The Great Charter

The Great Charter

Quick links on this page

Mabilla of Bury 1230

Franciscans- Friars Lane 1238

Franciscans in danger 1257

Guild of Youth riots 1264

Abbey gets Haberden 1281

Town gets Alderman 1292

Shire Court moves North 1301

The Great Famine 1315

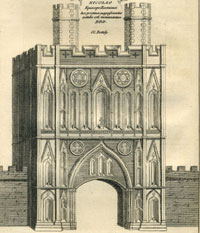

Abbey Gate destroyed 1327

The Black Death 1348

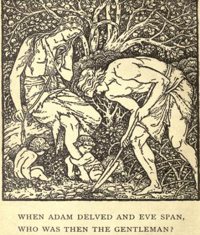

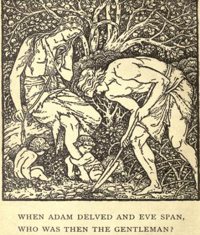

The Peasants Revolt 1381

St Mary's Tower 1400

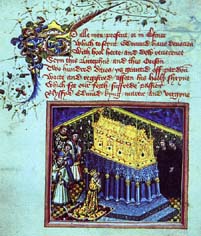

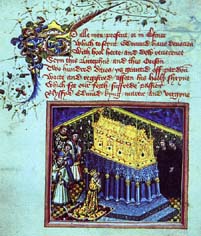

John of Lydgate 1420

Duke of Gloucester dies 1447

Great abbey fire 1465

Feoffees' beginnings 1472

Rushbrooke Hall started 1500

Martin Luther's Protests 1517

Henry VIII Head of Church 1535

Foot of Page 1539

|

The

Middle Ages

St Edmundsbury From

1216 to 1539

Pre

1216

|

Please click here to look back at events in and prior to 1216.

|

|

1216

|

After the traumatic events of King John's reign, his son Henry III came to the throne in October at the age of nine. The Civil War which followed John's renunciation of his Magna Carta ended as the barons rallied to Henry. As he was under age his throne was administered by a group of Barons led by William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke and Hubert de Burgh, as well as Archbishop Langton. They enhanced the role of the Great Council and adopted Magna Carta principles, re-issuing it in November 1216 with 42 clauses.

The French, however, were still in the country, and determined to take over under Prince Louis, who had declared himself king.

The year 1216 is sometimes taken to be the end of the Anglo-Norman, or Early Medieval period, and the start of the Middle Ages. The Middle Ages can be reckoned to last until 1348, when the era becomes known as Late Medieval, 1348-1485. The story of Suffolk in the thirteenth century was to be one of growth and prosperity.

|

|

1217

|

Magna Carta, or The Great Charter was again modified and reissued along with a Charter of the Forest. Roger of Wendover mistakenly attributed this version to King John and 1215.

Orford Castle was surrendered to Prince Louis of France, who had launched an expedition into England, and attacked several towns around the south east. There is no record of him attacking Bury St Edmunds, but it has been suggested that he did come to Bury, and made off with the relics of St Edmund, returning to France with his remains. This is the thesis of Father Houghton's book on St Edmund, but this event has no evidence to support it in records of the abbey.

The Bury Chronicle recorded that many Frenchmen were killed in the battle at Lincoln on 19th June. Also that on 24th August the French fleet arriving in the Thames estuary to help Louis were sunk. Louis returned to France and about 8th September, "the great gift of peace was granted once more after two and a half years war".

Robert of Graveley had been the Sacrist of St Edmund's since the demise of William of Diss. Late in 1217 he was elected to the post of Abbot of Thorney. Robert was recorded in the 1270s Gesta Sacristarium as as efficient and active Sacrist. He had bought the Abbey's Vineyard and enclosed it with stone walls for the "comfort of the infirm and those who had been bled." This area is still known as the Vinefields in the present day. He also provided new rafters for the abbey roof, and placed a decorated canopy over the shrine of St Edmund. The account of the election of the Abbot Hugh called "Electio Hugonis", may well have been written a year or two after Robert left Bury, for it is heavily biassed against him. Robert had been the chief contender with Hugh for the post of Abbot during the election of 1213.

|

|

1219

|

A great school of history was established at St Albans when Roger of Wendover began his History of the World. His account of the struggle of the Barons with King John is the only known account of the involvement of Bury St Edmunds in the story.

|

|

Chapter House c1220 visualisation

|

|

1220

|

This visualisation of the building of the Chapter House at St Edmund's Abbey in about 1220 was made by Bob Marshall, now a digital illustrator at English Heritage.

|

|

1225

|

Henry III issued his final version of Magna Carta and its main principles remain in law today, and were only slightly amended in 1297. This is the final version which has become so important today, with only minor changes in 1297. It still stands in the law books today as Chapter 25, Edward I. When Henry III came of age he tried to regain control from the Great Council but he was regarded as extravagant and somewhat incompetent.

The Bury Chronicle notes that the Order of the Friars minor (Franciscans) and the Order of the Preaching Friars (Dominicans) established themselves for the first time in England. These orders would come to be a challenge to the established monastic orders in future years, both in their spiritual authority and in their claims to the moral leadership of the people.

|

|

1226

|

The Bishop of Ely obtained a charter to set up a market on the major road from Bury to Ipswich in the corner of his manor of Barking. He created Needham Market as a settlement around it. Unlike Lakenheath in 1201, this market was safely outside the Liberty of St Edmund.

|

|

1227

|

In 1227 King Henry III confirmed a charter to Richard Argentein for a fair to be held in his manor of Newmarket for three days every year in September. This has been taken to be the origin of Newmarket as a town, but it seems likely that a market had grown up in this location some years before this date. It was in a corner of the vill of Exning, but situated conveniently to serve travellers on the old Icknield Way. Although the Icknield Way was probably a series of tracks, these had to converge with the Norwich and Bury roads at this location to pass conveniently through the Devil's Dyke earthwork, lying to the south west of the settlement.

|

|

1229

|

Hugh de Northwold, abbot at Bury was consecrated Bishop of Ely. His place as abbot was taken by Richard de Insula, the abbot at Burton. He ruled from 1229 to 1233.

|

|

1230

|

King Henry III crossed into Brittany with an army.

|

|

Mabilla by Sybil Andrews

|

|

1231

|

At some period in the early thirteenth century, Mabel of Bury St Edmunds became one of the most famous needlewomen in Europe. Little is known about Mabilla or Mabel of Bury St Edmunds except that her work is referred to by name in the Royal Wardrobe accounts of the court of Henry III. We believe that the type of needlework for which she was famous was called Opus Anglicanum or English work. It was used for ecclesiastical vestments, altar frontals and other ceremonial purposes and was thus richly worked and expensive. The work was sent to other ecclesiastical houses here and abroad as well as to foreign royal courts. Mabel was so highly regarded that she became a King's pensioner, having made many commissions for Henry III himself. She would die in 1244. Opus Anglicanum was made by both men and women and was highly prized. Today her name is continued by the Mabilla Group who had their headquarters at the Manor House Museum while it was extant, and who supported the textile collections of the Borough.

|

|

1232

|

The Earl of Kent was imprisoned by the king. His wife fled for sanctuary to St Edmund's, and she remained there in safety until peace was made with the king in 1234. The king had ordered her capture, but in deference to the Liberty of St Edmund, respected the sanctuary which it could offer to fugitives.

|

|

1233

|

Abbot Richard died abroad on his way to visit the pope. Henry the Prior at Bury was elected to replace him.

|

|

1235

|

Roger of Wendover died at St Albans, having continued to write his History of the World up to the end. The task was taken over by Matthew Paris, who re-wrote much of the text with his own embellishments in the years up to 1259, when he himself died. This is of interest to the student of the history of Bury St Edmunds because it is these authors on whom we rely for the story of the Barons meeting in Bury to swear to enforce Magna Carta upon King John.

There is a record of the King giving deer from his park at Hundon to Sir Ralph de Wancey, lord of the manor of Depden.

|

|

1238

|

The Franciscans first came to England in 1224 with their establishment at Canterbury. The Benedictines tried to resist these incursions into their territories.

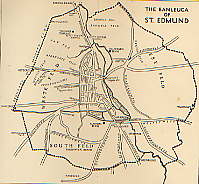

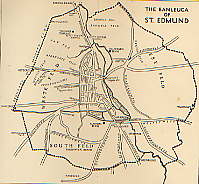

In 1238, Hawisia, Countess of Oxford, granted the Franciscan Friars a site in the town of Bury St Edmunds. Hawisia was the wife of Hugh de Vere, the 4th Earl of Oxford. We do not know where this site was located, but Friars Lane seems to be a possibility. However, the Manor of Maidwater around today's Maynewater Lane area was part of the Honour of Clare and the House of Clare was also a supporter of the Franciscans. Friar's Lane may, or may not, have been located within the manor of Maidwater, but the Franciscans seemed to have set up an unofficial base there. The Abbot challenged this, saying that St Edmund's had a spiritual monopoly within the banleuca.

Otto, the cardinal deacon of Caecere Tulliano, had been made Papal Legate in 1237, and came to England. After the Council of Oxford, he came to Bury, where the Chronicle records that the Preaching Friars appealed to him for somewhere to live within St Edmund's Liberty. After inspecting the boundaries, the

Papal Legate agreed that neither the Friars Minor (the Franciscans) nor the Preaching Friars (the Dominicans) were entitled to settle in Bury St Edmunds.

These events are rather confused in the Chronicle. We are not clear whether there was a dispute about whether the Manor of Maidwater was inside or outside the banleuca, or within the Liberty, or whether it was about the right of the abbey to a spiritual monopoly. Probably, like any legal case, several arguments were advanced at once.

|

|

1239

|

Haverhill's first church was St Marys at Burton End. Before 1200 there was a chapel (also St Marys) in the market place which was officially dedicated by Edmund, Archbishop of York, around 1239. This is part of the present parish church. For the next 300 years there were two churches, less than half a mile apart. Burton End church was called Upper, or Bovetown (ie above town) Church, while the market place church was called Lowerchurch. Eventually in 1551 people decided they could maintain the old church no longer and petitioned King Edward VI to remove it. No trace of it remains.

|

|

1240

|

At Brandon Ferry the Brandon River had been crossed by ferry for centuries, being too deep for a ford. The Bishop of Ely was the landlord and during the 1240s he would have a wooden bridge built to speed up the crossing. Tolls were charged for the use of the bridge. In around 1330 this wooden bridge would be replaced by a stone bridge. As Brandon was on the pilgrim road to Walsingham there were many individuals needing to cross, as well as traders with goods.

|

|

1242

|

In 1242 Henry III held an inquisition to establish the truth about the military knights service owed within the Liberty of St Edmund. One of those knights was Ralph de Wancey of Depden, whose overlord was de Warenne. This inquisition apparently arose because in 1236 the Abbot had avoided giving these details, saying only that he held 40 fees from the king in chief, and 12 others. He would not produce a list of names, saying "in what places and what amounts in each, God knows." The Abbot at Bury St Edmunds at this time was Henry de Rushbrook who took office in 1234.

|

|

1244

|

Mabel, or Mabilla, of Bury St Edmunds, died in November, 1244. She was so famous as a maker of English Work textiles that she had often worked for the king himself. In November, 1244 the royal accounts of Henry III recorded that five shillings was given towards meeting the funeral expenses of Mabilla of Bury St Edmunds.

|

|

Aisled hall house Stansfield

|

|

1245

|

The monks at Bury were greatly impressed when they heard that Queen Eleanor had given birth to a son, and that he was to be named Edmund after the saint and martyr. On 18th January King Henry III wrote to ask the abbot to announce this to his monks.

In 1245 Earl Roger Bigod went on campaign to Lyon. He was the third Bigod to be called Roger. Military conquest was a way to make money, and this applied to the soldiers as well as the commanders. John Algar esquire was a soldier on retainer to Bigod. Algar had a manor at Brockley, and some land at Loddon, but probably doubled his annual income by being ready to fight for Bigod. He would expect to be paid between £10 and £20 a year, as well as getting free board and lodgings when on campaign. Algar was probably also a farmer in his own right, but one willing to risk danger for extra income.

Such a man would emphasise his status wherever he could. He might build a moat around his house, as many did on the Suffolk claylands in the late 12th and 13th centuries. He might keep hawks, or empark part of his land. He might build a new bay on to his timber aisled hall. He could not afford stone building, but could still put on a good show in timber. The aisled hall house shown here is located at Purton Green, in Stansfield. It had two bays when built, in about 1250. This house would have suited a prosperous peasant family or a minor landlord.

Purton Green is one of the lost villages of Suffolk, where generations spent their lives, but which are now just patches of lime and fragments in the plough. It lies on an old road running south from Bury St Edmunds to Clare via Gatesbury's Farm. Today it hardly survives as a path, and access is from the south, requiring a ford crossing, and a 400 yard walk. All that remains of a village is this house. Inside its late medieval walls survives a hall of 1250 – a great rarity. Aisled on both sides, with scissor-braced trusses and a highly ornamental arcade at the low end, it must once have been an important place. The high end of the house dates from a rebuild in about 1600.

The house survives because it was bought as a ruin by the Landmark Trust in 1969, and restored as a holiday let in the 1970s. As with almost all medieval houses, a floor and central chimney stack had later been inserted, but these additions were so derelict that the Landmark Trust felt justified in removing them, to return the hall to its original open state.

|

|

Long Cross penny of Henry III

|

|

1247

|

The Bury Chronicle recorded that there was an alteration to the coinage of England and King Henry granted a newly cut die to St Edmund's. The new die was to be used freely with the right of exchange, just as the king himself used his dies. The new mandate was issued in December. It may be that the town had been left out of this change initially, as there is evidence that two monks, Edmund de Walpole and Thomas, went from Bury with charters to see the barons of the exchequer to prove that the abbot of St Edmund had the right to a mint and exchange.

The change referred to was from the short cross coinage to the long cross, whose arms would reach to the edge of the coin. The earlier Short cross coins were certainly produced at Bury in the reign of Henry III. The aim of this new design was to deter the clipping of silver from the edge of the coinage.

The coin shown here was minted at Bury by a moneyer known as John, and from its design dates to 1248. The inscription reads ION/ONS/EDM/VND, or John of St Edmunds. John was the name of the moneyer, no doubt licensed to make coins in Bury by the Abbot, who himself held the King's mandate to arrange for their production. The obverse shows a portrait of the King and the legend HENRICUS REX TERCI.

Perhaps Haverhill's most famous son was William de Haverhill, who became Treasurer to King Henry III in 1247. He was also a Canon of St Pauls. He was a great success in government and apparently played an outstanding part in keeping the country on an even keel. Little else is known about him.

|

|

1248

|

Abbot Henry of Rushbrook, who had been abbot at St Edmund's since 1234, died in June, 1248. In July Master Edmund de Walpole was elected abbot. He had only been "two years in religion from the day he professed to the day of his election." He must have been an outstanding figure to achieve this, and it had been him who had led the delegation to retain minting rights in the previous year.

Richard fitzGilbert was the 7th Earl of Gloucester and 5th Earl of Hertford, who held the extensive lands in Suffolk and beyond, known as the Honour of Clare. He was a supporter of the mendicant friars and invited the Augustinian friars to come to England, so leading to the founding

of Clare Priory in 1248. He died in 1262.

The Friars Eremites of the Order of St Augustine were also known as the Austin Friars, and Clare Priory was to be their first step into England. Clare became the mother house of the Order in Britain. Until 1124 Clare castle had contained a Benedictine Priory, but in that year it was removed to Stoke by Clare. The Austin Friars got their own premises just outside the castle.

|

|

Guildhall porch with earlier evidence

|

|

1250

|

The Candlemas Guild built a porch on to the Guildhall in Bury. Its remnants can still be seen within the 15th century later improvements.

What was Suffolk society like at this time? This question was addressed by Mark Bailey in his book "Medieval Suffolk", published in 2007. A small group of landlords held the biggest share of the land. Land was the basis of wealth, and even men who made money from trade aspired to buy a country estate. These lands were usually rented to tenants rather than being directly farmed by the owner.

Earls and Barons were on the same level as Bishops and Abbots, and together these were the aristocratic landlords who owned most of the land between them. They would make more than £500 a year from their estates.

Below the aristocracy came the Gentry, owning much less land. They might be Knights or just local landlords.

The rank of landlords below the Aristocracy were the Knights, who might make £100 to £300 a year. A knight would own land worth well over £100 in order to generate this income. Bailey suggested that these were a declining class in this century. Suffolk had around 100 knights in 1200, falling to only 30 by 1300.

Minor local landlords would be doing nicely on £20 to £100 a year.

|

|

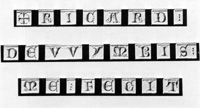

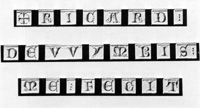

RAN/DVL/FON/SED

|

|

1251

|

From 1251 a slightly different pattern of silver penny was produced. At Bury, one of the moneyers now operating was called Randulf, and the coin illustrated here was minted by him at Bury St Edmunds. No doubt he did not strike it personally, but was probably a gold or silver smith, employing a number of craftsmen in a workshop to make coins. He may well have had another workshop where articles of jewellry would be made.

You can see the reverse of this coin, as well as more coins minted at Bury St Edmunds by clicking here:

Medieval coins minted at Bury

|

|

1252

|

At the death of William de Haverhill in 1252, things began to go wrong for King Henry III, ending six years later in civil war.

The famous chronicler Matthew of St Albans wrote, "Nevermore will mourning Haverhill give birth to any like him."

The Bury Chronicle recorded that the summer was so hot that it killed many people. It also noted that Prior Richard died in October, and was succeeded by Simon de Luton. However, what was noteworthy was that he was selected by the new method of scrutiny. This entailed the abbot and two monks taking a vote orally from each monk. Before this date the Abbot had appointed the Prior, but the convent had now secured a prominent part in his appointment.

|

|

1253

|

According to the Chronicle the sea flooded its shore and submerged many coastal districts.

This event occurred at a time when the average sea level at Great Yarmouth is estimated to have been 4 metres lower than at present. There were many more coastal salt marshes around Suffolk then than there are today. This situation seems to have changed after about 1275, when sea levels seem to have begun to rise.

|

|

1254

|

Representative knights of the Shires were formally summoned to the Great Council, probably for the first time, to report on decisions made in Shire Courts. They were running their local areas through the Shire Courts.

King Henry went to France to pacify the inhabitants of Gascony. He then visited Pontigny to visit the Shrine of St Edmund the Confessor. Edmund Rich had been Archbishop of Canterbury, but died in 1240 at Pontigny. He was canonised in 1247, and should not be confused with St Edmund, King and Martyr, whose shrine was, of course, at Bury St Edmunds.

In Proceedings of SIAH, volume XXXIX part 1, (1997), M Hesse discussed the early estate at Ickworth. One conclusion was that,

"There may have been a small park in Ickworth in the 13th century. In 1254 the King granted

free warren in Ickworth to Thomas de Ickworth (C.P.R.,37-38 Hen. III, Pt. II), and Abbot Simon

of Bury gave licence to 'Thomas our knight .. . to make ditches round his woodland in the vill of

Ickworth, and enclose said wood by a ditch within the bounds set between us and him' (Gage 1838,

278). There is, however, no evidence that this park was ever in fact created, and it will be argued

later in this paper that, if it existed at all in the 13th century, it must have been very small by

medieval standards.'"

|

|

1256

|

Abbot Edmund de Walpole of Bury died on 31st December.

|

|

1257

|

The king's brother Richard, Earl of Cornwall, was elected King of Germany in January. On route to his new kingdom, he stopped at St Edmund's.

On 14th January Simon de Luton, the Prior was elected Abbot of St Edmund's. The Pope refused to confirm him as abbot unless he travelled to Rome in person. Simon was thus the first abbot from any of the exempt abbeys of England to have to go to Rome for confirmation of his election. Not only was this tedious, but also very expensive. This trip cost £2,000, and it now became the norm for new abbots to have to make this journey.

Henry III was persuaded by the Pope to accept the kingdom of Sicily for his son Edmund. The snag was that he would have to raise an army to conquer the island. The Barons refused to provide the money for this venture and the Great Council tried to set up its own Government. It started to think of itself as a Parliament.

Henry the Goldsmith was one of the richest men in Bury and he kept his sheep in his own sheepfold, despite the fact that everybody else had to pay rent to use Abbey folds. Abbey servants raided his farm, beat up the shepherds and scattered the sheep. Henry was sure that he had the legal right to have his own folds, and as many sheep had died following the outrage, he appealed to the King. The king asked Gilbert of Preston, one of his Justices, hear the complaint.

The Bury Chronicle recorded that on 22nd June the Friars Minor entered the town of St Edmund's by stealth. The Franciscans celebrated mass in an audible voice in the presence of all comers, but unknown to the convent. The local Franciscan Friars Minor were saying mass in the home of a local supporter, Sir Roger de Harbridge just by the east side of the Northgate. Meanwhile, when Sir Roger and the Friars sat down to dinner, the Abbey's supporters were demolishing the Friars' Oratory and buildings in an attempt to drive them out.

The friars had considerable support. King Henry III, Gilbert de Clare and many burgesses wanted to help them break the monopoly of the abbey within the banleuca.

During July there was heavy rains and extensive areas were flooded. Much of the corn harvest was destroyed or badly damaged.

Abbey power was again challenged when the Franciscan Friars gained permission from Pope Alexander IV to settle within the Liberty of St Edmund. They set themselves up under the abbey's nose in a farm within Northgate. The abbey expelled them despite the Pope's blessing and the Pope had to call in the Bishop of Lincoln to try to enforce his wishes. He would not call on the Bishop of Norwich for help as he was sympathetic to the Abbot's cause. After this, not only were the Friars thrown out of town, but so was the delegation of the Bishop of Lincoln.

Despite Lavenham being within the Liberty of St Edmund, Hugh de Vere, the 4th Earl of Oxford, gained a charter to hold a Whitsun Fair and a market every Tuesday in his manor at Lavenham. Since Norman times the de Vere family had been lords of the main manor in Lavenham. In 1141 the de Veres became Earls of Oxford, and thus hereditary holders of the office of Lord Great Chamberlain. The 3rd Earl of Oxford was one of the 25 barons of Magna Carta, and now, faced with the 4th Earl, the hard up Abbot Simon of Bury probably decided not to fall out with such a powerful figure. For many years the de Vere main residence was in their castle at Hedingham. They retained a manor house in Lavenham and a hunting park to the north of the town, and must have kept close links with Lavenham and it undoubtedly held a great value for the family.

|

|

1258

|

This was a year of shortages as there had been extensive floods in July of 1257, and the price of corn had now rocketed out of reach of the poor. The Bury Chronicle said that many died of hunger.

The Chronicle also recorded that the great men of the land were exasperated with the Queen, the King's brother, and their French kinsmen who behaved like tyrants wherever they held sway. The king was forced to send them into exile.

On 25th April, the Chronicle recorded a forced entry into the town by the Friars Minor, with royal authority and armed force, led by Gilbert de Preston, the justice of the King's bench. The Chronicle said, indignantly, "This was a violation of the rights and privileges of the Liberty of St Edmund."

In November the king was at Bury when a gale blew down many houses, trees and towers.

|

|

1259

|

Matthew Paris, the great Chronicler, died at St Albans. Much of the known story of Bury and the Magna Carta was recorded by him and Roger of Wendover, his predecessor. For the thirty years after Paris's death there was no more history written at St Albans. The Bury Chronicle becomes valuable to historians after 1265 because of this.

The king sent two writs to the alderman of Bury, over the head of the abbot, asking them to help the Franciscans. The first was in February and called on him to protect and cherish them. The second, in July, ordered him to allow the friars to build a chapel and worship there, despite the opposition of the Sacrist of the Abbey.

Following a nine year law suit, Richard de Clare, the Earl of Gloucester, reached an agreement with the convent over lands in Mildenhall and Icklingham.

|

|

1260

|

A quarrel broke out between the king and the magnates because the Provisions of Oxford had been very little observed. Simon de Montfort emerged as the leader of the Baronage, recorded the Chronicle of Bury.

The Great Council of Barons tended to break into feuding sections and the King started a war to wrest back his control. This is known as the Barons' War. Only the barons who stayed with Simon de Montfort were ready to take on the King.

The debts of the abbey amounting to 5,000 marks, were divided equally between the Abbot and the Convent.

At about this time, Papal Commissioners were sent to Bury to try to sort out the Abbey's dispute with the Friars, but the Abbot refused to see them. The King intervened and the Friars were put up by St Peter's Hospital while their future was pondered.

|

|

1262

|

Pope Alexander died in 1261, and his successor Urban, was apparently less sympathetic to the Franciscans. After he received a delegation from the Bury Benedictines, the Franciscan Friars were ordered to pull down their buildings in Bury and leave town. They did this in November 1262.

|

|

1263

|

The King obtained the Pope's permission to renege on the Provisions of Oxford. The Chronicle records that the barons now sent out men to plunder England. The Bishop of Hereford was locked up and to avoid a similar fate, the Bishop of Norwich fled to the security of St Edmund's Liberty. "For at this time the Liberty of St Edmund was exceedingly precious in the eyes of the barons". The king of France was asked to arbitrate between the parties.

According to the Bury Chronicle, the Friars Minor voluntarily gave up their place in the town, despite the king's order. They had lived there for 5 years, 6 months and 24 days. A papal letter had been received ordering them to leave the said place.

King Henry III was on the side of the Franciscan Friars, particularly because his wife, Eleanor, was a supporter of the whole mendicant movement. The friars wanted to stay in West Suffolk, and with the King's support they were able to do this.

By 1265 the Abbey finally gave the Franciscans land for a permanent home at Babwell just outside the Banleuca where today's Priory Hotel stands.

|

|

1264

|

The King of France said that Henry III was free of any obligation to observe the Provisions of Oxford. War broke out all over England, said the Bury Chronicle.

Simon de Montfort, the Earl of Leicester, defeated the King's army at the Battle of Lewes on May 14th.

However, Simon only won with massive support from citizens of London. Gradually he relied more and more on merchants and small landowners, clergy opposed to the papacy and radical students from Oxford. His forces became less aristocratic and more middle class.

De Montfort's rebellion produced a crisis across the country, and old disputes came out into the open again. At Bury some fairly old grievances against the abbey which had dragged on for years finally erupted in the first of a major series of riots. Abbot Samson's charter of 1194 was the basis of this quarrel, as Samson had kept the wardship of the East Gate, and retained the power to veto town appointments to the other four gates. He also retained the right to hear town cases in his own court.

The story of this uprising comes from the document known as the Pinchbeck Register.

In the Spring of 1264 a group of younger burgesses confronted Abbot Simon of Luton with a series of demands. They demanded to be recognised as a corporate secular guild, in which would be vested power over the town's affairs. Acting quickly, the Guild of Youth was formed in Bury St Edmunds by 300 people in protest against the Abbey. They elected an alderman, setting aside the offically appointed man. They set up a court in opposition to the Portmansmote and restricted the monks to the abbey. The new court had its own horn to summon people to justice.

Street fighting went on for several months, as anyone who ignored their authority was attacked as a public enemy. Eventually they attacked the abbey gate, broke into the cemetery gate, and assaulted the monks. The sacrist and cellarer were thrown out of the town gates, and when the abbot hurried back to Bury, they would not let him in the town. At this time it appears that even some of the older burgesses and even the alderman, supported the Guild of Youth in this. Things carried on uneasily until October when a writ was issued for Gilbert of Preston and William de Boville to hear the abbot's complaints against the Guild. At this royal intervention the older burgesses gradually took fright and withdrew their support. They promised to disband the Guild agreed to accept a fine of £40.The guild or horn was finally disbanded and the Guild of youth's pretender Alderman was also sacked.

The abbot had won yet again, but it had been seen how easy it was to seize power from the monks, and this violent precedent would be remembered again in 1292, when the time was right.

|

|

1265

|

Simon de Montfort summoned a Parliament and invited representatives of the burgesses of the Chartered towns and two knights from every Shire. It contained only five earls and seventeen barons and the balance were from the middle classes.

Gilbert de Clare, the Earl of Gloucester had been a supporter of the Earl of Leicester, but now deserted him in a quarrel over the spoils.

Simon de Montfort was defeated and killed by Henry's son Edward, who had joined with Gilbert de Clare in the Battle of Evesham in the Severn Valley. The monks were, perhaps, sympathetic to De Montfort's cause. They wrote that his body had worked miracles, and a minor cult began to arise. The king now regained power and proceeded to confiscate lands and property and disinherit the supporters of De Montfort.

|

|

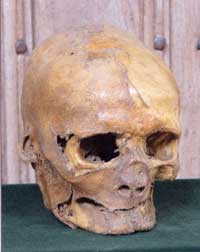

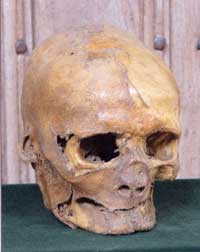

Stone coffin from Babwell Friary

|

|

blank |

In 1265 the Abbey finally gave the Franciscans a permanent home at Babwell just outside the Banleuca where today's Priory Hotel stands. With land given reluctantly by the Abbey at Bury, and financial help from the Earl of Gloucester, Gilbert de Clare, the Franciscan Friars finally founded their Friary at Babwell. The name Babwell no longer survives, but the Priory Hotel stands within the walls of the old Friary precincts at the junction of Tollgate Lane and the Mildenhall Road. Only remnants of the walls remain visible today.

The illustration is of a stone coffin and male burial recorded during excavations at the Babwell Friary, just north of Bury St Edmunds. Beside the head are a pewter communion chalice covered with a paten (plate). This was one of the community of friars; stone coffins were uncommon and suggest that the man was of some importance.

There have also been remains of a mill found behind the Tollgate Inn, possibly associated with the Friary.

However, the Grey Friars still could not enter town without the abbot's permission, and thus were excluded from an easy involvement in civic life. It is not surprising that they tended to side with the townspeople in their disputes with the abbey. In turn they won many friends in town.

They were not the only religious dissidents against the abbey. The rectors with livings in the town, and the so-called secular priests, were treated as second class churchmen by the monks and in turn they also sided with town against abbey. This religious backing was to become important to the burgesses in their growing struggles with the great abbey.

The second great chronicle from the abbey of St Edmund was written from the Creation up to 1265 by the Monk John de Taxter. He became a monk in 1244. A second unknown monk continued the work up to 1296, and a third took it up to 1301. These annals are of little historical use up to 1264 as they are brief and written after the events, but from the Battle of Evesham, they suddenly become detailed and vivid. It seems likely then, that they were started in order to record these momentous events in 1265.

|

|

1266

|

After the overthrow of Simon de Montfort fugitives sought sanctuary within the Liberty and also stored their loot there. These are referred to as the "Disinherited" by the Chronicles. According to the Bury Chronicle, "some of them who were lying hidden at St Edmund's, marched from the town in battle order and invaded the Marshland. They even attacked Lynn".

In May, John de Warenne and William de Valence came to Bury to seek out the king's enemies. They sought out the abbot and burgesses and accused them of helping the disinherited.

This led to a scandal and an enquiry and resulted in the abbot paying a fine of £266 13s 4d to re-establish himself in Henry III's favour. Someone had to take the blame, and now the burgesses were accused of being Montfortian sympathisers. There probably had been a strong support for de Montfort, as he had local supporters like Richard, Earl of Clare, and his son Gilbert, who owned parts of Bury. The earl of Suffolk had also supported him. Specific accusations included that they had let the Disinherited in by lax gatekeeping and had supported the rebels in 1264. This score was now settled as well. To avoid more severe reprisals from the King's justice, the burgesses had to deny that the keeping of the gates was really their responsibility, and that they never really wanted to take over the town. So they dissembled to escape royal wrath, and disclaimed many of the hard won advantages they had recently won. They were also fined and the abbot bailed them out by paying 200 marks on their behalf. In return the abbot was promised £100, but more importantly the town became obligated to the Abbot.

The Disinherited continued to attack the countryside and seized Ely. By December they had raided Norwich and taken 140 carts and waggonloads of loot.

The Dictum of Kenilworth had to be issued to prohibit the cult of Simon de Montfort as a miracle worker. At Bury, the chronicle entry of 1265 relating to these miracles had to be scratched out to conform to the new law.

We know that Bury had a cordwainer's or shoemaker's guild at this time, from a deed recording the transfer of a shop in Cordwainers Street from Geoffrey le Porter to Guild for its headquarters.

|

|

1267

|

The king knew he had to put down these rebellions in the Fens, so King Henry III came to Bury St Edmunds on February 6th. Next day the papal legate Ottobuono also arrived. All the prelates and magnates of the land had been summoned by both church and state to attend. On February 22nd the legate held a council in the king's presence to excommunicate the Disinherited who were occupying the Isle of Ely, together with all their supporters unless they gave up within 15 days. This caused such discontent that certain rumours so scared the Legate that he left for London within 24 hours. The town was obviously still in turmoil, and lawlessness was still common. Robert of Bradfield and John of Punchardon were appointed keepers of the town to try to restore order. The king also took his court out of Bury to meet his army at Cambridge, and on to besiege Ely.

Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester now marched on London while the king was at Ely. The King had to leave his siege and hasten back to the capital, and a truce was made on June 18th.

Meanwhile some ruffians came out of Ely and stole horses from the Liberty of St Edmund, according to the Bury Chronicle. A monk seems to have negotiated them back again, and in July the king's son Edward regained the Isle of Ely.

Rabbit warrens become popular in the 13th century and free warrens were granted in Haverhill to Hamo Chevre by Henry III in 1267, and later to Roger Lunedaye by Edward I in 1281.

|

|

1268

|

The Abbey was assessed for taxes under the auspices of the Bishop of Norwich, when the king assessed all ecclesiastical revenues to tax at their "true value". The monks felt this was against the rights of the Liberty, but nevertheless they submitted. The assessments were recorded in great detail in the Bury Chronicle. It was also recorded that the monks paid the episcopal assessor and collector 20 marks to overlook the tax due from the ir holdings within the town of Bury, but this failed.

The Chronicle seems to ignore the happenings outside the abbey walls. In September the king "impleaded" the alderman and 24 burgesses for ignoring the orders of the keeper of the town, Robert of Bradfield. There were some fines levied by the justices in eyre in Cattishall, and the situation seems to have calmed down.

|

|

1270

|

The Chronicle recorded the death of Roger Bigod, earl of Norfolk and Suffolk, and marshal of England, at Cowhaugh. He was buried at Thetford, and his inheritance went to another Roger, the son of his brother, Hugh Bigod.

In 1190 Abbot Samson had expelled the Jewish community from Bury St Edmunds. However, we know that in 1270, a Jewish businessman called Moses of Clare, lived near Sudbury within the Liberty of St Edmund. It is likely that some commercial links would be retained with Bury, and it is possible that he either owned or rented Moyse's Hall in Bury. There is a tradition that Moyse's Hall was built as a Jewish Merchant's house around 1180. In this case Moses of Clare could not have built it himself, even if he occupied it 90 years later. Today it is a town museum.

|

|

1271

|

Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester divorced his wife Alice at Norwich. According to the Chronicle he had suspected her of having an affair with the king's son Edward in 1269, and had quarrelled with the prince, but made it up.

Marco Polo began his voyages to the east and continued until 1295.

|

|

King Edward I

|

|

1272

|

The Bury Chronicle recorded a great assault upon Norwich abbey by 32,000 men of the town, "armed to the teeth." There was loss of life and massive destruction. A council of the whole diocese was held at Eye to excommunicate everybody involved. The king set out to Norwich to punish the city, and called a council meeting to consider the action necessary.

King Henry III held this Parliament at St Edmund's Abbey, on route to Norwich, arriving in Bury on September 1st and leaving on the 15th. While there, he signed a warrant to transfer the Jewish Synagogue in London over to the Penitentiary Friars, the Brothers of Penitence. Not surprisingly the Chronicle says, "to the utter confusion of the Jews."

At Norwich there were 35 executions and many fines threatened to make recompense for the crimes against the abbey, but the monks of Bury felt the king had "compromised a little, doing only partial justice for the outrage."

King Henry III, "of happy memory", died on November 16th, having reigned for 56 years and 29 days. Edward I came to the throne and reigned until 1307. However he was abroad at the time, so the country was put in the hands of Gilbert de Clare and Edmund, Earl of Cornwall.

From 1272 until 1278, the Long Cross Coins were still being issued under Henry III's name. Only 3 mints are known to have worked at this time, being London, Durham and Bury St Edmunds. Strangely, the Bury coins are the commonest of the three today.

In the

late 13th century the Maison Dieu or God's House was founded, a substantial almshouse near St Petronilla's hospital in Southgate Street in Bury.

|

|

1273

|

In March there was so much rain that there were floods worse than any since 1258. Water rose 5 feet above the bridge at Cambridge, and the damage at Norwich was said to be worse than the ravages of either the disinherited or the king's men last year.

The Bury Chronicler recorded another tax levy to support the needs of the new king.

|

|

1274

|

Prince Edward returned from abroad for his coronation. Edward must have liked Bury as he seems to have visited the town at least 15 times in his reign, and kept a permanent residence in the abbey complex.

To illustrate the involvement of the Sacrist in matters of local justice, we hear him accused of holding an iter or sitting at Bury for a longer period than the King's Justices had sat at Cattishall.The Sacrist was sitting as a Justice in eyre or Justice of Assize, appointed by the Abbot as part of his responsibility for carrying out the King's Justice within the Banleuca. The portman-moot seems to have declined greatly in the administration of local justice by this time. The local laws were being appropriated by the state more and more, and through this mechanism to the abbot and the abbey sacrist and his bailiffs.

|

|

1275

|

The new king, Edward I, came with his wife to Bury, on a pilgrimage, in accordance with a vow made in the Holy Land. He granted the convent the right to hold the view of weights and measures, without any of his officials being present. For this right the abbey paid him 100 marks. According to Lobel, this was not the first such grant, and this liberty may have existed already since the time of Richard I.

The last major addition to the fabric of the abbey was perhaps the new Lady Chapel built by Abbot Simon of Luton in 1275. The Chronicle recorded that the old chapel of St Edmund was pulled down and the Lady Chapel built on its site. Under the earth were found the walls of an ancient round church, which was much wider than the chapel of St Edmund and so built that the alter of the chapel was, as it were, in the centre. "We believe that this was the chapel first built for the service of St Edmund." It could have been the foundations of Ailwin's stone chapel of 1032, or maybe even stone foundations to the wooden church first built in 903.

Another tax of the 15th penny was recorded in the Chronicle, as well as the 10th penny decided at the Council of Lyons by the Pope. By this time heavy taxes and other financial weaknesses seem to have hit the abbey at Bury very hard, and retrenchment replaced expansion. Only small additions to the building programme would now be possible, if any at all.

The king finally announced the fines and penalties to be paid by the Burgesses at Norwich for the attack on the abbey there in 1272. At Cambridge the King allowed his mother, Eleanor, the right to expel all the Jews. She was allowed to do this in all her dower towns.

In the mid 13th century the average sea level at Great Yarmouth is estimated to have been 4 metres lower than at present. There were many more coastal salt marshes around Suffolk then than there are today. This situation seems to have changed after about 1275, when sea levels seem to have begun to rise.

From 1275 to 1345 the coast of East Anglia would suffer many major inundations by the sea. The weather seemed to turn stormy followed by violent swings in weather patterns accompanied by large marine surges. Thousands of acres of salt marsh would be flooded, coastlines altered and harbours washed away. The most notable casualty would be Dunwich which had been a major port. It would lose six parishes, over 600 buildings and its harbour mouth between 1275 and 1345. Over 80 acres of salt marsh disappeared below the sea here.

|

|

1276

|

At Cambridge a great part of the town, including St Benet's, was burnt down. Even more seriously, the Chronicle recorded that a deadly disease began to afflict sheep in Lindsey. It lasted many years and spread over most of England.

|

|

1277

|

The King sent a large army to Wales. Before joining them he came to Norfolk and Suffolk, keeping Easter at Norwich. This resulted in yet another round of taxes recorded by the abbey chronicle. This time the town's tax was paid by the convent to be collected from their tenants at a later date.

A cloudburst in October caused many men and livestock to be drowned in the floods. The storms were worst in Essex and Cambridgeshire and around Bury itself.

|

|

1278

|

The King and Queen arrived at Bury on 23rd November on route to Norwich to dedicate a church there.

All the Jews in England were unexpectedly seized and imprisoned. Their houses were ransacked looking for evidence of clipping the king's coinage. Soon afterwards in November all the goldsmiths and officials of the country's Mints were also put into custody and their premises searched. At Bury, despite the privilege of the Liberty, five goldsmiths and three others were marched off to London by the town bailiff. The king then allowed them to be sent back to Bury for trial, as a special favour to St Edmund.

|

|

1279

|

All the Jews and some Christians convicted of clipping or falsifying the coinage, were condemned to hanging. Some 267 Jews were condemned to death in London.

John de Cobham and Walter de Heliun, were the justices appointed to determine pleas over money, and they were sent by the king, Edward I, to Bury to hold a court at the Guildhall. The monks regarded this as flouting in an unheard of way, the liberties of St Edmund's church. Even worse, any fines levied went to the royal Treasury, and not to the abbey convent. Because the Sacrist was in charge of the Mint at Bury, he was also fined 100 Marks for the transgressions of the moneyers.

Holding their enquiry at the Guildhall shows its importance in the town by this time. This is the earliest known written record of the existence of the Guildhall in Bury St Edmunds, but evidence from recent examination of the rear of the building shows that it may have originated a century earlier. The earliest reference to Guildhall Street itself comes from the 1290s.

Simon, the abbot at Bury, died at his manor of Long Melford. The king, as was normal, took over the revenues due to the abbot until a successor was in place. However, going against precedent, he also took over the income due to the convent of monks at the abbey. The monks were allowed only enough for their sustenance by John de Berwick, the king's agent.

Meanwhile, John de Northwold, a Bury monk, and the interior guest master, was elected Abbot. He had to travel to Rome to be confirmed in his position and had to be empowered to pledge the credit of the convent up to £500, to pay for the trip. When he got back, the king ordered Berwick to restore the barony to the abbot and the rest to the convent on November 5th 1279. The trip cost the abbey 1,675 marks, 10 shillings and 9 pence. Abbot John would rule the Abbey until 1301.

The coinage was altered this year. The triangular farthing, made by cutting a penny into four quarters, was replaced by a round one. Half pennies were abolished and a new four pence coin was invented. This was the first groat. According to the Bury Chronicle, the abbey did not receive new dies for this coinage until June, 1280.

|

|

ROBE/RTDE/HADE/LIE

|

|

1280

|

In June the Bury Chronicle recorded that the new coinage began to be produced at Bury. The old coinage could no longer be used after August 15th, Assumption Day. Apparently new round halfpennies were minted.

Suffolk's only mint was at Bury St Edmunds. In general these new coins gave the mint name in full and omitted the name of the moneyer for the first time since the 9th century. Curiously enough, some issues from Bury St Edmunds were the total reverse of this policy, giving the moneyer's name in full, ROBERT DE HADELIE, and omitting the mint name.

Robert the Prior, resigned due to his paralysis, to be succeeded by Stephen de Ixworth, the sub-prior. Simon of Kingston, the Sacrist, also resigned, to be replaced by William de Hoo, the Chamberlain. William of Hoo is noteworthy as he left us his letterbooks, published by the Suffolk Records Society in 1963, edited by Antonia Gransden. The Letterbook of William of Hoo covers the years from 1280 to 1294.

|

|

1281

|

To avoid any repeat of the loss of the convent's income to the king, Edward I was asked for a new charter to separate the property of the abbot and the convent. This was agreed, but it cost the convent 1,000 marks, plus a considerable sum in other expenses. This was simply the final and most complete separation of the Abbot's incomes from those of the Sacrist for the convent of monks. The monks knew this well enough, but it was needed to protect themselves from the crown in times when the post of abbot was vacant.

In 1281, the manor of Haberdon, or Haberden, was granted to the Sacrist of the abbey by Henry, son of Nicholas of St Edmund. This would add to the sacrist's income, and included a mill, and at least 51 acres. As the abbey gained more and more of the local pasture land, any common rights hitherto exercised by local people were gradually extinguished by the new owner.

|

|

1282

|

Prince Llewelyn of Wales rose in revolt and destroyed some of the king's castles. In response, Edward I levied a subsidy in the form of loans from all his cities and boroughs and from the clergy to pay for his campaigns in Wales. In June, he sent John de Kirkby, the Archdeacon of Coventry around the country to raise the loans. It seems that he was given a quota of money to raise in each location. Bury was assessed without the wealth of the Abbey, and was shown to be of only middling prosperity at this time, according to Gottfried. However, Bury was above Cambridge and Ipswich in the lists.

-

London's assessed value at the top of the list was £4,000.

- Newcastle was next at £1163.9.0,

- York was third at £693.6.8.

- The assessment was £666.13.4 for Great Yarmouth, which was fifth highest.

- At number eight was £333.6.8 for Norwich

- Number nine was £266.13.4 for Bury.

- Lesser towns were Kings Lynn at £200,

- Ipswich at only £100, (the same as Orford), and

- Dunwich by now was at £66.

By the time of the 1327 subsidy rolls, Ipswich would overtake Bury in its value for taxation purposes.

The Bury Chronicle recorded the subsidy as 8,000 marks for London, 1,000 marks from Yarmouth, £500 from Norwich, and 500 marks from the burgesses at Bury. But the monks' servants had to pay 26 marks, and the prior assessed the Guild of the Twelve at 12 marks. The monks recorded that 100 marks were extorted from the abbot and convent.

By November, it was clear to the King that these loans were nowhere near sufficient to pay for the war, and he summoned a Parliament to York, and another to Northampton, to meet In January next.

A record in William of Hoo's Letterbook concerns a lease of a toft, or shop, in Icklingham, together with a Fulling Mill. This would have been located on the River Lark, using a combination of water and Fuller's Earth to clean the grease from Woollen Fleeces. William the Sacrist would receive his annual rent from the lessees, Robert the Fuller of Icklingham and his wife Cecily.

|

|

1283

|

In January, Parliament voted the King a taxation levy or subsidy of one thirtieth part of the moveable goods of all subjects, to pay for the Welsh war. Those who had made the loans in the previous year could offset these against the levy. Bishops, Archbishops and certain Earls who were fighting for the king, would be exempt. Also exempted were those who owned goods worth less than half a mark. The Collectors appointed for Suffolk were sworn in during February. They were John de Mettingham and William de Pakenham, assisted by Simon de Dagworth and the Sheriff, William de Royngs.

It would appear from Edgar Powell's research that, out of the whole country, the only Lay Subsidy Rolls to survive from the 1283 Subsidy, were those for Ipswich, and those for the Suffolk Hundred of Blackbourne. What does survive is a list of the Subsidy due from most of the English counties. Suffolk appears fifth in this list.

- Lincolnshire £4018.12.8

- Norfolk £3684.2.6

- Kent £2880.12.7

- Yorkshire £2860.1.9

- Suffolk £2103.18.8

The Hundred of Blackbourne was far from typical of Suffolk Hundreds. It was valued as a Double-Hundred, and had originally been the two seperate Hundreds of Broadmere, or Bradmere, and Blackbourne. Vills which had been recorded as in Bradmere in 1086 included Ingham, Culford, West Stow, Barnham, Barningham, Ixworth, Sapiston, Wyken, Langham and Hepworth. Wordwell, however, which was surrounded by West Stow, Barnham and Culford, was in Blackbourne Hundred in the Domesday Book of 1086. Anomalies like this may have been the reason why the two Hundreds were apparently joined together by about 1100.

According to a document in the Letterbook of William of Hoo, Sacrist to the Abbey, there was a grave incident surrounding the murder of William, Rector of Woodhill, possibly Odell in Bedfordshire. This murder took place near St Mary's church in Bury, and Geoffrey of Redgrave and 12 other young men were present at the murder. Geoffrey and two other men were described later as goldsmihs and clerks. The clerical role gave them some status as clergymen. Another man was a servant of Robert de Hadleye, the Bury moneyer, and one was John of Thetford, also a goldsmith.

The two clergymen may have expected to be tried by the abbot's court, but he declined to claim them, and they were imprisoned.

An inquest was held on the case in February of 1283/84, by Bailiffs appointed by the Abbot. Two men were cleared of murder but convicted for falsifying the coinage and robbery. They were drawn and quartered. Three more were cleared and four of them were hanged for a number of crimes.

This was obviously a very involved case as the murder itself was not the whole story.

Behind the crimes was also the issue of jurisdiction. The Town Alderman should have run the prosecution, but he decided to leave town on the grounds that he was old and too infirm to deal with the case. So the town's Bailiffs at first tried the men and imprisoned them. The sister of the dead man, Eleanor de Gowiz, objected to this and appealed to the King for justice.

The King did issue a mandate to a team to investigate the crime. Abbot John, jealous of this interference in his area of control, sent his own representative to the King to point this out. The King now gave the Abbot the mandate to supervise an inquest by his own nominee Bailiffs. This inquest handed down the sentences already discussed.

After the Inquest, the Abbot's Bailiffs took the whole vill of Bury into the Abbot's hands on the grounds that the Alderman and Town Bailiffs were not up to the job. Next day the Abbot talked this over with the Convent of the Abbey, (ie the body of monks) and decided to restore the vill to its former position, but only after the alderman and burgesses had "bought his favour."

This whole involved issue must have had many aspects behind it which are lost to us today, apart from these bare facts. The issue gets even more involved when we find that in 1293 Geoffrey of Redgrave and John de Perers, both described as Goldsmiths and Clerks, are released and "restored to their good fame."

|

|

1284

|

By this time the Manor of Erbury was established in Clare and a manorial complex with associated fishponds has been identified within the walls of Clare Camp. Clare Priory was built in 1284 when Friars of the newly formed Augustinian Order came to England at the invitation of Richard, Lord of Clare. It was the first British base of the followers of St Augustine of Hippo.

Woodland was scarce and valuable in Suffolk. Much of it had been grubbed out and converted to arable, but the surface of Suffolk had only contained 10% of woodland in 1086. By 1349 Bailey thought that half of that meagre total would have gone under the plough. So what was left was intensively managed, often in fairly small plots.

Elmswell had a large wood at 160 acres and Hitcham had a 246 acre wood, while Hartest had a 100 acre wood and a 12 acre grove.

In the 1280s there was an 8 acre wood at Rickinghall. William de Monastery was tenant, but holding only 1 acre while John de Croue held 7 acres as his under-tenant. Little Whelnetham had eight separate woods ranging from 2 to 10 acres, held by small lay manors or free tenants.

English rule over Wales was established.

|

|

1285

|

Giotto was active in Florence, representing the first major flowering of Renaissance art.

On 20th February, the king, Edward I, arrived at Bury with the Queen and his three daughters, to fulfill a vow he had made on his Welsh campaign. Next day he set out for Norfolk. He upset the monks by having all the weights, measures and ell-measures of the town inspected by his marshall of measures. They believed that this was the job of the Sacrist and his bailiffs, because it had been the subject of a specific grant by the king in 1275. But it seems that on this occasion the burgesses had prevented this from happening until a royal visit was due. After a local hearing, the king granted all the profits from the inspection to the shrine of St Edmund. But he warned the abbey to ensure that weights were checked or "viewed" twice a year between his own visits in future.

The king's Clerk of the Market, Ralph of Midlington, continued to exercise royal power over local trade, in a strict manner, until after the death of Edward I.

|

|

1286

|

News came of a terrific storm at sea, which battered the land so badly that the great city of Dunwich was severely damaged. On three nights early in 1286 a huge storm raged, sweeping away the lower parts of the town and joining the harbour's shingle spit to the coastline to the south of the town. Dunwich no longer had a harbour. Channels would have to be dug through the shingle to enable some maritime access to the town.

Dunwich was the home of an ancient bishopric. Some people believe that it possibly dated back to the time of St Felix, who came from Burgundy to assist King Sigbert in setting up Christianity among the pagan Anglo-Saxons in about 630.

After 1066, Dunwich became part of the Honour of Eye, under Robert Malet and his descendants. Even in 1086 the town had suffered from coastal erosion, but despite this it rose to become a great town, getting a charter from King John in 1199. By 1298 Dunwich would get the right to send two MP's to parliament, and became a great seaport, with trade, fishing and shipbuilding industries. Further damage would occur in 1328, and Over the 14th century its economy would be largely destroyed by coastal erosion, reducing it to a small and declining fishing town.

|

|

1287

|

In January the justices in eyre sat at Cattishall as usual, just outside Bury, near Thurston.

John de Creyk, Godfrey de Beaumont and Ralph de Berners sued the abbey over the manors of Semer and Groton. Fearing that they would lose the case, the monks chose to defend their rights by judicial combat. The abbot hired a champion called Roger Clerk to fight for him, paying him 20 marks in advance, and 30 more to be paid afterwards. This seems to us a very strange way to settle a legal case, and even at the time it must have been an almost obsolete idea, as such duels were from an earlier age. The fight took place on 14th October in London, and Roger Clerk was killed. The manors of Semer and Groton were thus lost to the abbey, but were regained in 1290.

William of Hoo, the abbey's Sacrist, installed Richard de Lothbury, a goldsmith of London, as moneyer for the abbey. This had to be done by presenting him to the Barons of the Exchequer and then a new die was cut in his name.

We know about this from the surviving Letterbook of William of Hoo, 1280-1294, published by the Suffolk Records Society in 1963. Among his many other valuable privileges, the Sacrist controlled the minting of money in the town under a royal warrant.

|

|

1288

|

During the 1280s Sir William de Pakenham was a typical landed knight of the shire. Mark Bailey gave him as an example in his book on "Medieval Suffolk". He owned four manors in Norton, Ixworth Thorpe, Thurston and Bardwell earning him between £25 and £40 a year each. He had smaller manors in Great Ashfield and Pakenham which brought him another £10 a year each. In all, he received about £200 a year, which gave him enough spare cash, after expenses, to spend £140 buying up land at Ixworth Thorpe to provide for his younger son, Thomas. He served as a senior administrator on the estates of the Abbey of St Edmund and the Bishop of Norwich. He was one of two tax collectors in Suffolk for the Lay Subsidy of 1283. Sir William was a farmer and administrator. None of his wealth came from soldiering, the other main way to get rich quick at the time.

Sir William was wealthy by the standards of most landlords. Lesser men could still consider themselves gentlemen on £12 a year, considered to be the average for English lay landlords holding one small manor.

Two men who owed service to Sir William were William de Thelnetham and Ralph de Bardwell. William held a manor at Troston and land in Barnham. He made £15 a year. Ralph had manors in Bardwell and Hunston making perhaps £20 a year. They would support Sir William in any actions he took, protecting their own positions by his friendship.

In the 1280s the largest manors in West Suffolk were associated with the great ecclesiastical landlords, mainly of the Abbey of St Edmund. For example, in Blackbourne hundred, Bailey has pointed out that Bury abbey held seven manors with an average of 320 arable acres and 280 acres in villeinage. In contrast, the 37 lay manors in the hundred averaged about 100 acres of arable and 31 acres held in villeinage. The bishop of Ely held a manor in Brandon of 564 arable acres and the same again under villeinage. The prior and convent at Ely abbey held 600 arable acres in Lakenheath, and the same again let under tenancies.

However, a majority of vills, including Lakenheath were not in the hands of just one landlord. The earl of Clare held 100 arable acres in Lakenheath alongside Ely abbey, while Melford contained a number of manors. At Long Melford, despite the Bury Abbey holding an 800 acre demesne, plus 600 acres of villein land, there were the manors of Kentwell, and a number of smaller ones.

Over the centuries the less powerful landlords had witnessed the fragmentation of their estates by inheritance or the need to retain favour with more powerful neighbours and up and coming tenants. Only the most powerful of lay lords, such as the Earls of Norfolk, based at Framlingham, could retain or even enhance, their holdings. By the 1280s the remainder of Suffolk generally had smaller manors than in the Liberty of St Edmund.

With the growth in population there was a greater demand for food and farming was intensified where possible, and new land turned to arable where possible. By the 1280s it has been calculated by M Hesse that 74% of the surface of the parish of Ickworth was ploughed for grain production. This was probably a 25% increase over the arable proportion since the Domesday survey. Much of this would pass into the growing towns and their markets.

Some manors in north-west Suffolk had another resource at hand. In the valley fens as well as in the great fen, there were pockets of peat. The product of the peat bogs was turves, and the resource was known as a turbary. Turves were probably the single most important source of domestic fuel in East Anglia in the 12th and 13th centuries. The manor of Coney Weston had a small turbary of 2 acres in the 1280s. Hopton contained a 10 acre turbary. The vill of Pakenham was owned by the abbey of St Edmund, but the abbey's tenants there had access to 400 acres of common pasture, marsh and turbary rights.

Residents of Eriswell could cut 4,000 turves a year for their own use. In Brandon the locals could sell thousands of locally dug turves to outsiders. In Lakenheath the locals had to cut around 100,000 turves a year to send to the Abbey of Ely, who owned that vill.

The biggest turbaries, however, were in the area of north-east Suffolk and South-east Norfolk. Bailey suggests that these workings produced 12 million turves a year in the 13th century. When these diggings eventually became flooded over the following centuries, the Broads would be formed.

|

|

1289

|

King Edward I and Queen Eleanor visited Bury St Edmunds, having returned from three years abroad. They landed at Dover on 12th August, proceeding through Kent and Essex, reaching Bury on 12th September. Next day they went to Norfolk, then through the Isle of Ely by boat to be in London by mid November.

The king's chief justice, Thomas Wayland was indicted for harbouring some of his own men who had killed another man. He feared the King and so fled to Bury to take sanctuary with the Friars Minor, the Franciscans at Babwell. On the king's orders he was besieged by men of the neighborhood for several days. He even became a monk, or "assumed the habit", but this just caused the king to send further reinforcements to his blockade. After two months Wayland admitted defeat and gave himself up, and was taken to the Tower of London.

|

|

1290

|

The king held a Parliament in Westminster to discuss the wrongdoings of some Justices. Among them was Thomas Wayland, who had all his property confiscated, and was sent into exile. He had held the manor of Onehouse from St Edmund's abbey, and had been an important East Anglian landowner.

A man called John Harrison tried to set up a new song school in Bury to rival that provided by the Dusse Guild. He was backed by the Abbot, John of Northwold, in an attempt to bring this teaching under abbey control. The Guild, however was rich and powerful and protested against it. The Abbot was forced to withdraw his formal support and the new venture then collapsed. The town was proud of this bit of independence from the abbey, and this time was able to come out on top.

The cellarer had dammed up the Tayfen brook, and flooded some lands used by towns people. The leading townsmen were united against this act, and called a meeting in the Guild Hall. They then set out to destroy the dam. In October, a commission was set up to enquire into their actions, but this only made matters worse. This rumbled on into more violence in 1292.

The Bury Chronicle recorded that the king "exiled without hope of return all Jews of both sexes and every age living in England."

|

|

1291

|

The abbot and convent of St Edmunds' paid a fine of 1,000 marks to the king in lieu of paying a fifteenth of their own property and that of the burgesses of the town, lest the royal officials should try to do anything which would prejudice the liberties of St Edmund's Church. The abbey officials then levied the tax themselves on the town.

To emphasise the importance of monastic chronicles in recording history, we can examine the King's claim to the overlordship of Scotland. In July 1291, he sent copies of letters of allegiance to all the main monastic houses instructing them to "have these letters recorded in your chronicles so that these events are remembered forever."

|

|

1292

|

The pope granted the king a tenth of all the spiritual revenues in the land, and the abbey was included in yet another tax. The Bury Chronicle recorded the assessment in great detail. It came to £1,098:8s:8d for all the holdings in Norfolk and Suffolk. The tax was £109:16s:11.

With his son and daughters, the King came to Bury on 28th April, and celebrated the Feast of the Translation of St Edmund with full rites. For ten days he divided his time between Bury and Culford, the abbot's manor three miles from Bury. He granted a charter saying that the the session of the king's justices should not be taken as a precedent to the prejudice of the abbot and convent.

The events of 1292 recorded above were in the Bury Chronicle. The following events in that year did not get mentioned in it.

Old grievances erupted again in 1292 over the control of the town gates, and who ought to run the town's secular affairs. The violence was not too extreme, but, following some riots, the burgesses of Bury proposed to the Abbot, John of Northwold, that his Port Reeve should be replaced by a town nominee. Their man was called John the Goldsmith. The Port Reeve was the abbot's man who ran the secular government of the town. The burgesses proposed that the head of the Town Guild should be given this right and that he should be called the Mayor, as the first citizen was called in the Boroughs like Thetford and London.

Abbot John objected as the Guild was a commercial body but the office of Port Reeve had wider governmental powers. The abbot took the case to court, but eventually, before the case was concluded in 1293, he agreed to a compromise. He would allow the new post to be called Alderman, but not Mayor. He would not accept that the town should have a free hand in the appointment, and insisted on selecting one man from the three nominees he would let them propose. But it seems that John Goldsmith still got the job on this occasion.

This arrangement lasted until the Dissolution, with the town gradually increasing its say over who was selected. The Town Guild now became called the Alderman's Guild, and the new office came to have considerable influence in town affairs.

By 1292 the position of the old borough court, the portman-moot, was considerably undermined. The burgesses still claimed that their pleas should be heard in the toll house where the town's judicial affairs had traditionally been held, and not before the king's justices in the abbot's hall of pleas. The abbot insisted they met wherever he said, and his will prevailed, but the argument continued on for years.

|

|

1293

|

The Chronicle recorded two great sea battles between the English, allied with the Irish and men of Bayonne, and the Normans. Thirty captured Norman ships were taken to Yarmouth laden with booty.

On 9th July a great part of Cambridge was burnt down, including the church of St Mary.

There were two lawsuits between the town and the convent during the reign of Edward I, according to Lobel. These were settled in 1293. One case was described above and the other confirmed that all burgesses must be in tithing. For years they had had to pay a yearly tithe of one penny, also called borth-selver, whether or not they were already paying hadgovel or ground rent for their tenements. The town had challenged this, and whether the view of frankpledge was due to the sacrist at all if he was already receiving these other payments. The town lost and this tithe was now to continue as before.

In 1293, Geoffrey of Redgrave and John de Perers, both described as Goldsmiths and Clerks, seem to get their convictions for the murder, in 1283, of William of Woodhill overturned. On the order of Abbot John, they were admitted to Compurgation, released and "restored to their good fame."

Compurgation, also called wager of law, was a defense used in earlier times, whereby a defendant could establish his innocence or non-liability for a crime, by taking an oath and by getting a required number of persons, typically twelve, to swear they believed his oath. Not surprisingly, this defence had been abolished in civil law in 1164. The Church, however, continued to accept this defence.

The murdered man's brother, Sir John of Woodall, objected to this process unsuccessfully.

Also in 1293 the Prior of Ixworth and the convent of Ixworth monks, were granted the right to be free of tolls at Bury. In return, Prior Reginald agreed to pay the Abbey Sacrist 3 shillings and a quarter of cinnamon a year, plus the rents from three shops in Bury, in Heathenmans Street and Eastgate street.

|

|

1294

|

The king came with pious devotion to St Edmund's for the Feast of St Edward on 18th March. He stayed only one night but he entertained the convent with great magnificence and generosity.

At this time he sent letters of resignation of his lands in Aquitaine and Gascony to the king of France. He wanted to marry Blanche, the sister of the French king, and thus regain them by marriage. The monk who wrote the Chronicle recorded that all this was thoughtless and ill advised. When he got neither a wife or his lands back, the king raised an army to invade France.

Among others, the Abbot of St Edmunds had to pay knights fees of 600 marks in lieu of 6 knights, for whom he was bound to answer to the king. All the ecclesiastical houses were visited by the king's inspectors to make sure he got all the money due to him. At Bury the Chronicler was enraged that this invasion also included St Edmund's.

All of the alien religious houses except the Cistercians, were taken over by the king. Presumably this was part of his fund raising exercise. They included the Cluniacs, Premonstratensians and the rest and all their property was confiscated, forcing them into "poverty, misery and sorrow".

The Welsh rose in rebellion. Yet another tax of the tenth was levied, and royal tax collectors again entered Bury to collect it. Never before had a royal official dared exercise authority in the town, sitting in the toll house. Once again the king said this did not set a precedent.

Edward I had proved a heavy handed monarch as far as the church was concerned, and this had cost the abbot dear in legal expenses on several occasions before and since.

|

|

Churchgate and College Streets

|

|

1295

|

In 1992 a survey of 48 and 49 Churchgate Street and 1 College Street in Bury revealed that the whole property

was originally an aisled hall dated to the second half of the 13th century. It has two jetties and is likely to be amongst the earliest known examples of this feature.

Edward I was faced with wars in France and Scotland and holding down the recently conquered Welsh. He summoned his "model parliament" to grant him the taxes needed to run these campaigns.

This was the first time that boroughs, including Bury, were summoned to send representatives to Parliament, alongside the earls and barons. The sheriff of each county was directed to return two knights of the shire for each county and for such boroughs and cities as he might deem suitable, two burgesses or citizens. Thus the sheriffs were the "Returning Officers", and remain so today, in theory.

For the first time this Parliament started to look like a representative assembly. However, after the time of Edward I, Bury was never asked to send burgesses to parliament again until after the charter of 1606. The abbot continued to attend as a Lord Spiritual, but it is likely that he was offended by having to sit with a town burgess in Parliament.

|

|

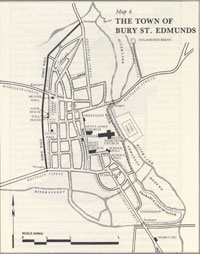

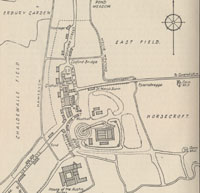

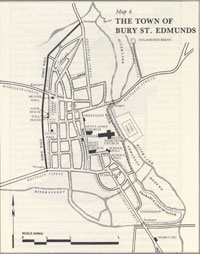

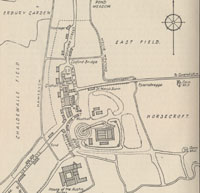

Bury in 1295 by R Gottfried

|

|

blank |

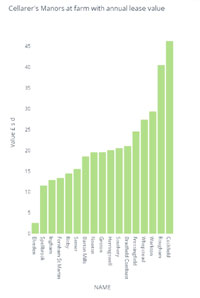

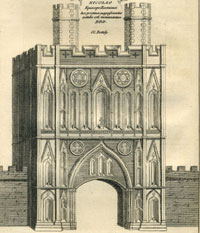

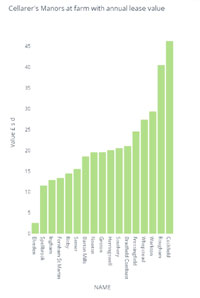

The tax collectors in Suffolk were Peter de Melles and Ralph Bomund, but the king agreed to mend his ways and let the ecclesiastical powers collect it for him where those rights and liberties applied. So the Prior at Bury was allowed to collect this tax in the Liberty of St Edmund.