eyer in particular began to sell off many of his scattered holdings and over the next 50 years there was much buying up of newly available property by adjacent owners in order to consolidate holdings and redevelop larger properties. The Abbey had by and large held on to anything it owned, making it difficult for much property exchange to take place until after 1539.

Other local gentry to buy up three or more monastic manors were Sir William Drury of Hawstead and Sir Thomas Jermyn of Rushbrooke. Jermyn himself spent over £1,000 on these, as did Robert Spring of Lavenham.

The manors of Hardwick and Horringer Magna were bought by Thomas Darcy, Lord Darcy of Chiche. He had bought Horringer Parva already, in 1540. Darcy would soon sell Horringer to the Jermyns of Rushbrooke.

Nicholas Rookwood of Lawshall bought the manor of Livermere Grange from the crown.

Other monastic lands were leased. For example the manor of Melford and Melford Hall, was leased to William Cordell, a Melford man and a rising solicitor.

In 1546 Sir Nicholas Bacon ceased to be the Solicitor to the Court of Augmentations. He got more monastic lands outside Suffolk and became Attorney to the Court of Wards and Liveries.

|

|

1547

|

Following the Act of Parliament in 1545 abolishing religious and social guilds, a further Act in 1547 extended the ban to the Chantries. These were usually small chapels with a resident or visiting priest, which wealthy men had established to ensure that prayers would be said for their souls. It was believed that this was a way to shorten the time that their souls were held in Purgatory.

When the Chantries were abolished, their lands and assets were seized by the Crown. This included a number of buildings in Bury St Edmunds, left to the town by beneficiaries like Jankyn Smythe and Margaret Odeham. Some of the chantries established for the souls of the deceased were intertwined with monies also left for the maintenance of almshouses and the relief of the poor. Without the income from some of these lands, there was no money for the poor relief, and something had to be done.

Henry VIII died on January 28th 1547 at the age of 56, having reigned over 37 years. His requiem mass was led by Stephen Gardiner, the Bury born Bishop of Winchester. He left only one young son, King Edward VI, who became king aged 8 years. King Henry's break with the Roman Church and the dissolution of the monastic system had been the greatest social upheaval in hundreds of years. Henry VIII had taken over monastic lands and made some Reformation of the Church, but he feared to go too far to avoid civil unrest. He did not want a repeat of the Pilgrimage of Grace of 1536.

Having taken over the Church's lands, Henry VIII had sold off about two thirds of all monastic holdings by 1547. Most of the £780,000 raised had gone on military supplies and soldiers' wages. About 1,000 people had acquired 1,593 grants of land. They had all paid for this except for only 41 grants known to be gifts. Sales were made at 20 years purchase, which is a high price if the net annual values were correctly calculated. (ie if the property made an income of £20 a year, you could buy it for £400.)

Troston Manor was bought off the crown by Thomas Bacon of Hessett, but there were few manors left to sell by this time.

In his will, Henry VIII appointed a Council of 16 equal ministers to rule during Edward VI's minority. However, Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, declared himself Lord Protector of the Realm.

Edward Seymour soon promoted himself to Duke of Somerset, and unwittingly made himself the focus of discontent, as he at first seemed to tolerate the enclosure riots and sympathised with the protestors' grievances.

In his later years King Henry VIII had backed away from further Protestant reforms. His infamous Six Articles of 1539 had been a re-introduction of Catholic doctrine, but under himself as Supreme Head of the Church.

Under the new king, Henry's policies were reversed and the Second Reformation of the English Church began. First came The chantries Act of 1547 that dissolved all the secular colleges and religious guilds, as well as the Chantries. This was important for Bury as it possessed one of England's 140 secular Colleges. This was the College of Jesus founded by Jankyn Smythe. It would close in 1548. A similar college at Stoke by Clare closed in that same year, despite the fact that Matthew Parker, Vice Chancellor of Cambridge University, was its Master.

Also to close, and its endowment properties sold off, was the Chantry College of Denston, founded in 1475 by John Denston, and located within St Nicholas' Church at Denston. As this was also the parish church, the church itself survived the confiscations.

It is possible that there was a College of secular priests at Chevington, but there seem to be no records. College Farm and College Green still exist in the village. The church records for 1595 record a "Henry Paman of the college, deceased."

Injunctions of July 1547 ordered the destruction of all shrines, paintings and pictures of saints.

These Protestant Reforms were opposed by the Bishop of Winchester, Stephen Gardiner. He had played perhaps the biggest part in drawing up Henry VIII's Six Articles, and he remained true to their principles. Gardiner, who was born in Bury, fell out of favour, and was thrown into prison. At first he was in Fleet Prison, but following an enquiry, was moved into the Tower of London, where he stayed throughout the reign of Edward VI. In 1555 he was formally removed from the office of Bishop of Winchester.

Thomas Howard, the Catholic third Duke of Norfolk, was also imprisoned in the Tower, although in his case, he was probably already going to be arrested by Henry VIII on a charge of treason.

|

|

1548

|

At Bury St Edmunds, the plight of the town's poor was becoming critical following upon the Crown seizure of the chantry buildings and associated lands. The parishioners and church wardens of both the town's churches agreed to sell off the silver and gold plate used in church services to produce assets which would provide the income needed to support the parish churches and their charitable endeavours. The plate of the parish churches of St Mary's and St James was duly sold off and raised the goodly sum of £480.

It was duly agreed to buy the chantries of Margaret Odeham and Mr Beckett, and the gilds of St Nicholas and St Botolph, together with other lands which had been supporting the Morrow Mass Priests of St James' Church.

The Seymour brothers Thomas and Edward were hungry for power. Thomas was jealous of his brother Edward who had made himself Lord Somerset. Katherine Parr married Thomas who thus became stepfather and guardian to Elizabeth. He was 40, she 14. After Katherine Parr died following childbirth, Thomas Seymour wooed Elizabeth. In May, Lord Somerset granted a pardon to rioters in Cornwall who had risen up in the last months of the old King's reign against the enclosure of the commons. Anti-enclosure riots were spreading nation-wide and several other pardons were granted. Rioters grew bolder as they began to get their way.

At church, the Reformation continued.

In February 1548 the Privy Council ordered the removal of all religious images from churches.

|

|

1549

|

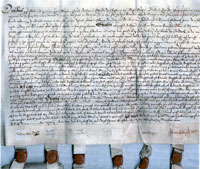

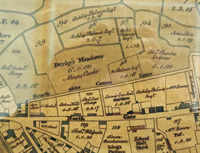

The Crown now sold the chantries of Margaret Odeham and Mr Beckett, and the gilds of St Nicholas and St Botolph, together with other lands, to Feoffees in Bury St Edmunds. These were to be a body of 24 of the most discreet and substantial persons of the town, with 12 drawn from each of the two parishes. The sale of church plate in the previous year had provided the money for the purchase, but the Guildhall Feoffees would decide how to make use of the lands acquired, the rents payable, and the usage of those rents. The control of these lands by such a narrow body of wealthy and conservative men would become an issue in future years.

In a list of Charities belonging to the Borough in the council yearbook for 1896/97 this purchase was known as "The Town Estate", and "consisted of certain lands and tenements in Skinner's Row, Baxter Street, Northgate Street, the Great Market Place, Garland Street, Horringer and Westley, and the Guilds of St Nicholas and St Botolph, which had become forfeited to the Crown, being devised for 'Superstitious Purposes', and were by deed dated 26th August, 1548, purchased of the Crown by Trustees with money raised by the sale of church plate, for the charitable and other purposes mentioned in the deed.

Thomas Seymour was arrested after killing one of the king's dogs in strange circumstances in the King's apartments, and suspicion also fell on Elizabeth. In March 1549 Somerset signed his brother's death warrant.

By 1549 anti-enclosure riots were commonplace amidst the economic and religious turmoil of the times. Events were moving faster than the Council of Ministers could address any reforms, such as the commissions on enclosures.

There was an increase in the reformation of church practices. All images and shrines were now banned as were processions and elaborate church equipment. Services were to be in English. Another Act allowed priests to marry, and in Suffolk probably about a quarter eventually married.

In Cornwall there had been several tense years when the religious reformation was pressed home too harshly. A rumour in 1549 that a new English prayer book was to brought in at Whitsun, caused a rebel camp to be set up. The First Act of Uniformity was duly passed in 1549 and made the first English language prayer book the required basis for church services. This was the Book of Common Prayer, a first national imprint of Protestantism. The rebels laid siege to Exeter in July and Lord Somerset sent a force to contain the situation. The situation was looking grim when another major rebellion appeared in East Anglia.

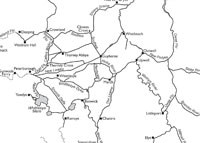

The East Anglian Uprising, known as Kett's Rebellion, started in Wymondham in July when enclosure fences were torn down. Robert Kett became involved when the mob turned their attacks onto his enclosure fences. Robert Kett was an unlikely man to lead an uprising. He was a 57 year old well-to-do merchant and landowner. Kett listened to the grievances of the crowd, and even helped them tear down his own fences. He then led them on to attack those of John Flowerdew, an old enemy of Kett's. On July 9th the mob, led by Kett, decided on a 9 mile protest march to Norwich, circling the city to rest overnight at Bowthorpe, 2 miles north west of the city walls. They pulled down the fences of the "town close", or former common of Norwich. A few days later they had moved to Mousehold Heath, an area of high ground to the east of the city of Norwich honeycombed with chalk and flint mines, but overlooking the city. Almost by accident a great rebel camp was set up here, and new recruits poured into it.

By mid-July another camp was set up a Ryston, just outside Downham Market. Soon a camp was established at Brandon, another at Bury St Edmunds, and on 14th July a major camp was set up outside Ipswich. The Ipswich camp was quickly moved to Melton, near Woodbridge.

Unlike the Cornish rebels, the East Anglians favoured the new English Prayer Book and adopted its use. They also issued proclamations and set themselves up as an alternative local government to that available from the gentry. The rebels, however, still saw themselves as supporters of the crown, but were vehemently against the excesses of the landed gentry. They drew up a list of 29 demands, many of them to do with enclosure of common land and the current high prices. Unfortunately the official response was high handed and only caused to provoke the rebels to stiffen their resolve. When the lists were rejected by the Crown the city of Norwich decided to have no more to do with the Great Camp, and shut its gates, and manned its walls.

Thus, with Norwich now closed to them, the rebels attacked Norwich on July 21st, and succeeded in storming it next day. They returned to camp with prisoners, arms and looted supplies, and sat there for ten days.

On 31st July the Royal Army finally arrived although only 1,500 strong, and was allowed to retake the city of Norwich, where they were harried by various skirmishes. Following the death of Lord Sheffield in one battle, the army withdrew to Cambridge.

On August 17th a rebel force took Lowestoft in their second or third abortive attempt to capture Great Yarmouth, the second largest town in Norfolk. By this time a much larger Royal Army, of over 10,000 men, was mustered in London, and they set out for Norfolk. The army was led by John Dudley, the Earl of Warwick, and by 24th August they were at Norwich.

Although the actual site of the rebel camp at Bury St Edmunds is no longer known, it is believed to have been the major rebel centre for West Suffolk. It was probably abandoned either as the Earl of Warwick's army approached from London, or because the Suffolk gentry managed to placate them without the antagonisms which provoked the camp at Norwich.

When Warwick broke into Norwich on 24th August, there followed a great deal of street fighting back and forth until the rebels retreated to bombard the city for 2 days from Mousehold Heath.

Some 1,500 Royalist cavalry reinforcements now arrived at Norwich. The rebels moved to the plain at Dussindale for a final battle about 2 miles east of the city centre on 27th August. Robert Kett probably had 10-15,000 men and around 20 cannon. Warwick had 6,000 trained men, mostly cavalry men, largely foreign mercenaries, with another 6,000 left holding Norwich. He had fewer cannon but more experienced gunners, and he had 200 hand gunners. Once the rebel field guns were destroyed by the royal artillery, the cavalry spearheaded the victory. About 3,000 men died, mostly rebels. Robert Kett was captured next day as was his brother William.

In the next few months, Lord Protector Somerset was overthrown and replaced as head of the Great Council by the Earl of Warwick, the victor of Norwich.

On November 26th, 1549, the Kett brothers were sentenced to death and on 7th December, William Kett was hanged at Wymondham and Robert Kett was hanged on the walls of Norwich Castle.

Thus did a protest march turn into bloody confrontation and death, each escalation seeming to occur without being clearly planned, or the consequences thought through.

The memory of "camping time" and the savage reaction to it by the authorities left widespread resentment in East Anglia for years to come. The area would continue to raise radicals and dissenters for years to come.

|

|

Ancient House

|

|

1550

|

Since the Dissolution in 1539, the monastic grammar school at Bury had been apparently closed and dispossessed. The townspeople had to petition the crown to get a replacement school lawfully established. Finally, in 1550, King Edward VI founded a new grammar school at Bury. From 1550 to 1665 this school was probably situated on the site of Ancient House in Eastgate Street, on the corner of Barn Lane. There is a plaque on the wall commemorating this school. The building was formerly the Guildhall of the Guilds of St Thomas, Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and St Peter.

King Edward VI was a strong Protestant, and was also responsible for the destruction of many books surviving from monastic days on the grounds that they contained superstitious images and ideas from the Papist era. In 1550 Injunctions were passed which even ordered the removal of alters from Parish Churches. Simple tables could replace them, provided they were not on the same positions.

The site of Bury's Abbey was leased by the crown to Sir Anthony Wingfield, a Suffolk man. He had been Sheriff of Suffolk and Norfolk in 1515-16, and a member of Parliament for Suffolk in 1529-35.

|

|

Rushbrook Hall in the 19th Century

|

|

blank |

It is not definitely known who built the first major residence on the site of Rushbrook Hall, but it has been credited to Edmund (Roberts) or Sir Thomas (Statham) Jermyn around 1550, and also apparently to a later date of about 1575, by Sir Robert Jermyn. This is the period when great houses were being built in a U or E shape, and E is the shape of Rushbrook. It was built in the older moated style.

The climate has not always been just as we experience it today. We all know about the Ice Age which was thousands of years in the past, but from about 1550 to around 1850 there was a cooler period, sometimes called the Little Ice Age. Prior to this time there had been a warmer period, called the Medieval Warm Period, from about 800 to about 1300.

After the mid 1500's there were colder winters than we are used to today, with great hardship for man and beast.

|

|

1551

|

In 1551, the people of Haverhill petitioned the King that the old St Marys church (previously referred to as St Botolphs) at Burton End be abandoned, and it was pulled down. Nothing of the original Burton End settlement now remains, though an excavation carried out in 1997 by the Hertford Archaeological Trust, uncovered many ancient skeletons and funeral relics. Pigot's Directory of Suffolk for 1830 stated that ruins of this church were still visible at that time.

May 12th 1551 "...Whereas the inhabitants of Haverhille, Suffolk, have informed the King that of the two churches in that town that the one called the Overchurche is too small to hold all the parishioners and is difficult to access; whereas the other church called Netherchurch (St Marys) is large enough for all and conveniently situated, that the inhabitants are not able to repair and maintain two churches and the Netherchurche shall then be the parish church of the whole town, and its rector shall have the tithes and profits previously enjoyed by the Rector of the Overchurche."

There is a plaque in the St James's Church at Bury recording that King Edward VI contributed £200 for the completion of the work on the nave, which had been going on since 1503.

In London, the Earl of Warwick, John Dudley, made himself Duke of Northumberland.

|

|

1552

|

Parliament passed the Second Act of Uniformity. Church attendance was made compulsory on Sundays.

A second new Prayer Book was introduced. Church vestments were already banned and alters had been replaced by tables in the previous year. The ancient Mass was effectively now replaced by a Protestant Holy Communion.

Sir Thomas Jermyn died at his newly built home at Rushbrooke hall. The family was Puritan in religion and there would be 16 generations born at Rushbrooke.

The Clothing Act of 1551-52 sought to impose further rules upon the production and sale of cloth. It was intended to stop the production of a range of inferior products and so imposed a comprehensive set of rules governing all cloth types, specifying compulsory sizes and weights of all types of cloth from Suffolk, Norfolk and Essex. The colours allowed were also specified, as were many of the methods of production which were now outlawed. Town inspectors had to seal the cloths with an "F" and charge 2d a piece for doing so. Local clothiers complained that their main competitors, the Dutch, suffered no such restrictions, and Dutch cloths were becoming more and more into fashion. These Dutch weavers were immigrants from The Low Countries, who were all Protestants, who could not continue to thrive under the Spanish Catholic rule there. The lead seals used by the Dutch clothiers were trusted to be accurate as these people became highly regarded for proberty and honest dealings.

|

|

1553

|

By 1553 the 15 year old King Edward VI was dying of TB. He was an enthusiastic Protestant and, on his deathbed, disinherited his Catholic sister Mary to avoid his reforms being reversed. The English church was totally reformed by now, both in the destruction of statues and decorations, and in the forms of worship. In 1553 Thomas Cranmer issued his Forty Two Articles of Religion which gave the English Church its final Protestant Theology. The legality of this act of disinheritance was questionable, and many people thought it the result of a plot. King Edward VI died on July 8th.

This was a time of intense rumour and speculation. Lady Jane Grey was the daughter of a cousin of the king, only 15 years old, and was born in the same month and year as Edward VI. She was the daughter of Henry Grey, the Duke of Suffolk. His wife was Frances Brandon, a cousin of King Edward VI. It was said that John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland, was behind the plan to replace Mary by Lady Jane. His son Guilford had been married to Lady Jane only two months previously, and now he ordered the Tower of London to be fortified, and was expected to seize Lady Mary. It was also rumoured that the king had died on July 6th, but the news was suppressed by Northumberland for two days, while he put his plans into effect.

Mary, a mature woman of 37, was at home in Hunsdon in Hertfordshire when news of the king's decision arrived, but rather than obey the summons to what she believed was imprisonment, she fled to Cambridgeshire. On 9th July she wrote to the Council in London asking for their allegiance as the true Queen. From there she went to the home of the Duke of Norfolk at Kenninghall in Norfolk. Norfolk had been imprisoned by both Henry VIII and Edward VI, because of his Catholic beliefs. His properties at Kenninghall and Framlingham had been passed to Mary. Sir William Drury of Hawstead took 100 men to Kenninghall to assist Mary.

On 11th July the Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk, Sir Thomas Cornwallis, with other local nobles, joined Ipswich Town Council in declaring Lady Jane Grey, the Queen of England. The people of the town were much less enthusiastic, and there were some disturbances. John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, was not popular in East Anglia, having been involved in the bloody suppression of Kett's protest camp in 1549, when he was the Earl of Warwick. By this time, John Dudley was in possession of the manor of Great Barton, for in 1553 he now exchanged it for the manor of Drayton Bassett. Thus did Great Barton apparently pass into the property of Thomas Audley. Great Barton would remain in the Audley family until 1706.

On 12th July, Mary moved from Kenninghall to the great castle at Framlingham. The Sheriff, Cornwallis, now relented his position and joined Mary's side.

By 14th July Norwich declared for Mary, and a throng of local nobility joined her at Framlingham.

Sir William Drury of Hawstead Place swore allegiance to Mary as Queen on 17th July. Mary ordered all captains to bring their men to muster under Sir William Drury and Sir William Waldegrave.

Mary Tudor was the rightful Queen in the eyes of much of the country, and poor manipulated Queen Jane was to reign for only nine days. Sir Henry Bedingfield had marched from Norfolk to Framlingham. Most of the East Suffolk nobles now supported Mary. They even turned the naval ships laying in Orwell Haven to cut off Mary's escape, into her supporters. Some 10,000 men were now in Framlingham to support her cause, camped in and around a small town of usually only 600 people.

At this time the Duke of Northumberland's army had left London and was marching to confront Lady Mary, via Cambridge.

|

|

Queen Mary

|

|

blank |

Mary was proclaimed Queen on July 19th 1553 by the Privy Council in London. With Northumberland's army out of London they could see that she had widespread support, and admitted they had been in error. The Lord Mayor and Aldermen of the city proclaimed Mary the true Queen along with the Duke of Arundel, by public proclamation. They now put out a reward for the capture of Northumberland. Northumberland's army was now refusing to proceed past St Edmundsbury because of the size of the army waiting for them at Framlingham. Many were deserting Queen Jane's cause.

The Duke of Suffolk was now vigorously turning against Jane, despite the fact that she was his daughter, and even tore down her banner with his own hands, said she was no longer queen, and ordered his men to disarm.

The population of London went wild with joy at this news.

On 20th July many of the Council, including Arundel, had ridden to Framlingham to pledge allegiance to Mary, and to beg for forgiveness for ever supporting Jane. Sir William Waldegrave was there from Bury in her support, and even protestants like Edward Withipoll of Ipswich were now in Framlingham to pay court. By now, Northumberland's army had reached Bury, and the Framlingham army was mustered to attack them. In the event Northumberland retreated, and a smaller band went in pursuit of him and any supporters they could find.

On 24th July Queen Mary left Framlingham to proceed with a large company to London. They took the road to Saxmundham, turned towards Parham, and headed to Ipswich. The Queen stayed overnight at Humphrey Wingfield's house in Tacket Street. After a day's rest, they rode to Colchester. Over the next few days they travelled to Boreham, Ingatestone Hall, and on to Havering, where Lady Elizabeth, Mary's sister, came to pledge loyalty. Elizabeth was only 17, and must have felt in some danger as she was just as Protestant as Edward VI had been.

Mary entered London as Queen on August 3rd, 1553. On 10th August she released some of the prisoners held in the Tower who held Catholic beliefs, notably Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, and Stephen Gardiner, the Bury born former Bishop of Winchester. Thomas Howard was made Lord Marshal, and by the end of August, he had presided over the trial and execution of John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland.

Queen Mary would reign for only five years until 17th November 1558. She came to the throne on a wave of popular support, but would leave it almost universally despised. She now set about a Catholic revival, while promising freedom of worship.

The First Statute of Repeal was passed by Parliament which repealed all of Edward VI's protestant legislation.

Within days the churches in the City of London had alters and crucifixes installed. Nicholas Ridley was thrown into the Tower, and Stephen Gardiner replaced John Ponet as Bishop of Winchester. Stephen Gardiner also became her Lord Chancellor. He was a devout Catholic, and was the son of John Gardiner, a Bury St Edmunds Clothmaker. Like Nicholas Bacon, also of Bury origins, he probably helped the town by minimising the impact of the dissolution of the guilds, and helped the feoffees.

Queen Mary appointed William Cordell of Melford Hall as Solicitor General and a member of her Privy Council. William Cordell had already risen to dizzy heights from his origins at Melford, but would go on to do better. His father is believed to be a John Cordell, who was Steward for the Clopton family at Kentwell Hall in Melford. Such was his new position that the Queen would be prepared to grant him the freehold of Melford Hall in 1554, a property which he had previously leased from the crown.

Sir William Drury of Hawstead became a Privy Councillor to Queen Mary some time in the autumn and was one of those charged to survey the ordnance and stores. Drury augmented his inheritance of seven Suffolk manors by grant, marriage and purchase. Two of his acquisitions, Lawshall and Whepstead, both in Suffolk, were confirmed to him by Mary to hold in chief on his surrender of an annuity of 100 marks awarded him in Nov 1553 for his services during the succession crisis.

Many prominent protestants now left the country, all within a matter of three weeks. In a few more weeks many prominent men throughout the land were replaced in public offices by Catholics. Queen Mary replaced all of the religious provisions of both Henry VII and Edward VI's reign. Churches were ordered to re-equip for Catholic worship and the old services reinstated.

Queen Mary's sister, Elizabeth was noticeably protestant and tried to avoid attending Mass and Mary became intensely suspicious of her.

By November, Mary wanted to marry Philip of Spain amidst general public protest. Parliament had recommended an English Lord, the Duke of Devon, but the queen favoured the suggestion of the Emperor Charles V, that she should marry his son Philip, the heir to the throne of Spain.

A key player in Queen Mary's bid to restore Catholicism in England, Sir William Drury was ordered to search the house of Thomas Pooley of Icklingham who was leading a Protestant revolt against the Queen's proposed marriage to King Felipe of Spain.

|

|

1554

|

In January, Sir Thomas Wyatt raised an army of 4,000 men in Kent in an attempt to stop the Spanish marriage, and in protest against the removal of the reformed faith. They reached London where they met the Duke of Norfolk defending the city. Many of Norfolk's own troops went over to Wyatt's side. Queen Mary herself turned out to rally Londoners to her cause, and confronted the rebels at Charing Cross, where Wyatt and many of his supporters were arrested. Within a few weeks Wyatt's protest had failed.

Mary was now convinced that a crack down was needed, and hundreds of Wyatt's followers were hanged. In February Lady Jane Grey was executed along with her husband, Guilford Dudley, and the Duke of Suffolk, Henry Grey, her father. The Queen's sister, Lady Elizabeth was sent to the tower under suspicion of supporting this revolt. She was there eight weeks in fear of execution. Sir Henry Bedingfield then took her to Woodstock Park under lock and key for a year.

By April, Thomas Cranmer, (previously Archbishop of Canterbury), Nicholas Ridley, (lately Bishop of London), and Edward Latimer were under arrest, along with other lesser clergy, like the Dean of Hadleigh, who resisted the introduction of the Mass.

Queen Mary issued injunctions that removed the newly married priests from office.

In August Queen Mary married Philip, "the Prudent", of Spain in Winchester Cathedral. He would become King of Spain in two years time. The marriage ceremony was performed by Stephen Gardiner the Bury St Edmunds born Bishop of Winchester.

After her marriage the Heresy Laws were revived, and the Second Statute of Repeal aimed to undo Henry VIII's anti-papal legislation. The country was to return to the ways of 1529, but it was too late to undo the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

|

|

Melford Hall today

|

|

blank |

The estate at Melford Hall had belonged to the Abbey of St Edmunds until seized by the crown in 1539 as part of the Dissolution. Henry VIII had leased Melford Hall and its estate to William Cordell since the 1540's. Edward VI had given the freehold to his sister Mary, who was now Queen Mary. She decided to grant William Cordell the freehold in 1554 in place of his leases. The Melford estate was to be associated with the Cordell family for many years.

William Cordell added some features to Melford Hall, although it was already a grand building, having been rebuilt by Abbot Reeve, earler in the 16th century. However, there was now a fashion for a Banqueting House, reserved for the enjoyment of a "banket" of sweets, fruits, and confectionary of every conceivable kind. Some houses had such a room added on the roof, but at Melford it was added in the garden as a separate building, during the 1550's, by William Cordell.

|

|

Redgrave Hall

|

|

blank |

At Redgrave, Sir Nicholas Bacon had finished building Redgrave Hall as his main Suffolk residence. It cost him £1,253. Bacon had been a solicitor, but in 1540 he became solicitor to the Court of Augmentations. This involved him in the disposal of lands taken from the Church in the Dissolution of the Monasteries. He made enough money to buy Redgrave in 1545. He removed the old Grange of the monks, and used his position to plunder materials from the newly redundant church buildings, such as St Saviour's hospital at Bury, and others. In 1547 he became Attorney of the Court of Wards and Liveries which gave him another source of profit.

Although he was a Protestant, he was useful to Queen Mary, and he kept his religious convictions to himself throughout her reign.

Redgrave house was rebuilt in 1763 in a more modern style, but demolished in 1946.

|

|

1555

|

By 1555 the second Parliament under Mary had passed laws which restored the Roman Catholic Church officially in England. All the laws which had been passed to remove the authority of the Pope were now repealed. But of more significance was the decision to restore the medieval penalties for so-called heretics who continued to oppose these changes.

Queen Mary's Lord Chancellor was Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester and a Bury man who helped the town retain or re-acquire monastic lands seized directly by the crown. Gardiner had overseen the laws which re-introduced burning at the stake for protestants.

This change was to result in Queen Mary being remembered as Bloody Mary for her persecution of Protestants. The burning of heretic Protestants now got underway. A church court could pass this sentence, and the victim was then handed to civil authorities to carry out the sentence.

|

|

First Suffolk Martyr

|

|

blank |

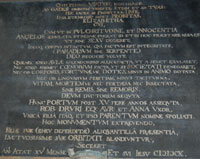

In February Dr Rowland Taylor, the Dean of Hadleigh, was burned to death on Aldham Common. He was the first of the Marian Martys, (as they are known), to die in Suffolk. Nationally, over 300 people would die in this manner before Queen Mary herself died. Twelve were martyred in Bury, and their memorial stands in the Great Churchyard. About 30 Suffolk people were martyred in total.

The martyrs were not just church officials, or prominent citizens. For example, James Abbes, a shoemaker from Stoke by Nayland, was burned at Bury in August, 1555.

In September 1555, Thomas Cobbe, a butcher from Haverhill, suffered martyrdom at the stake at Thetford for his Protestant faith. He had denied transubstantiation and said that Baptism was not a sacrament.

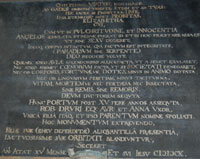

By December Stephen Gardiner, the Chancellor and Bishop, was dead. Few of the common people would mourn him. He had risen from being the son of a cloth merchant in Bury St Edmunds to being Bishop of Winchester under Henry VIII, imprisoned in the Tower for opposing the Protestant reforms of Edward VI, and reinstated as Bishop of Winchester and made Lord Chancellor of England by Queen Mary. He had been the architect of Henry VIII's Six Articles, which had resulted in the deaths of high ranking Protestants, but under Mary these laws were extended to all Protestants, both high and low born. His tomb lies in Winchester Cathedral.

An Act of Parliament was passed to give parishes the responsibility to maintain the roads in their areas. The Highway Act of 1555 placed responsibility upon the parish highway surveyor, who was unpaid, but probably did his best with scarce resources.

|

|

1556

|

In February 1556, Latimer and Ridley were burned at the stake in Oxford. Thomas Cranmer followed them shortly afterwards.

Women could also suffer this fate. For example at Ipswich, in February 1556, Joan Trunchfield, a shoemaker's wife, and Anne Potton, a beer maker's wife, were both burned to death on the Cornhill for refusing to renounce the Protestant religion.

Philip of Spain now became King Philip of Spain when Charles V abdicated.

|

|

1557

|

In June, war was declared on France. Philip, now King of Spain, had finally drawn his wife, Mary, and England, into his father's war with France. One outcome of this was that in December, the English ruled town of Calais was overrun by the French army. This was England's only safe base in France, and was a bitter strategic and emotional blow. Calais was a symbol of the triumphs of the Black Prince and Henry V.

Despite war and hardship from poor harvests, the burning of Protestants continued. At St Edmundsbury, three people were burned in June, 1557. They were Roger Barnard, a labourer from Framsden, Adam Foster, a tailor from Mendlesham, and Robert Lawson, a linen weaver from Bedfield.

In November, Thomas Spurdance, described as a royal servant, from Crowfield, was also burned at Bury.

In Bury, William Tassell conveyed the Angel and the Castle Inns on the site of today's Angel Hotel to the Guildhall Feoffees to provide on income for various charitable purposes in the town. Specifically his deed stated that the income was to be used for the maintenance of the two parish churches, St James's and St Mary's, for setting forth soldiers, and for the relief of the people of the town. The Feoffees kept it until 1582, then re-acquired it in 1606. It was finally sold off in 1917 to raise funds.

William Cordell of Melford Hall had been the Queen's Solicitor General since 1553. In 1557 she made him Sir William Cordell, and gave him the post of Master of the Rolls.

|

|

1558

|

On 11th January, 1558, Sir William Drury of Hawstead died. By now, his eldest son, Robert, had died, and the estates passed to Robert's son, William. William was still a minor, aged 7, so the will made provision for Sir William's wife to hold the estates for 10 to 13 years until young William reached 21 years old. In this will there was no mention of Hawstead Place. Evidently it was still called 'Talmage, otherwise called Buckenham's', as referred to in the will.

John Crofts of Little Saxham Hall also died in January 1558 and was buried at West Stow, which had remained the Crofts' hunting lodge ever since the move to Little Saxham in 1531. West Stow must have remained an important part of Croft's life, despite living mainly at Saxham.

Croft's son Edmund, born 1520, was his son and heir. At the age of 17 he had married Elizabeth Kitson, or Kytson, who was the daughter of Sir Thomas Kytson, the builder of Hengrave Hall, who died in 1540. Edmund only survived his father by three weeks, and he also died in January or February 1558. Thomas Crofts now inherited the Little Saxham estate. He was born in 1538 and had 12 children by his wife Susan. He became Sheriff of Suffolk in 1595 and outlived his wife by 8 years, dying in 1612.

In August 1558 there were more burnings at Bury St Edmunds. All four of the victims were from Stoke by Nayland, Robert Miles, a shearman, Alexander Lane, a wheelwright, John Cooke, the sawyer, and James Ashley.

Three more Protestants were killed at Bury in November, only days before Bloody Mary herself was to die in her bed. They were Philip Umfreye, a tailor from Onehouse, and from Stradishall, John Davye, a shearman, and Henry Davye, a carpenter.

It is noticeable that nobody from the town of Bury itself was burned as a Protestant heretic. While Hadleigh had a strong Protestant movement, as had Ipswich, it was the Stour Valley and central Suffolk where anti-Catholic feeling was strongest at this time. Haverhill and Stradishall had their martyrs while much larger Bury did not.

Within a month or two of her marriage to Philip of Spain, there had been announcements that the Queen was pregnant. No child was born, and there were further such announcements over the short years of her reign. By 1558 it was instead believed that the Queen was suffering from a fatal dropsy, which today may have been diagnosed as ovarian cancer. Parliament had always refused to name Philip as a successor King of England, and so in November, as Mary lay dying, she named Elizabeth as her successor. Philip, now King of Flanders, as well as Spain, tried to maintain his hold on England.

Mary had come to the throne on a wave of popular support, but she died hated, on 17th November. Vast cheering crowds greeted Elizabeth to London. Queen Elizabeth I came to the throne and reigned for forty-four years.

Sir Nicholas Bacon was by now an extremely wealthy landowner, mainly acquired through holding the office of Solicitor to the Court of Augmentations from 1537 to 1546. He was made Lord Keeper of the Great Seal in 1558. Bacon owned the Manor of Redgrave and retained links with Bury. His father had been a yeoman at Drinkstone.

|

|

Queen Elizabeth I

|

|

1559

|

Queen Elizabeth I was crowned in the grandest style in 1559. She had two hurdles to overcome, both assumptions in peoples minds. These were that no woman could be as good a ruler as a man, and that no ruler could be as great as Henry VIII. Following the reign of Bloody Mary, John Knox had even written pamphlets to say that a woman could never be a fit ruler.

Nothing daunted, Queen Elizabeth immediately began to once again dismantle the trappings of catholicism in the churches and re-introduce protestant forms of service.

The Act of Supremacy of 1559 once again made the monarch head of the English church. This has been called the Third Reformation of the English church, counting Henry's as the first and Edward VI's as the second. The Queen made herself Supreme Governor of the Church of England and decreed that her coat of arms should be placed in every church.

The Act of Uniformity authorised a new English Prayer Book, and levied a shilling fine on anyone not attending Sunday church of the new Protestant type. This prayer book was not quite so strict about the doctrine of transubstantiation and a concession was made which allowed crucifixes and some furnishings in church. Some vestments could be worn by priests and the sign of the cross could be made at Baptism. This was protestantism with enough of the old ways retained to appease those who missed the old religion. While this may have helped reconcile the ordinary folk to the new church, it satisfied neither the strong Catholic or the new Puritans.

Tobacco was introduced from the new world.

|

|

1560

|

On 14th February, 1560, Queen Elizabeth in consideration of £412 19s 4d. paid by John Eyer, Esq., granted him (inter al) "All that the site, circuit and precinct of the late dissolved Monastery of Bury, otherwise called "Bury St Edmunds" amongst the specified lands and buildings being the Dorter Court, the Garners, the Abbot's Stables, the Gate House, the Great Court, the Pallaies Garden, the Lecture Yard, Bradfield Hall, the Pond Yard and the Vine." The ashlars were sold by the cartload for building material, but most of it had probably already gone. John Eyer already had rights to monastic rents in many parts of Norfolk and Suffolk which he had obtained under Henry VIII in 1544. He now lived for many years in the Abbey precincts in a grand mansion. It is believed that he commissioned a painted copy of the stained glass window in the Cellarer's old Quarters within the abbey, and this copy survives in Moyse's Hall Museum today.

|

|

1561

|

By 1561 Queen Elizabeth had again fully changed the appearance of English churches and services back to protestantism. Many noble families were caught up in the changes of the last twenty years, coming in and out of favour as the state religion changed. A number of important Suffolk families kept the Roman Catholic faith, the most notable being the Howards who were Dukes of Norfolk. Others were the Bedingfields, the Sulyards of Haughley Park and the Rokewoods of Euston and Stanningfield. Sir Thomas Cornwallis had been controller of the household to Queen Mary, but now retired to Brome in Suffolk.

At Hengrave Hall, Margaret Kytson died, to be succeeded by her son, Thomas Kytson, the younger. Thomas was a friend of the Duke of Norfolk, and at this time also came under suspicion for this association.

On the other hand there were even more families of a Puritan persuasion, a faith that continued to grow. At Ipswich the Queen was offended when the extreme protestant clergy refused to wear the surplice, which she had just re-introduced, as part of her compromise reforms.

Sir Robert Jermyn of Rushbrook Hall had the gift of ten livings locally, and he appointed puritan sympathisers when a vacancy arose. These included Horringer, Bradfield, Stanton and Welnetham.

Similarly the puritan Sir John Higham of Barrow had four benefices in his gift. Other Puritan gentry locally with power over livings included Sir Nicholas Bacon junior of Redgrave, and Sir William Spring of Pakenham.

|

|

Sir Nicholas Bacon

|

|

1562

|

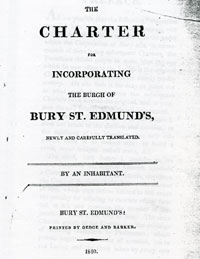

Lord Keeper of the Queen's Privy Seal Bacon wrote to the Feoffees of Bury St Edmunds to say that he would "be glad and willing to travail as I may conveniently" to help them get a charter of incorporation for the town of Bury St Edmunds. However, he warned them that "there is an opinon received among men of wisdom and understanding, that the number of incorporations already granted and established within this realm are so many, and it is not meet nor convenient to have that number increased with any more." His letter was addressed to Sir Clement Higham, Sir Ambrose Jermyn, Henry Payne and John Holt.

Nicholas Bacon was a barrister who had connections with Bury and became Solicitor to the Court of Augmentations, acquiring much monastic land, including the manor of Redgrave, in the process.

There were still legal issues outstanding since the dissolution and annexation of monastic and "superstitious" property begun by Henry VIII. In the Council yearbook for 1896/97, which lists the charities of the town of Bury St Edmunds, one such disputed property was the Guildhall itself. This deed appears to have been necessary to settle ownership once and for all.

"By letters patent, bearing date 6th July, 4 Elizabeth, (ie 1562), the following properties, viz, the Guildhall, a messuage or tenement and Grange, in Eastgate, then lately used as the Grammar School, and the Manor of Bretts in Hepworth, which amongst other property, were alleged to have been concealed from the Crown, were granted to the Feoffees of the Town Lands for the common profit and benefit of the Burgesses of the Town."

Part of Queen Elizabeth's church reforms included the licensing of preachers. Only those ordained ministers trusted to preach the official doctrine would be given a license. Any minister who was unlicensed could only read out a pre-written sermon. A selection of acceptable sermons was published in 1562, entitled "Certain Sermons or Homilies, appointed to be read in Churches." This book was reprinted many times and was still in use in 1683, when it was re-issued under Charles II.

|

|

Kentwell Hall 2005

|

|

1563

|

Tolls of Bury's markets and fairs were leased by the crown for 21 years to Thomas Andrews.

Around 1563 the Clopton's mansion at Melford, now called Kentwell Hall, was completed. Unlike Melford Hall, which today looks very different to the 16th century building, Kentwell remains today looking the very much same as it did at this time.

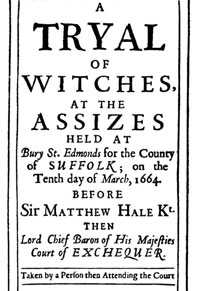

The first Witchcraft Act came into force in England. English law now accepted witchcraft as a fact, and it was made a crime to be found guilty of witchcraft. The Witchcraft Acts were not abolished until 1763.

|

1564

|

In 1564 Bartholomew Brokesby gave "several houses" to the poor, which stood on Crown Street, backing on to the churchyard, a little distance from the west end of St Mary's church. Almshouses apparently stood on this site until taken down in 1813, and replaced by ten in Westgate Street. The source for this is a plaque erected on College Square in 1909, where several of these old endowments were consolidated into this new development by the Guildhall Feoffees.

|

|

1565

|

Bury St Edmunds was divided into the two parishes of St Mary's and St James'. Each parish had a minister, who was under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Norwich, and a preacher, chosen by the congregation. In Bury at this time the congregations also claimed the right to appoint their own minister, which could become a point of conflict with the bishop. In 1565, one of the town preachers was George Withers, a Protestant whose views were more reformist than the English Reformation allowed. Withers caused controversy when he refused to wear a cornered clerical cap.

|

|

|

Wildcat extinct in Suffolk by 1590

|

|

1566

|

There had been various Acts of Parliament passed to control "vermin" species, but the strongest legislation came in 1566, for the "Preservation of Grayne". Harsh winters and poor harvests characterised the second half of the 16th century, and the government wanted to preserve as much food as possible for the human population. All parishes had to impose a levy upon landowners and farmers to provide a vermin fund. This fund was used to make payments to parishioners who showed evidence of the destruction of any of a long list of "pests". There was a price fixed for the deaths of stoat, weasel, polecat, pine marten, badger, fox and wildcat, as well as for the rats and mice which we might expect. Hedgehogs were on the list for stealing eggs and moles for damaging pastures. These payments continued for 300 years, until repealed in 1863. By the end of the 16th century the wildcat would become extinct in East Anglia. Pine martens clung on until the early 19th century, while polecats were eradicated by the end of the 19th century.

Suffolk Broadcloth was by now old fashioned. It was heavy and dark. People now wanted the New draperies, which were lighter, more colourful and cheaper than traditional woollens and worsteds. In 1566 the first "Strangers", as they were called, arrived in Norwich. These were Protestant refugees from the Netherlands, which were now under Spanish rule, and being "converted" to the Roman Catholic religion. They brought with them the knowledge and equipment to produce the New Draperies. In 1568, another refugee colony had started in Colchester. These two centres of Norwich and Colchester would become formidable competition to the established Suffolk trade, including to Bury St Edmunds, Lavenham, and the rest.

|

|

1567

|

The manor of Ousden had been owned by the Waldegrave family since the beginning of the 15th century. In 1567 it was sold to the Moseley family, who would own the manor until 1800. During the late Tudor period the family built the first Ousden Hall. Two Georgian style wings would be added in the 18th century. Memorials to the Moseley family may be seen in Ousden church, the most unusual incorporating a carved skeleton depicting Laititia Moseley, who died in 1619.

According to the "History of St Mary's Church, Troston", by Clive Paine, that church had a bell that was originally cast by Stevan Tonni of Bury, in 1567. Although all the bells here were recast in 1868, the original inscriptions were retained. We believe that Tonni did not start his foundry until 1570, so this may be a transcription error for 1576.

|

|

Lavenham frozen in time

|

|

1568

|

Sir Edward Coke reported that three Suffolk Gentlemen refused to attend church. These Catholic recusants, as they were called, were Messrs. Cornwallis of Brome, Beddingfield of Denham, and Silyarde of Haughley.

Meanwhile another Lay Subsidy or tax was demanded from those worth more than £1 a year from lands, or £3 or more in goods. The return for Suffolk has been published as Volume XII of the Suffolk Green Books. Although Betterton and Dymond noted that this tax was widely avoided, they suggest that by this time Lavenham had sunk in wealth to only a position of eighth in Babergh Hundred and 49th in wealth in the whole county of Suffolk. Lavenham's great heyday was over, and it was never to return. This fact alone seems to be the reason that Lavenham appears to be frozen in time with its early Tudor timber framed buildings surviving to the present day. Lavenham never again became rich enough to replace its old worn out and unfashionable buildings as usually happened every century in other more prosperous towns.

Those families who had become wealthy from the cloth trade a half century earlier, had forsaken Lavenham industry and taken their wealth away to become "Gentlemen". The Spring daughters married into the nobility. Margaret Spring married Sir Thomas Jermyn of Rushbrooke. A cousin also called Margaret Spring married Aubrey de Vere, second son of the 15th Earl of Oxford. They moved their family seat out to Pakenham. John Spring had married into the Waldegrave family at Bures and had been knighted by the boy king Edward VI in 1547.

Other wealthy clothiers who had left the Lavenham trade to become gentry were Robert Crytofte, John Grome and Thomas Rysby. Thomas Rysby died in 1568, but he had already settled his family into Thorpe Morieux as Lords of the Manor.

|

|

1569

|

In July another popular rebellion broke out at Lavenham. A weaver called John Porter was a local ringleader and his grievance was against the newly rich merchants. Suffolk dyed cloth was no longer wanted on the continent and although some big clothiers were still rich, there was no longer the guaranteed work for the small weavers and spinners of fifty years before.

The Feoffees at Bury St Edmunds had to find money to buy back from the Crown some further property recently confiscated on the grounds that it had been unlawfully concealed from the confiscations of 1545. These included the Guildhall in Guildhall Street and the Guildhall of the Guild of St Thomas à Becket in Eastgate Street. This latter building, possibly today called Ancient House, was let rent free to the Governors of the Grammar School.

|

|

Foxe's Book of Martyrs

|

|

1570

|

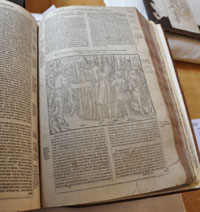

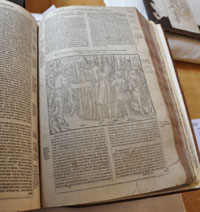

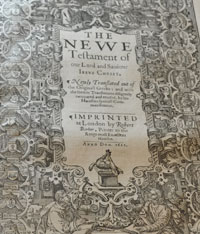

Religious questions were the main intellectual topic of the day. This is the second edition of John Foxe's Book of Martyrs which was printed in 1570 by Suffolk man, John Daye. (The first edition came out in 1563.) This particular volume would be preserved in St James library and would be one of the largest volumes that the library possessed. Indeed, at this time it was the largest publishing project ever carried out. The 1570 edition was 2,300 pages long, with major corrections and additions to the first edition. It was so well received by the English church that it was to be placed in every church in the land, alongside the Bishops' Bible. It deeply offended Catholic sensibilities, and would become the main tract of anti-catholic feeling for decades afterwards.

Although it covered all the early martyrs, its intent was to concentrate upon the sufferings of English Protestants in the Tudor period under Queen Mary. This page shows the death of Roland Taylor, Rector of Hadleigh and Archdeacon of Bury, who was burnt to death at Hadleigh in 1555. This copy would be owned by Robert Plummer, a Barber Surgeon of Bury, who would donate it to St James's Library in 1680. Further editions were printed in 1576 and 1583.

By 1570 the Guildhall Feoffees were repairing town gates and bridges and carrying out many duties which would otherwise have fallen to the Town Corporation if one had existed. They even provided a town pillory. They seem to have been known as the Alderman, Dye and brethren of Candlemas Guild into the 1570's, despite the Guild's dissolution in 1545.

In 1570 the William Barnaby alms houses were on the site of Jankyn Smyth's College of Jesus founded as a residence for the parish priests of St Mary's and St James'. In 1570 they were owned by William Barnaby who conveyed them to the Feoffees. Barnaby himself lived in the manor house at Great Saxham. After the reformation men of good will who would previously have left money to the church or for "superstitious" purposes, now left it to help the poor.

The Feoffees even felt it necessary to finance a Town Preacher in Bury, and Puritan ideas led to a rise in religious discussion groups, and the clergy were as likely to be criticised as anyone else, for not being Godly enough. These ideas would gain more and more ground to the middle of the next century.

The Pope, Pious V, increased the pressure on England by issuing a Bull which excommunicated and deposed Queen Elizabeth I. This declaration, "Regnans in Excelsis", in effect meant that the Pope declared war on England. After this event Catholicism was regarded as treason in England, and penalties against them were more rigidly enforced.

Those Catholics who had hitherto quietly attended church as non-communicants or schismatics, (meaning that they followed protestant worship but were catholic in their hearts), were now faced with either defying the Pope or joining the new church fully. Hard choices had to be made, both by Catholics, and by the Queen, who had a potential Fifth Column of recusants in her midst.

The manor of Mildenhall had been seized by the Crown at the time of the dissolution of St Edmund's Abbey. It had subsequently been leased out. In 1570 a new 30 year lease was sold to Sir Nicholas Bacon, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal. After the death of Sir Nicholas in 1579 the lease passed to Henry North.

|

|

1571

|

In 1571 William Drury reached the age of 21. He was heir to the Drury estates at Hawstead, including many other manors in Suffolk. It is suggested by Sir John Cullum, in his History of Hawstead, that William was responsible for transforming the old Bokenham's Hall into a modern mansion. "It was this Sir William Drury, I apprehend, who rebuilt, or greatly repaired, Hawstead House, afterwards called Hawstead Place, or The Place." By 1578, the Place was suitable to be visited by Queen Elizabeth I.

|

|

1572

|

The Feoffees set up an almshouse at St Peter's Hospital, which later became a House of Correction to handle penniless troublemakers. This was the hospital which was founded by Abbot Anselm for infirm priests, and stood in Out Risbygate opposite the site of today's West Suffolk College. Later it moved to Bridewell Lane.

The 4th Duke of Norfolk, of the Howard family, like his predecessors, had kept the Roman Catholic faith. In 1571 he had become involved in the plot to replace Queen Elizabeth by Mary, Queen of Scots. He was put in the Tower and executed in 1572. Up to this point he had held tremendous power in both Norfolk and Suffolk, appointing JP's and getting involved in nominating MP's as well. His execution gave other lesser gentry of Suffolk the freedom to get much more involved in public life in the county. The Duke of Suffolk had already lost much of his hold over Suffolk when the Liberty of Eye was returned to the Crown in 1538.

At the other end of the religious spectrum were the more extreme protestants. Both Catholics and extreme Protestants were out of favour with the established church and state because of their refusal to conform to the established modes of worship and thought. In 1572 the more Protestant elements in Bury St Edmunds brought in a new Town Preacher called John Handson. Handson quickly came to the attention of the establishment for refusing to wear a surplice, not just during normal services, but even during holy communion.

|

|

1573

|

Despite his lack of help with incorporation in 1562, Sir Nicholas Bacon, who had been one of the Feoffees for years, was elected Alderman at Bury St Edmunds. Bacon was Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, a Bury man who was also an important national figure.