Anglo Saxon remains

Anglo Saxon remains

Westgarth Gardens

Quick links on this page

Saxons take over 442

Arthur leads resistance 470's

Battle of Badon 495

Gildas writes History 538

London and St Albans fall 570

Raedwald rules 599

Sutton Hoo burial 625

King Sigbert sponsors Felix 631

St Audrey's Ely nunnery 673

South Elmham Minster 680

Beowulf written 710

Bede writes History 731

Vikings sack Lindisfarne 793

Foot of Page 855

|

The Anglo-Saxons

and the origins of

The English People

410 - 865

Before

410

|

The text below from 406 to 410 sums up the last years of direct Roman rule over Britain. Please click on the heading if you would like to go back further into the history of Roman Britain before 410.

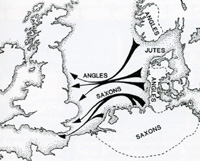

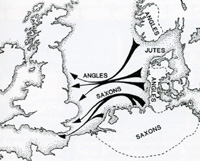

In 406 the Roman Army was withdrawn from Britain to deal with an invasion into Gaul of the Vandals, Alans and Suevi from across the Rhine. In 407 the Rhine froze over and this gave the Vandals easy access to the wealth and comforts of the Empire. In 409 a major Saxon invasion took place in Britain without the Roman army to repel them. Saxons had raided the East coast early in the 3rd century and from 270 to 285 the Romans had built the Forts of the Saxon shore to cope with the threat. In addition, the Romans had employed some Germanic peoples as mercenaries and settled them in Britain to help with defence. By 410, the country of Britain was being left to maintain itself as best it could, as part of the Empire, but without the Empire's old might and resources to sustain it.

The period which followed has been called the Dark Ages, because there was no longer anybody recording events for the next two or three hundred years.

|

|

410

|

In the year 410, the cities of Britain were officially ordered by the Emperor Honorius to take responsibility for their own defences. In the same year the Goths took Rome and an important result of the collapse of central Roman rule was that no further coinage was imported into Britain. In addition, no coins seem to have been minted in England from 411 to about 630. However, we may judge that existing coinage remained in circulation for some decades, and other coinage would have arrived with foreign traders, even if there was no further official money issued here.

It was the beginning of the end - administrators, specialists and the military could not be supported by the arrival of the official paychest. Other means of survival had to be found.

From 410 to 442, Britain was independent from Rome, and this was to be the last fading age of Romanised Britain before the Saxons were to effectively take over.

|

|

411

|

The Gallic Chronicle of 452 reports a dreadful Saxon raid on the Channel coasts in 411.

In the same year a British Bishop, Fastidius, wrote of magistrates violently killed, some lying unburied, suggesting the violent overthrow of a government by their own people. Constantine's supporters had been overthrown in the recent past, and now that Honorius had washed his hands of Britain, perhaps the Constantine faction had again taken control.

Constantine himself had been elected Emperor in Britain in 403 AD and had then led a military expedition into Spain. In 411 he was taken prisoner in a battle at Arles, and subsequently murdered. Britain's connections with Rome were being severed. No more coins were produced in Constantine's name in Britain, and no more finance flowed into Britain from Rome.

At about this time, the so-called Sicilian Briton developed an advanced egalitarian political philosophy based on Christian principles of the virtues of poverty and the poor and urged abolition of the rich.

In describing the period from about 411 to 425, Gildas wrote that kings were anointed and soon after slain by those who had anointed them, but the people were prosperous.

|

|

418

|

Roman imperial Government outlawed the Pelagian doctrine, but this had no effect in Britain for decades, where it was introduced in 421 by Agricola.

|

|

418

|

Honorius granted federate status to the Visigoths and they settled in Aquitaine. He could not conquer them, so had to live with them, and in practice they became a separate kingdom under the emperor. The Burgundians followed suit with their own kingdom. Independence was breaking out throughout the empire.

|

|

423

|

Back in Rome, Honorius lived until 423, and his dynasty survived when his sisters' son, Valentinian III took over.

|

|

Hertismere School, Eye

|

|

425

|

Vortigern, a Welsh follower of the Pelagian doctrine, is said to have come to power. The north still had its static Roman army installations and many of the forts were still manned for many years later. He immediately faced the threat of further attacks by Picts down the Yorkshire coast, and the Irish in the Severn Valley.

Between May and October 2007, Suffolk County Council Archaeological

Service uncovered a previously unknown Early Anglo-Saxon settlement lying

across 12 acres (4.72ha) earmarked for new playing fields at Hartismere

School in Eye. It had a continental long-house of a type hitherto unknown

in England. It had a very early cremation cemetery which was eventually dated to 425. The site is extensive but only sparsely occupied, with only 18 SFB s found and identified by 2013. However, the area covered makes it the largest early Anglo-Saxon dig ever undertaken. Bronze Age and Iron Age remains were also found here that indicate a very long history of human usage of this area.

The site was on a tributary of the River Dove which confirmed the known preference of the early Anglo-Saxons for the river valleys of East Anglia, over the claylands of more elevated areas.

|

|

428

|

The British appealed to Rome for help to defend themselves, but no help was available.

So the Council met under Vortigern and decided to appeal to the 'Nobles of Anglekin' for aid. They intended to hire some Saxon seamen to defend the coasts just as past Roman emperors had done. The Saxon leaders were Hengest and Horsa, and three keels or ships were sent with them and they were based on the Isle of Thanet. There were probably only a few hundred of them at this time. They were paid by a monthly system of supplies.

|

|

429

|

With papal approval, the Bishops of Gaul sent Bishop Germanus of Auxerre and Lupus of Troyes to Britain to combat the Pelagian heresy of Vortigern and his people. During the Bishops' visit, the pagan Saxons and Picts made a joint campaign against the British, possibly in Wales where they might have joined the locally settled Irish. Bishop Germanus led the army and was said to have had the victory 'without the might of men,' shouts of Allelulia apparently being enough to frighten the Saxons away. This victory led to the establishment of the British Kingdom of Powys.

Notwithstanding this battle with paganism, Germanus found British Christianity still largely orthodox. He visited St Alban's tomb at Verulamium, leaving behind some precious relics, and healed the daughter of a Tribune. Roman ways were continuing in the central and western areas, although we believe that these ways were lost much sooner in the east. This is explained because it was where the Saxons were more numerous, being the first point to be reached from their ports on the Elbe and Weser Rivers.

|

|

Runic gaming counter |

|

430

|

After a short time the number of Saxons allowed to settle increased and new areas were penetrated. Very early remains have been found at Caistor by Norwich, Luton and Abingdon. This roe deer foot bone was excavated at Caistor by Norwich, and was used as a gaming counter. The runic inscription indicates that it was of north german origin, showing evidence of the new language penetrating British life. The runes spell "raihan", meaning roe deer, and such cryptic inscriptions typify the earliest runes found in this country. This small piece of bone may, in fact, carry the earliest known use of runes in Britain.

These were strategic defensive settlements, established to protect the Cotswold heartlands, and Norfolk was particularly well settled. Because the north still had the army in place, there was less need for reinforcements to be sent there. Forces were placed to protect the North road, the Thames estuary and the major intersections of the Icknield Way. These inland posts were really a defence line of last resort.

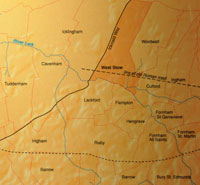

One of these posts might have been at West Stow, sitting on the River Lark crossing of the Icknield Way.

A sprawling half mile long Romano-British settlement known as Camborito had been long established at adjacent Icklingham, and a Roman villa has also been identified there. Finds have been made here over many years and four lead water tanks have now been discovered in Icklingham bearing Christian symbols. In 1974 an apparently Christian cemetery was found with a possible Christian chapel.

Around this time it thus appears that the Anglo-Saxon village Stowa was first established just the other side of the Icknield Way from Camborito. How they interacted and how relations changed over the next 50 years we do not know. The Romano-British were Christian at this time and the Anglo-Saxons were pagans.

In the east and south, Germanic forces were accepted nearly everywhere, with the exception of Verulamium, the capital of the Catevellauni.

In the absence of a Pictish or Irish attack, the Kentish Chronicle reported that Hengest and Vortigern invited reinforcements under Octha to bring 40 ships over to attack the Picts on their own territory. They plundered the Orkneys and then settled in North Northumberland. They may have founded Dumfries - the home of the Friesians. Scotland never tried to invade England again until 1745.

|

|

431

|

The Pope sent Palladius to Britain to convert the Irish but he returned after a few months and died.

|

|

432

|

Palladius was replaced by Patrick, a British monk trained in Germanus' monastery, and later to become St Patrick.

|

|

433

|

The Irish Annals record the first Saxon raid on Ireland which could have been Hengest's warning to leave Britain alone, now it was protected by him. Equally this may have been other Saxons, not under Hengest, continuing their old ways, but they would be a long way from friendly harbours. In any event, the Irish ceased to be a problem until the end of the century.

St Patrick also succeeded in getting the Irish to accept the Roman religion of Christianity. It could be that the Bishops should again be credited with a bloodless victory, this time over the Irish.

|

|

430's

|

Cunedda, or Kenneth of the Votadini, now led a move into Wales from the North of Hadrians Wall, and expelled he Irish settlers with enormous slaughter while the Irish kings stood neutral. This action probably occupied the next 80 years.

Similarly the Cornovii were moved into Devon and Cornwall to expel Irish settlers in those areas.

|

|

437

|

By these means, Vortigern produced a prosperous Britain, with secure borders, only to be overthrown by civil war when Ambrosius saw his chance. With peace, the taxpayers began to refuse to pay for the Saxon defence and the Council tried to send them home.

In 437 it appears there was a battle between Ambrosius and Vortigern possibly at Wallop in Hampshire.

Vortigern had to rely on bringing in a further 19 ships of Saxon reinforcements to defend himself against Ambrosius. They seem to have been settled, together with later arrivals, in and around Canterbury and East Kent.

|

|

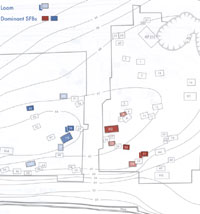

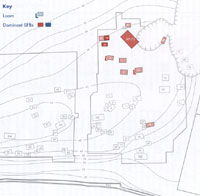

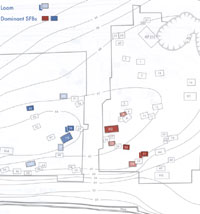

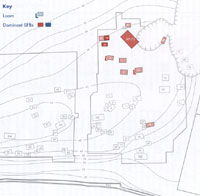

Two family groups at West Stow |

|

440

|

In his book "West Stow Revisited" (2001) Dr Stanley West explained his views of the chronology of buildings at West Stow. He believed that from c440 AD to c480 AD there were these two family groups of buildings located at the site at West Stow. The buildings marked in blue were located around the hall which he referred to as H3. The dwellings marked in red were associated around hall reference H2. The dwellings marked in red on the plan are basically in the area where the reconstructed village was built in the years after 1973. The gap between the two groups has not been excavated because of the 19th century tree belt which now bisects the knoll on which the village stood.

Contour lines outline the knoll on which the village stood. The whole settlement would extend to about 5 acres over its two centuries of existence, and the knoll stood at up to 15 feet above the surrounding ground level.

|

|

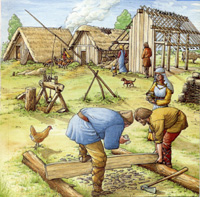

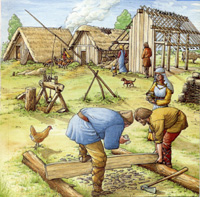

Anglo Saxon Village |

|

blank |

By 440 we believe that the village at West Stow was now well under occupation by the early Anglo-Saxon settlers.

What was it like here when the Anglo-Saxons arrived? There was a 'managed' landscape with Romano-British field systems; grazing for sheep on higher ground, water meadows and arable land all rather run down, as the economy collapsed.

Useful timber for building was to hand, and there were deserted sites, like the Icklingham Roman town nearby, where all kinds of useful things could be found and recycled such as tiles for hearths, bronze, iron and even bits of pottery.

It is believed that many of the Romano-British population survived the collapse of Roman Britain and were absorbed into early Anglo-Saxon society, some at least, as slaves.

There were no forests of pine trees - these are all 19th-20th Century plantations.

From about 440 AD for the next 200 years into the 7th Century the landscape in our area was settled by the Anglo-Saxons, whose little villages controlled areas of land which were to become the 'parishes' of later saxon and medieval times.

West Stow, sitting in the centre of the Lark Valley, was one of a number of similar 'villages' extending from the three round the later Bury St Edmunds to Mildenhall on the fen edge. The Blackbourn valley to the north-east has a similar distribution of sites. They are spaced out along the river banks with territories extending behind. Beyond these settled valleys, central Suffolk, a region of heavy, damp clay was returning to dense scrub and forest after the collapse of Roman settlement. This area was not occupied by the earliest Anglo-Saxon settlers. To the east, settlement penetrated the lighter sandlings of the coastal region much as in the west. To the west and south the river systems of Cambridgeshire were densely settled by Anglo-Saxons and were clearly related by their possessions to those in Suffolk.

Connections were maintained with the continent and Scandinavia with the import of articles of dress and fashion as well as technologies and art.

|

|

Anglo Saxon 'keel' |

|

442

|

More and more boats were arriving from the Continent. There was pressure on the Saxon's homelands from new settlers from Denmark and Holstein, and flooding from the rising sea levels. One such boat, constructed of larchwood, was found buried at Ashby Dell in Suffolk in 1830, a few miles from Burgh Castle. It may have arrived there at a time when the valley was actually a waterway, for sealevel was rising during the 5th century. Its construction is similar to the Nydam boat, excavated in Denmark. A reproduction of the Nydam vessel is shown here.

Hengest's Saxon forces had now increased to such a level that resentment over their spread and their pay rose high on both sides. Hengest demanded more money and more land for his growing forces. Whatever happened, it became a fight and armed Saxon insurrection swept across the lowlands. Vortigern was first driven out of Kent by Hengest.

Later, Caistor by Norwich for example, was totally destroyed as undoubtedly were other settlements, and Colchester was stormed. The economy was also destroyed. The pottery industry ceased production. Farms ceased to produce food, and markets ceased to operate. Certainly Kent and East Anglia were conquered in this first attack. Over the next twenty years conflict would continue between the Roman Britons and the new English peoples. As Britain passed into Saxon control, it would end with much of the Southern British people emigrating to Gaul in the 460's.

|

|

446

|

The Romano-British appealed for help to Gaul, the great General Aetius, and said they were being pushed out by barbarians, and also suffering from widespread flooding. This letter has been called "The Groans of the British". The Saxons attacked right across to the West, but appeared to withdraw to their eastern settlements again after great destruction of the economy.

Aetius provided no help, but Bishop Germanus visited the British for a second time, so we can envisage the country more or less partitioned into Saxon control and old British control with a largely Romanised flavour. Germanus was still attacking the Pelagian heresy, including Vortigern himself by this time, so Vortigern's grip was now loosened and other local rulers had set themselves up in the British areas.

|

|

449

|

This is the year in which Bede placed the invitation of the Saxons to settle in return for defence of Britain. He also condensed most of the story from 428 to 449 into this one year, probably based on his reading of Gildas. In any event, it is still a pretty accurate date by which the Saxons had taken over much of the country.

|

|

Anglo Saxon settlers |

|

450

|

For the next hundred years it seems likely that more settlers from northern Europe moved into Britain. These people did not use coinage as money, but often collected coins made in Gaul, Spain or Italy. By 450 the continent had abandoned silver and bronze as coinage, and all coins were now being made of gold. These were the 4.5 gramme solidus and the 1.3 gramme tremissis, which was worth one-third of a solidus. These coins were also brought into Britain, but were more often than not pierced and used as jewellery. Not until about 575 would the Anglo-Saxons start to use coins as money and a medium of exchange.

How long after the Romans left before the Anglo-Saxons began to settle around Haverhill is not, as yet, possible to determine but we do know where they started; not on the more agreeable south-eastern slope of the main valley, but at the head of the smaller one. The reason was probably that this was a better defensive position. The name Burton means 'the farm by the fort'. So it was at what is now Burton End that they built their fortified farm, on the place which is now called the 'Castle'.

It is thought that the crossroads where Clements Lane crosses Camps Road into Crowland Road probably formed the centre of the Saxon town. The Church stood on this junction to the north-west of the Burton End side.

|

|

452

|

Around this time the British launched a counter-attack upon the Saxon encroachments.

Vortigern's son, Vortimer, was said by the Kentish Chronicle to have driven the Saxons out of Kent and back to Thanet for five years. The main battle seems to have been at Richborough.

The British also won at the Battle of Aylsford, but at Crayford the Saxons won and drove the British out of Kent, back to London.

The Saxons now "summon keels full of vast numbers of warriors" to give reinforcements in what was to become full scale warfare.

|

|

455

|

The British King Vortigern and the Saxons agreed to meet to consider making peace on existing boundaries. Vortigern had lost any authority over the western areas and was too weak to fight the Saxons without total national support and resources. So Vortigern and 300 elders of his Council held a peace conference with Hengest. The Saxons killed them all, except the King, at the table. He was forced to give them Sussex and Essex in return for his life.

|

|

455

|

Back in Rome, Valentinian III was murdered a year after he had murdered General Aetius, and with him died the prestige of his dynasty.

The King of the Vandals, called Genseric, now entered Rome and for two weeks stripped it of all its treasure, carrying it off to North Africa.

This event is generally reckoned as signifying the final fall of the western Roman empire and it "had no strength to rise again." Britain could expect nothing more from Rome, and its only hope for help against the Saxon invaders was to appeal to Gaul.

|

|

458

|

From their bases in Kent, Norfolk and the Cambridge-Newmarket region the Saxons attacked the rest of Britain in a great raid as far as Wales. London remained in British hands. By now, many Saxon villages were at least 20 years old and the young men were born in this country and were in effect fighting for their homes and families, not considering themselves invaders.

|

|

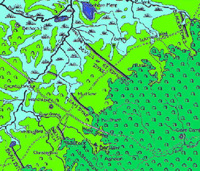

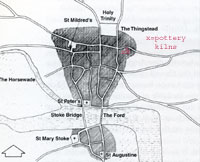

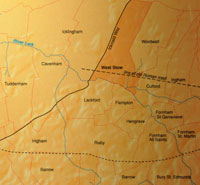

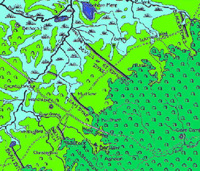

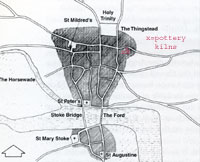

Parishes on River Lark |

|

460

|

The Lark, Blackbourne and Ouse valleys of West Suffolk had been settled by these mixed Angles, Saxons and Friesians by this time, including at West Stow. The village at West Stow was extensively excavated by Dr Stanley West from 1965 until 1972 as the site was under threat from the advancing landfill site established on the former West Stow Sewage Works. In 1973 a programme of reconstruction of some of the buildings of the original village was begun. By 1979 the landfill site was landscaped over, and this experimental reconstruction has continued ever since. An Anglo-Saxon Study Centre has been established next to the reconstructed village which is now included within West Stow Country Park. The West Stow Anglo - Saxon Village is fully explored in this appendix to this Chronicle:

The Anglo-Saxons in St Edmundsbury

The village of Stowa, as we call it today, was located on a small hillock by the River Lark, on very light sandy soil. The Icknield Way crossed the River Lark at a ford a few yards away, running roughly north and southwards. An old Roman road ran east and westwards a few yards north of the village. This road led to the old Romano British village of Camborito, just a few hundred yards to the west. The village cemetery was just across the Roman road.

At first the people of Stowa were cremated when they died and it is estimated that a thousand cremations were held here, of which about 530 were contained in funerary urns.

The Central Suffolk clay soils do not seem to have attracted the Anglo-Saxons. They preferred the river valleys, and more easily worked soils. Other settlements have been excavated at Honington and Grimstone End in Pakenham. We do not know exactly when Bury or Haverhill were first settled by Anglo-Saxons, but we have a better idea of where it took place. In Haverhill the first settlement was at Burton End. In modern Bury we have evidence of several Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, so there were probably at least four small villages within the area of today's town. One was probably where the Abbey's ruins remain today, one near Barons Road, one at Westgarth Gardens and one near Northumberland Avenue.

It seems that the settlers in West Suffolk were based along the river valleys which flowed into the Fens, and that they looked to trade in that direction rather than to the east. It seems likely that West suffolk was thus settled from the direction of the Wash, through the Fens, while East Suffolk was settled up the river valleys like the Gipping, Stour and Waveney, which all flowed eastwards towards the North Sea.

These early Saxon settlements in West Suffolk divided up the land in a way which is believed to be reflected in the much later ecclesiastical parishes. In many places they seemed to have adopted boundaries already in place from earlier times.

|

|

460's

|

Much of the British forces now emigrated to Armorica, later to become known as Brittany. They were not just fleeing the Saxons, they were joining the still Romanised dominions of Aegidius, who needed help to defend Gaul and themselves against the pagan Saxons.

They were given lands North of the Loire and the place name Bretteville is still widespread today in Normandy. These people looked on themselves as Roman provincials and had little difficulty moving from one part of the old empire to another. They were well educated and Gildas complains that all the books were taken out of Britain with them. They made a fighting force of about 12,000 to reinforce Aegidius.

|

|

460's

|

Despite the emigrations to Gaul, the Roman Britons continued to resist the English spread, perhaps up to about 495.

Although Vortigern had ceded Sussex, it was not taken unopposed. Aelle landed at Selsey Bill to take Chichester but was thwarted. London, Chichester and Verulamium were still in British hands but 12,000 troops had gone to Armorica so a decisive counter attack was ruled out. However, various local leaders or Kings took various offensive actions to avoid their own total destruction. Ambrosius Aurelianus, perhaps one of the last of the aristocratic Roman nobility to survive, was a central British figure of these battles. Ambrosius led the resistance for the early years of this 30 or 35 years action.

|

|

476

|

In Rome, Odovacer discontinued the nomination of western Roman Emperors, and turned to Constantinople.

|

|

470's

|

Ambrosius Aurelianus was succeeded as the main leader of the surviving Romano-Britons by Artorius, another man of Roman family, known to us today as King Arthur. This is the real period of Arthur, a relic of the fallen Roman Empire, hanging on against the Saxons constantly encroaching from their new homelands in East Anglia. The British retained a knowledge of literacy, and of Christianity, whereas the Saxons must have seemed totally alien, with their pagan practices, and contempt for books and the ways of "civilisation". This scene must have been very different from the romance of Knights in shining armour which arose in Medieval story telling, maybe 600 to 700 years later.

It seems likely that British resistance in 470 was based on the wealthy farmlands of the Cotswold area, Salisbury Plain and in Hampshire. It is also highly possible that they based their tactics upon the use of horses and mounted cavalry. This knowledge may have been remembered from Roman days, or invented by necessity, but their armour and weapons would be have been Roman. The Saxons at this time invariably fought with spears on foot, and this helps to explain how the weakened British managed to resist them for so long. Using mounted men in hit and run attacks, they could also cover large amounts of territory at five times the speed of the Saxons. It has been suggested that as the Romano-British did not use stirrups, they could not fight from horseback, but we now know that a saddle can be designed to work without stirrups.

The British cavalry needed secure overnight stops and used the old Roman walled towns, or re-occupied some of the old iron-age hill forts like South Cadbury.

Battles were fought in a zone from Wiltshire and the borders of Gloucestershire up to the Cambridge area. There is no evidence of fighting in the Saxon/English heartlands of Norfolk and North Suffolk or Kent.

The British resistance inspired a new sense of local identity, no longer Roman. They called themselves Combrogi or 'fellow countrymen', whose modern form is Cymry or Cumbri, names which survive today in Wales and Cumbria.

The English knew them by both names, and also called them foreigners or wealh or wylisc in Old English, and Welsh in today's English. The English saw them as part of the old Christian world, based on Rome.

The Anglo-Saxons named their country Englaland (land of the Angles) and their language was called Englisc. It is the modern historian who refers to them as Anglo-Saxons, who spoke Anglo-Saxon or Old English. Suffolk is full of Anglo-Saxon place names, most names coming from Old English words.

Latin writers referred to them as Angli and were doing so before the middle of the 6th century. By the 7th century King Ine called himself King of the West Saxons but described his subjects as Englishmen or Welshmen, but not as Saxons.

Saxon was a term used by foreigners, and survives in modern Welsh as Saesnag and in Irish as Sasenach. Until about 650, the Saxons were Pagan, also called Heathens or Barbarians.

Latin was still the written language of the British, although the need for it rapidly diminished as contact with the Empire declined.

|

|

480

|

At about 480 Cerdic was commander of Saxons in the Winchester - Southampton area. They fought in the Battle of Portsmouth Harbour against Arthur and the British. This was probably at Portchester, the most westerly of the old Saxon-shore forts. The battle seems to have had no decisive outcome.

The flow of immigrants much increased in the late 5th century, to such an extent that the homeland of Angeln was deserted in Schleswig. At this time we believe that the Kings and their courts also moved to England.

In the Ipswich area a group arrived with a strong Scandinavian background, and Danish traces are recognisable in the archaeology of Kent.

|

|

486

|

In Gaul, King Clovis of the Franks killed Syagrius and took over his kingdom. By 507 he drove the Goths out of Aquitaine and occupied Bohemia setting up the framework of France, land of the Franks.

|

|

488

|

In 488 the South Saxons became ruled by Aesc, who inherited the leadership from Hengist. In 491 he led an attack on the old Roman fort at Pevensey, and massacred its entire garrison. Meanwhile Cerdic and Cynric were founding a West Saxon dynasty.

|

|

490's

|

London and its surroundings remained a British stronghold separating the Saxons of Kent from those in East Anglia. This situation seems to have persisted up to 568.

The Saxons themselves were not a homogeneous group. Differing grave goods found in their cemeteries indicate that some settlements contained markedly different cultural backgrounds from others, even when comparatively close to each other. For example, at Haslingfield, a village in sight of Cambridge, these people seem to have had no contacts with Cambridge Saxons. Others of their kind have been found in the Middle Thames area. The Eslinga Saxons may thus have been allies of the British at this time.

|

|

495

|

The final battle of this era was the Battle of Badon Hill (Mons Badonicus according to Gildas). The English King Aelle led the Saxons from Kent, Sussex and Wessex and seems to have advanced westward to attack British cavalry bases. Badon may be at or near today's Bath such as Solsbury Hill by Batheaston, but its exact site is unknown and hotly disputed. According to Nennius, there was a 3 day siege which ended when King Arthur led a charge and killed 960 Saxons. Following victory at the Battle of Badon, won by the British, peace lasted for 75 years.

The difficulty of establishing accurate dating in the 'Dark Ages' is shown by this battle, which some historians date to 516 or 518. It is best thought of as occuring shortly before or after the year 500.

|

|

Gold pendant from Undley |

|

500

|

By now the war in England had been fought to a standstill, with partition of territory being an established fact. Eastern England, and East Anglia in particular, was firmly held in Saxon and Angle hands.

Trade and social contacts were probably maintained with their homelands, as shown by many of the objects that have been found. At Undley, near Lakenheath, a high status Angle wore this gold pendant shown here. It was made in the late 5th century in Schleswig or southern Scandinavia. A roman helmeted head copies many Roman coins, and although the wolf and infants is a strong Roman motif, there are also runic characters present. Such a pendant, made from a pattern stamped into flattened gold, is known as a bracteate.

This object illustrates one of the earliest known examples of runes seen in England. Literacy under the Romans had used the latin alphabet still familiar to us today. The northern German tribes had adopted a runic alphabet, known to us as the "futhark", by the 3rd century AD. This object helps to illustrate their linguistic and cultural penetration into eastern Britain at this time.

Although the British had stemmed the English advance further westwards, the Roman Empire had faded around them, and they had no larger continental Empire to support them. The Romanised economy was destroyed by war, and the British had to rebuild their lives in their own way, with only half the country's resources available to them.

In the Fens the Roman drainage system built around Car Dyke had failed as there was no administration to maintain it against the rising sea levels. Areas of Fen now flooded, leaving only Ely and a few other islands above the water level. Along with this problem came a rise in sea levels through the 4th and 5th centuries, so that by this time East Anglia was a virtual isthmus, cut off from the area of Mercia to the West by the great marshy fenland.

To the south the heavy clay soils of the Stour valley were reverting to Wildwood. The Roman roads were becoming overgrown by impenetrable blackthorn thickets by a lack of use and maintenance. Rome's once great city at Colchester declined into a ghost town by the 6th century, and both Colchester and the area of North Essex would be sparsely populated until the coming of the Danes in the 10th century.

However, for the next 15 years this period was peaceful and was looked on as a golden age of freedom, truth and justice under King Arthur, by Romanised scholars like Gildas. As the Saxons themselves kept no written records their views of the situation are unknown. Welsh poems and later monastic traditions regarded Arthur as a tyrant. Gildas never named Arthur, and the modern legends surrounding King Arthur did not begin until first taken up in Norman France in the 12th century by Chretien de Troyes. The story was taken up by Geoffrey of Monmouth in England shortly afterwards, and Malory's Morte d'Arthur followed in the 15th century.

Arthur continued to experience conflicts such as at Chester and various boarder actions against the Irish in the north west, and in Wales and Cornwall and possibly local rebellions by British war lords. His success led to him being called Emperor and Roman titles and governorships were somewhat restored in the area under his control, based on lowland central England.

There is some evidence that Saxon settlements which were on the fringes of Saxon control, like Kempston by Bedford, were sent packing by Arthur, establishing stricter borders between both populations. Following years of bloodshed and flight to Gaul, it appears that the population in 500 was only a small fraction of what it had been in the Roman period by 400 AD.

Arthur probably held court in each of his cities, such as Chester, York, Gloucester and Colchester. The British name for Colchester was Camulodunum, a possible source for Camalot or Camelot as it is now spelt.

|

|

Anglo Saxon horse burial |

|

510

|

Around 510 a Saxon nobleman was buried with his horse at Eriswell. The site was discovered in 1997 under a baseball pitch scheduled for redevelopment on the USAF base at RAF Lakenheath. Some 200 graves were located on the site, spanning a period of 150 years. This is now a completely different form of burial than the earlier cremations exemplified at West Stow.

Over the next 5 years more graves were discovered. Eriswell had three cemeteries with 446 graves finally identified. This is a major find for East Anglia and covers the 200 year period from the late 5th to early 7th centuries. There were other horse burials found, but the first one in 1997 aroused the most excitement.

Although the remains were originally dated to around 550AD, a radio carbon date was obtained in the early 21st century which placed the first horse burial burial to between 490 and 535AD. I have therefore located it at roughly the midpoint of this range for the purposes of this Chronicle.

The first such horse burial to have been discovered may well have been at Witnesham, near Ipswich, in 1820. This was on the land of the Reverend C Eade of Metfield, farmed by Charles Poppy. The body had a lance and helmet, and the horse had full saddle and harness.

|

|

515

|

King Arthur died at the Battle of Camlann according to the Cambrian Annals. The location of this and its causes remain unknown, but there was no one to take his place as overall Emperor. He was almost the last remainder of the western Roman Empire, outliving even Rome. Some historians date this battle to 537 or 539.

|

|

6th century village life |

|

525

|

By this time it would appear that local tyrants were carving out their own territories, and the generals were growing in power and usurping local government and the judges. This was all in the non-Saxon areas, and we know about it from Gildas.

After this date a further wave of settlers came to East Anglia and Kent from Sweden via Denmark and Friesland. If it was around this time they may have been led by Wehha, because the first King of East Anglia was Wehha according to Nennius, a 9th Century historian.

In 525, the Anno Domini system of dating was invented by Dionysius Exiguus, a Scythian monk living in Italy. This system would be irrelevant in Saxon England until Christianity reappeared after 630.

|

|

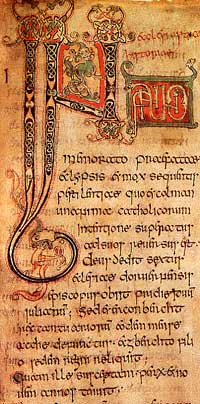

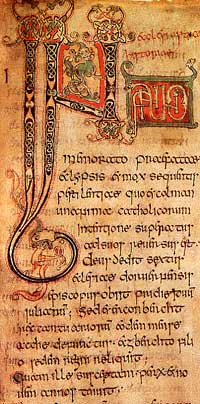

538

|

Around the year 538, Gildas wrote his 'complaining book', which was an attack on the princes and bishops of his day. He tried to look at history to find the origins of the evils he perceived. Gildas was born in the kingdom of the Clyde but was taken south to the shores of the Severn Sea and was taught in the old Roman educational tradition. Gildas tried to explain why the British were being punished by being occupied by Anglo-Saxons and why they deserved this fate. Much of recorded history from 440 to 540 relies upon the work of Gildas, and Bede in 731 repeated Gildas' history. However, it is now thought that from 449 onwards, his dates are about 20 years later than reality.

|

|

540

|

If there were new settlers at this time they presumably were led by Wuffa who would have been the second King after Wehha. He sailed up the Deben to found Ufford and the Wuffinga dynasty. These people had a considerable impact despite the fact they were preceded by 100 years of continental settlement. With a strong maritime tradition they practised ship burials at Sutton Hoo, Snape and Ashby. The descendant royal family is known as the Wuffings or Wuffinga. The dynasty is thought to have continued with Tyttla, and then to Raedwald, the most famous and greatest of them.

The area later known as the Wicklaw, and later as the Liberty of St Etheldreda, may have been the home estates first established by the Wuffing kings. It covers all their major sites from Rendlesham to Sutton Hoo, and the estuaries of the Deben and Alde and south to the Orwell.

By now East Anglia seems to have become one cohesive kingdom. A strong king would be welcome to impose order in the land and to create the stability without which the farmers could not till the land successfully.

In these early times the King would have lived off the proceeds of his own estates. In addition, there arose a system called "food rent" or "feorm", whereby the King was supplied with food and provisions by each group of settlements in some agreed form. This may have arisen as the King moved his entourage around his kingdom, perhaps spending periods at designated royal "vills" or settlements. In the absence of money, these food rents were paid as real provisions. Each settlement also owed their lord a variety of services, mainly a mixture of agricultural and military duties.

|

|

541

|

Dendrochronology is the science surrounding tree rings. By examining the rings which indicate each year's growth we can

identify periods in which trees grew very little or not at all. This is

indicated by clusters of extremely narrow rings, which suggest

extremely cold growing seasons. A band of these narrow rings occurred

after A.D. 540 and lasted about six years in parts of Europe, Asia, and

North America.

It has been suggested by Michael Baillie, Professor of

Palaeoecology at Queen's University, Belfast, that these periods may have been caused by comets or planetary debris which throw dust into the atmosphere, thus causing several cold years, as the sunlight is reduced at the earth's surface.

Exact dating of these early events is difficult and dates get continually adjusted in the light of further evidence.

On 20th November, 2018, the Times newspaper reported the work of Michael McCormick of Harvard University who dated this disaster to 536 AD, based upon the works of Byzantine scholar Procopius. Procopius wrote, "The sun gave forth its light without brightness, like the moon, during this whole year". Irish chronicles noted " a failure of bread from the years 536 - 539. In 541 Bubonic plague killed up to half the population of the eastern Roman Empire. Harvard scholars have linked these events to a volcanic eruption in Iceland that spread a high level layer of ash around the globe. Two more eruptions occurred in 540 and 547. It is suggested that these events caused economic stagnation across Europe lasting for a century.

|

|

547

|

A severe epidemic, possibly of Bubonic Plague, spread in Britain, and seems to have lasted until 551. This was called the Yellow Plague, which spread thoughout most of the known world, killing millions of people.

|

|

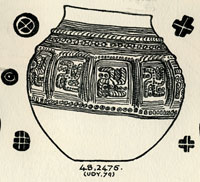

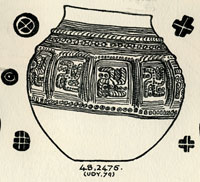

Pots from graves Eriswell |

|

550

|

These hand-made,highly decorated urns are typical of sixth century pottery in England. They were made on a small scale and fired in clamps. These early Anglo-Saxon urns were excavated at Eriswell Anglo-Saxon cemetery. They were not cremation urns, but seem to be grave goods which possibly held food or drink for the afterlife. No kilns were found on site, and many pots have potters' stamps which are also known from West Stow, Lackford and Spong Hill.

|

|

563

|

St Columba founded his monastery on an island called Iona off the west coast of Mull in Scotland. Columba lived from about 521 to 597 and evolved teachings which diverged from European practice, ultimately leading to deep divisions in the church.

By about 560 the era known as the Great Migration period had largely ended. The Yellow Plague may well have helped to end much more movement of populations.

Outside East Anglia, there were the kingdoms of Kent, the Jutes in the Isle of Wight, the East Saxons and the West Saxons. Other Germanic or European kingdoms were established across England by the 7th Century.

|

|

570

|

The second Great Saxon uprising led to the English mastery of the area called England today. The old British way of life, hanging on in the Midlands, was ended when Verulamium (St Albans) and its surrounding parts of the Chilterns were finally conquered by the Anglo-Saxons. It also appears that the British stronghold of London and its surroundings was finally over-run around this time.

The Saxon's pagan culture would be unchallenged in England until about 630, when Christian missionaries started to impress the Saxon kings. However, the pagan culture was itself in a state of evolution. Early on the preferred death ritual was burial of cremated remains in an urn. Burial of the body with grave goods was now more prevalent, and in some high status cases mounds were being thrown up over the grave. The Anglo-Saxons had found many earlier period Bronze Age mounds, and had sometimes used them for their own purposes. At Snape, for example, existing mounds had been used for burials of cremated remains in urns for a century or more. But around this time a remarkable high status burial was carried out in a 14 metre long ship, buried under a large new mound. In 1862 the burial at Snape was excavated by S Davidson and Dr N Hele, who found it already plundered in antiquity. Nevertheless the ship was clearly visible, and was followed by other burials around it.

Near Sutton Hoo, on the River Deben, another cemetery has a mixture of cremations, and inhumations. The cremations are different than at West Stow, with ashes buried without containers, but under mounds. With other indications this is thought to represent Anglian links with the royal family in Kent. Soon, those of the very highest status in the area of Rendlesham, Ufford, Kingston and Sutton, would be buried under large mounds in a new grave area reserved for themselves, which we now know as the barrows of Sutton Hoo.

Meanwhile, any remnants of the old Celtic and Romano-British way of life survived only in areas we refer to today as the 'Celtic Fringe', such as Wales, Cornwall and Ireland. Ireland would become important in future years as one of the bases from which Christianity would return to England.

|

|

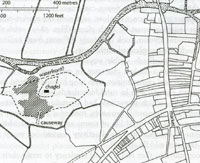

Defensive dykes on Icknield Way |

|

c.575

|

The Devil's Dyke at Newmarket, and the Fleam Dyke, a few miles further to its south west have long been believed by some historians to date from around this time to defend from attack from the west. Recent detailed work has confirmed that these earthworks date from the 5th to the 7th centuries. They are also aligned to face an attack from the south west.

The Devils Dyke is the largest of these works, at over seven miles in length. Today they look like old railway embankments, and the work needed in their construction must have been similar. The Victorians needed a thousand men to build one mile of embankment in a year, and this scale of effort would have been needed by the Anglo Saxons for seven years in the construction of Devils Dyke. Only a great king of a prosperous nation could undertake such a feat of engineering.

Previously, some had claimed that, on the contrary, they were thrown up earlier by the British to stem the Saxon advances. In practice they may have been used, reused, and modified by successive generations. There are other earthworks within the area of the East Anglian kingdom, such as Black Ditches on Cavenham Heath and Risby in Suffolk, and the War Banks at Lawshall. These may have more obscure origins.

|

|

576

|

By about 575 AD the Anglo-Saxons in England began to understand the use of coins as money. The continental gold solidus and tremissis had long been known in England, but for decades had mostly been used as jewellery. These gold coins were of high value, and thus not for use in everyday transactions, but they could be given as part of large land transaction or marriage settlement. Merovingian coins from Frankia were not unusual in England at this time.

|

|

c.577

|

Bath, Cirencester and Gloucester were taken by the Saxons and the West Welsh became isolated.

|

|

578

|

Roger of Wendover, writing in about 1235, recorded that Tyttla now ruled over East Anglia, presumably following the demise of Wuffa. Bede, in about the 720's, also noted Tyttla as the father of Raedwald and Enni. Wuffa himself may have been one of the very first to be buried under a mound at the newly founded aristocratic grave site now known as Sutton Hoo.

|

|

580

|

In 580 or a short time before, King Aethelberht of Kent married Bercta, or Bertha, the daughter of the Frankish King, Charibert of Paris. This gave Aethelberht a degree of power and prestige over those Franks who had settled in Southern England. He would grow to dominate the whole of the south following this dynastic alliance.

In return, Aethelberht agreed that Bercta could continue to worship in her Christian faith. Most of the kingdoms just across the Channel from England were Christian, and the English kings would have been well aware of that religion, even if they kept their own traditional beliefs.

As ties grew with the continent it is not surprising that late in the 6th century Merovingian Frankish gold coins reached our shores and a purse of such coins was found at Sutton Hoo. No Anglo-Saxon native coinage existed at this time.

|

|

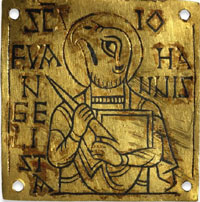

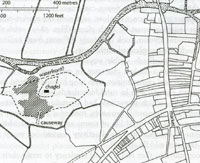

Lackford Cremation Urn & potmarks

|

|

585

|

In 1947 T C Lethbridge excavated a pagan Saxon cemetery at Mill Heath, Lackford. The site is above the 50 foot contour on a peninsula of land between the south bank of the River Lark and the Cavenham Mill stream. He found between 400 and 500 cremation urns, a concentration which is unusual for the Lark Valley, where earth burials, or inhumations, are more prevalent. There were swastikas present upon a number of cremation urns, and the Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Lackford has yielded some of the most exquisite designs of this image.

|

|

Lackford funerary urns

|

|

blank |

These urns were also important because they confirmed in some cases the identification of individual potters. Lethbridge called some of the pottery the Icklingham type, as he assumed that Anglo-Saxon potters had used the same local clay as had the Romano-British potters who had left kilns at Icklingham and on West Stow Heath. For some years the Icklingham potter has also been identified as the Illington/Lackford potter. He has been known to have working during the late-sixth century somewhere along the west Norfolk/west Suffolk borders. His output was cinerary urns of a number of standard types decorated in two or three routine styles. Decoration was stamped on to the vessels while they were still damp. One of these stamps has been found and it was made out of a red-deer antler and bore a cross die. Stamps frequently used by the potter, or potters, were a cross-in-circle, a St Andrew’s cross and a concentric circle with a blob centre. Decoration in the main was restricted to pots used as cinerary urns. Distribution of the products was roughly within a radius of some thirty miles centred on Lackford with one outlying example some eighteen miles further on at Castle Acre in Norfolk.

|

|

590

|

In Rome, Gregory had been Prefect since 583, and in 590 he became Pope. In the 570s he was said to have seen English slaves for sale in Rome, and determined to convert the English to Christianity. He decided to contact Bercta, the Frankish Christian wife of Aethelberht of Kent, to seek assistance to send a mission to the English. He resolved to send Augustine, the Prior of Gregory's new monastery of St Andrew, in Rome, to lead the mission. After a few false starts, Augustine would reach England by 597.

Also in about 590 the first Anglo-Saxon coin was struck in Canterbury, making it the earliest to be minted in England since Roman times.

|

|

Glass beaker-Westgarth Gardens

|

|

blank |

By this time the settlements like West Stow were long established. Nearby at Lackford a large cemetery of several hundred cremations in globular urns has been excavated. West Stow had its own burial cemetery. It has been thought that by now the custom of cremating human remains and burying the ashes in a funeral urn may have been replaced by burial of the body. Lethbridge believed that this was not so, and that cremation continued until the Christian era after about 650.

Many more cemeteries have been found than settlements, simply because human remains and grave goods have been more easily identified than the soil marks remaining from decayed dwellings. Thus we know of cemeteries in Bury at Northumberland Avenue, Barons Road and Westgarth Gardens, but do not know where their settlements lay.

|

|

597

|

Columba of Iona died in this year, but Christianity now had another advocate in the south.

Augustine finally arrived in Kent on his mission from the Pope. He was met by King Aethelberht on the Isle of Thanet, where Aethelbert had given them permission to land. This seems to have resulted from Athelbert of Kent being married to Bercta, or Bertha, his Frankish princess from Northern Gaul, who was a Christian. She was asked by Pope Gregory to use her influence on the King and paved the way for Augustine.

At first Aethelbert confined the Christians to Thanet, and when he did meet them, he travelled to the Island himself, rather than summoning them to his own halls. He spoke to them out of doors, a position which Bede said was to avoid the possibility of witchcraft.

Aethelbert, at first, refused to accept the Christian message, but he permitted them to preach throughout Kent, and soon allowed them to set up home in Canterbury, where the King himself lived with his Christian wife, Bercta.

Augustine and his entourage began to build and restore the remnants of Roman churches, and began to convert the population of Kent to the Roman form of Christianity. He brought 40 monks with him and at Christmas 597 some 10,000 people were baptised in Kent. Canterbury would become the home of English Christianity from this beginning.

Athelbert was rising to become High King of England and political refugees seem to have been accepted at his court, including Raedwald, later to be King of East Anglia. Raedwald possibly converted to Christianity in Kent at this time. Politics at this time was sometimes a violent power struggle and those on the losing side often fled to other kingdoms. In this respect the Anglo-Saxons were much like the Romans.

|

|

How Raedwald may have looked |

|

599

|

With Christianity rapidly being adopted in Kent, and Aethelbert of Kent rising in power beyond his Kentish borders, Tyttla of East Anglia died.

The mighty Raedwald returned to East Anglia and took over his Wuffing inheritance as their king and seems to have ruled over all East Anglia. Bede recorded that Raedwald ruled East Anglia from Rendlesham in East Suffolk.

He now married a royal bride, whose name we do not know, but she had been married to an East Saxon prince, and already had a son of royal blood, called Sigeberht.

The royal cemetery was nearby at Sutton Hoo but was unrecorded until its first excavation in 1939. Raedwald's first act may have been to oversee a lavish burial of Tyttla at Sutton Hoo.

|

|

Wuffing kingdom of East Anglia |

|

600

|

By this time, the East Anglian kingdom of the Wuffinga dynasty was independent, powerful and economically successful. But the threat from Mercia in the west was increasing. Gipeswic, or Ipswich, was probably set up as a trading post around 600, and would quickly develop through the century, becoming a major port and industrial centre. Raedwald may have been involved in establishing Ipswich.

The 7th century had three great characteristics, not seen before in Anglo-Saxon England. These were:

- (a) the consolidation of the countryside into Kingdoms, ruled by a king of a 'royal' family;

- (b) the introduction and spread of Christianity, which had died out after the Romans had left; and

- (c) the rise of towns again for the first time since the Roman withdrawal.

These changes, which took place over the 100 years of the 7th century, changed Anglo-Saxon England beyond recognition. The economy changed with the development of trade and the introduction of urban life. Christianity brought new patterns of thought, literacy and the facility to keep records and write down history. The King and his court exercised more and more authority over everybody's lives.

As time passed the system of government became more formalised. The way in which the king received his "feorm" or food rent was, no doubt, refined by local moots or councils. The military service owed to the local lord and to the king was also refined, so that each district had to find a specified number of fighting men for the "fyrd", or military levy. These duties would require areas to be grouped together in some formal manner, which would later evolve into the "Hundreds", which survived as units of local government into modern times.

|

|

601

|

By 601 King Aethelbert of Kent had accepted Christianity as his personal religion, along with many of his Kent subjects. In 601 Pope Gregory wrote to him to "hasten to instil the knowledge of one God, father, Son and Holy Spirit, into the kings and nations subject to you."

The Pope is clearly acknowledging Aethelbert's position of High King over much of Britain, as well as encouraging him to recruit them to Christianity.

|

|

603

|

Aethelfrith of Northumbria defeated Aeden, King of the Scots. He was gaining power in the north, while Aethelbert was growing in power in the south.

The Welsh bishops rejected Augustine's teachings, preferring to retain their own Irish form of Christianity.

|

|

604

|

According to Bede, it was in the year 604 that King Raedwald of East Anglia converted to Christianity.

By at least 601 King Aethelbert himself had converted to Christianity and he wanted his allies to join him. Both Saeberht of the East Saxons and Raedwald cemented their relationship with the Bretwalda Aethelbert, by travelling to Kent to be baptised and to take Holy Communion. St Augustine himself may have baptised Raedwald in Canterbury. Augustine also consecrated Mellitus as the first Bishop of London, with his seat at St Paul's, to minister to the East Saxons. It seems likely that Augustine would have wanted to appoint a Bishop into Raedwald's East Anglian realm as well. Perhaps Raedwald was not ready to accept such a posting at this time.

Raedwald was to become notable because he would set up a pagan altar and a Christian altar within one temple at his home, and seems to have trodden his own fine line between the old religion and the new. After all, Pope Gregory himself had advised Augustine not to destroy existing pagan temples, but to convert them to Christian worship. Bede recorded that it was Raedwald's new pagan wife who led him astray from Christianity. Probably it would have been politically necessary for a new king of a pagan people to pay some regard to their existing beliefs and sensibilities.

In any case, Raedwald's Christianity was the first to be established north of the Thames, and despite his temple of two altars, Christianity would become the established religion for the future.

|

|

605

|

Raedwald of East Anglia and his new wife had two sons together, named Raegenhere and Eorpwald. Raedwald's wife had another son, called Sigeberht, by her first husband. Sigerberht seems to have spent much of his life in Gaul once Raedwald had his own heir, where he was safe from Raedwald.

At about this time King Aethelbert of Kent produced the first written Code of English Law. Basically it was a list of the amounts of compensation payable for various crimes. These amounts were by no means equal justice for all. Aethelbert defined the classes of society, and each class got a different level of compensation. The classes presumably reflected the social realities of the time, and were divided as follows:

- The King

- Earls

- Freemen

- Churls

- Bondsmen

- Slaves

The church had ensured its place in this code. If anyone stole the property of God and the Church the compensation was to be twelvefold. Stealing from a Bishop brought elevenfold compensation, a priest ninefold, and so on down to a cleric who got threefold compensation.

There were about 90 crimes described between different classes of person, and how much each was to be paid for.

St Augustine would have advised the king on these laws, but he was to die in 605. The second Archbishop of Canterbury was Laurence, who had accompanied Augustine from Rome.

|

|

Rough cut garnet beads |

|

615

|

Although we may picture the early Anglo-Saxon period as a time when subsistence farmers led an isolated and bleak existence, there are many archaeological finds which led us to believe that early life was not without its pleasures and delights. Neither was early England cut off from the rest of the world. Objects from distant lands tell us that trade routes reached into the Far East, such as these garnet beads which were very likely originally from Sri-Lanka. These rough cut beads may have been intended for further cutting and processing, but have instead been used as unfinished beads, perhaps because they were of a lesser quality than required for the best work. These beads came from the Aldeborough area and were sold on E-Bay in 2012.

|

|

616

|

The High King of the South was acknowledged to be King Aethelbert of Kent. However, on 24th February in 616, he died after a reign of 56 years, according to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle. He was succeeded by his son Eadbald, but Eadbald was not a baptised Christian. In itself this need not have prevented a conversion, but he decided to adopt the old custom of marrying the wife of the old king. As she was also his stepmother, the Christian church viewed this as incest under a ruling by Pope Gregory, and the marriage must have horrified Archbishop Laurence of Canterbury as much as it re-assured the still pagan rural population. The mission to Kent must have been very shaky at this point.

Around the same time the old Christian King Saebert of the East saxons also died. He is a strong contender for the royal person who was buried in a rich and elaborate grave chamber at Prittlewell in Essex. Now located in the suburbs of Southend, this was a strategic port on the River Thames.

King Saebert of Essex had three pagan sons who now demanded to take communion as their father had done. Bishop Mellitus of London had to refuse as they were not baptised, and the result of a seemingly minor disagreement was that Mellitus and his Christian mission was "out a-shoved" from Essex. In this case it would be several decades before Christianity returned to the East Saxons. Mellitus had to go to Canterbury.

Aethelfrith of Northumbria had recently defeated the King of Scotland. In 616 he also defeated the Welsh at Chester, isolating Wales. Bede saw this as a punishment from God, because the Welsh would not adopt Roman ideas about religious practices, including the date of Easter. However, the increasing power of Aethelfrith now threatened the other kings of the south, particularly Raedwald. As Christianity had still not reached Aethelfrith, it meant that his rise must have also threatened the future of that religion in England.

By the end of the year it must have seemed that Christianity was in full retreat in England. Only King Raedwald with his two altars was still ruling as a Christian King. Archbishop Laurence, Bishop Mellitus and Bishop Justus of Rochester now decided to abandon their mission to Britain, according to Bede. Apparently they did not leave, and Bede also recorded that it was the example of Raedwald that eventually would bring King Eadbald, and his kingdom of Kent back into the Christian fold.

|

|

Possible Hall at Rendlesham |

|

617

|

Since about 590 King Aethelfrith of Northumbria had been expanding his realm. He had conquered the Scots and the Welsh from his stronghold at Bamburgh Rock. By marrying the Princess Acha of Deira, he had extended his reach southwards into modern Yorkshire. He had driven out Acha's brother Eadwine, first into Mercia, then into East Anglia.

Eadwine or Edwin was thus a claimant to the throne of Northumbria, and to escape reprisals had finally sought safe shelter at the court of Raedwald. He was welcomed as an honoured guest in Raedwald's Hall at Rendlesham. The Hall at Rendlesham has never been found, but this illustration from Sutton Hoo Centre suggests how it might have appeared. Although Aedwine was far away from Northumbria, Aethelfrith could not accept Aedwine on the scene, however far off.

Aethelfrith therefore tried to bribe Raedwald with two offers of great wealth to kill Edwin to remove him as a rival. Raedwald refused to kill Edwin, and Aethelfrith then offered even more, together with the threat of war if his wishes were again refused. Bede tells this story together with tales of mysterious visitors who come at night to make offers to help Aedwine to escape, and to give him advice. This may all be linked to the view that while he had been in East Anglia, Edwin was converted to Christianity by Paulinus, who was a part of Augustine's mission to Canterbury. Part of the arrangements made to support Aedwine might have included the condition that he had to convert to Christianity.

Bede claimed that Raedwald had finally decided to betray Aedwine, but was persuaded by his Queen that no amount of gold would counterbalance the dishonour such a betrayal would mean. War with Northumbria was now inevitable, not only because of Aedwine, but because of the power struggle between two great kings for overall mastery of the country.

Raedwald did not wait for Aethelfrith to carry out his threat of war. Instead, he went on the offensive and led his army north as far as the River Idle, south east of Doncaster, on the southern edge of Aethelfrith's kingdom.

Raedwald's army was in three columns, and the Northumbrians managed to destroy one column, killing Raedwald's son in the process. The other columns, led by Raedwald, stood firm against Aethelfrith and finally defeated his army after killing him.

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle recorded this event many years later as follows:

.

"Here Aethelfrith, king of the Northumbrians, was killed by Raedwald, king of the East Anglians, and was succeeded by Eadwine."

This battle gave Raedwald enormous new power in the country, although his son, Raegenhere was killed in the process. Edwin was given Northumbria as a client king of Raedwald. As the old King of Kent, Ethelbert, had died the year before, Raedwald was now acknowledged as the English Bretwalda. This meant he was the High King, with his power extending even into Northumbria. No previous English King had been so powerful, and the message would have been clear, that Christianity included success in battle.

|

|

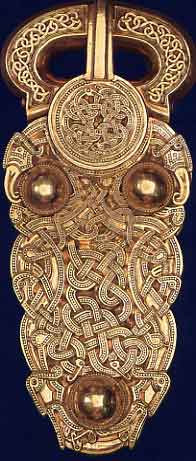

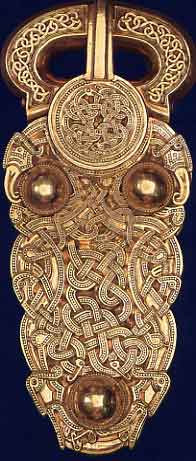

Sutton Hoo epaulette |

|

618

|

Raedwald was a Wuffing, and part of the Wuffing prestige was to link their family origins to Odin and to Caesar. This claimed link to a Roman Emperor may help to explain some of the objects found in the royal grave at Sutton Hoo. These shoulder clasps were directly reminiscent of the epaulettes worn by Roman Officers, and the show of wealth and power which they embodied would strengthen Raedwald's claim to overlordship of Britain.

Following the battle on the River Idle and Raedwald becoming acknowledged as Bretwalda, it is likely that this victory would have inspired other kingdoms to adopt or re-adopt the new Christian religion. At some point the new King of Kent, Eadbald decided to accept baptism, and Canterbury became re-established as a Christian centre. Its future had been in grave doubt after the christian King Aethelbert of Kent died early in 616 to be replaced by his pagan son Eadbald. In addition, Saebert of the East Saxons had also died in 616, and Bishop Mellitus had been sent packing from London.

|

|

622

|

Meanwhile, far away at the eastern end of the old Roman Empire, the Prophet Mohammed escaped from Mecca, and began to impart his message around Persia, which had temporarily conquered Constantinople, Jerusalem and Egypt under the Zoroastrian King Chosroes II.

|

|

Sutton Hoo gold buckle |

|

625

|

Around 624 or 625, Raedwald, the High King of the East Angles, must have died, although we have no written evidence for this. After the battle on the River Idle, Bede gives Raedwald no further space. Raedwald was the greatest of the Wuffinga kings, and it is generally accepted that he was buried in a pagan ship burial at Sutton Hoo, in great splendour.

However, this is not the whole story. Raedwald knew about Christianity, had been baptised and had adopted it, although his burial was basically in the traditional pagan manner of the Wuffings. He was known to have kept a temple with two altars, one for the old gods and one for the new, an arrangement which scandalised Bede. Bede blamed Raedwald's wife for this arrangement as she was thought to always retain her pagan beliefs.

We can accept that Raedwald never actually rejected Christianity, as he was buried with some Christian icons. By his head were two baptismal spoons, engraved Saulos and Paulos, often given to those who had accepted an adult conversion. Cruciform designs are visible on several objects in the grave, including silver bowls. Despite Bede's misgivings from his monastery in Jarrow in a century later, Raedwald probably considered himself a Christian King, and was probably regarded as such by those around him at the time.

The royal treasure of Raedwald was excavated by Basil Brown and the British Museum in 1939 at Sutton Hoo, near Woodbridge. The undisturbed grave goods were buried in a huge clinker-built ship some eighty feet long with provision for forty oarsmen. The ship and its contents were buried under a large mound of earth in a royal cemetery containing at least eighteen other mounds of various sizes. The astonishing treasure of 'royal regalia', weaponry, and objects of everyday use gives an important insight into Anglo-Saxon life at the beginning of the 7th Century. If it had not been for Sutton Hoo we would not be able to realise the incredible wealth, power, influence and connections of 7th Century kings in England. These burials parallel the 6th and 7th century boat-graves at Vendel and Valsgarde in Sweden. Possibly the Wuffings were kin to the Royal House of Upsala, the Scylfings.

|

|

The Raedwald Coins |

|

blank |

One of his grave goods was a purse containing Frankish gold coins, each one minted in a different place on the continent. For some time this has been interpreted as a gift from a continental king, but Dr Mark Blackburn is sure that such coins had been circulating in England for several decades. Therefore they could just as easily have been collected in this country.

|

|

The purse lid |

|

blank |

The purse lid illustrates the use of what we now call cloisonne work, where garnets appear to be sunk into a gold background. The garnets must have originated from the far east, with Sri Lanka as the most likely source. The buckle is said to be of Frankish origin, but some of the work is likely to have come from royal workshops at Rendlesham. Some pieces include the use of blue glass, which probably came from Kent, where the Roman Britons had learned its manufacture and use.

Clearly there were strong connections with Kent and the rest of 'England' and beyond that the European kingdoms from Gaul to Scandinavia. Political and economic commerce was sophisticated and highly developed by this time, with complex diplomatic activity connecting East Anglia to a much wider area.

Although the Wuffings stronghold was in south-east Suffolk, they probably had royal outposts or vills at places like Exning, Coney Weston and Bedericsworth in West Suffolk. Raedwald had also presided over a great trading outpost arising at Ipswich. For two centuries London and York had been the only major east coast trading ports. The presence of the Wuffings on the River Deben caused Sutton to be a busy port, but the higher reaches of the Orwell at Gipeswic were to become far more important. Gipeswic is today known as Ipswich and was to remain a busy port until the 20th century.

|

|

Helmet from Sutton Hoo

|

|

blank |

The great ceremonial war helmet shown here was placed in the grave by the head of the king. This helmet can be seen as a symbol of power and leadership, and has been interpreted as the anglo-saxon equivalent of a royal crown.

The king's pattern welded steel sword had a bejewelled scabbard with large buttons ornamented by a gold and garnet representation of a cross which must have been intended as Christian symbolism.

From the humble villages like West Stow, to the great wealth of the rulers, it is obvious that Anglo-Saxon society was highly stratified. In such a society there were obligations of protection, loyalty and service. The Wuffings drew their strength from the hundreds of little villages, like West Stow, which formed the backbone of their kingdom.

In turn, the people needed a strong king, for without the law and order that he could impose, they could not raise their crops and their families in safety.

|

|

West Norfolk hoard find 2021

|

|

blank |

For many years the Deben estuary and Rendlesham were seen as the only known seats of power at this time in East Anglia, based upon the Sutton Hoo finds. A coin hoard newly found in 2021 in West Norfolk must now question these assumptions.

The largest hoard of Anglo-Saxon gold coins to be found in England was declared treasure at an inquest held in Norwich in early November, 2021.

Four gold objects were discovered with 131 coins in a field in west Norfolk, most by an anonymous metal detectorist who notified the appropriate authorities.

Gareth Williams, curator of early medieval coins at the British Museum, said the "hugely important find", which dates to the same era as the Sutton Hoo ship burial near Woodbridge in Suffolk, is "the largest coin hoard of the period known to date".

The first coin was discovered in 1991, but it was not until 2014 that further coins, dating to about AD 610, were found.

Some were minted in the Byzantine empire, but most were from the Merovingian kingdom, which broadly corresponds to modern day France. Most of the coins are Frankish tremisses, and there are also nine gold solidi, a larger coin from the Byzantine empire worth three tremisses.

This includes coins struck from the same die in the same workshop as those found in a purse at Sutton Hoo. (The Sutton Hoo burial included a purse of 37 gold coins, three blank gold discs of the same size as the coins and two small gold ingots, as well as many other gold items.)

A stamped gold pendant, a gold bar and two other pieces of gold were found at the same time, suggesting the hoard should be seen as bullion, valued by weight rather than face value.

Tim Pestell, senior curator of archaeology at Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, said: “This internationally significant find reflects the wealth and continental connections enjoyed by the early Kingdom of East Anglia.

“Study of the hoard and its findspot has the potential to unlock our understanding of early trade and exchange systems and the importance of west Norfolk to East Anglia’s ruling kings in the seventh century.”

|

|

626

|

Around 625 we believe that Raedwald was succeeded by King Earpwald, one of Raedwald's sons, but Earpwold could not inherit his father's position as high king, or Bretwalda, over the other English kings. It seems that Edwin of Northumbria was now accepted as Bretwalda, or High King of England. Edwin or Aedwine had actually been placed on the throne of Northumbria by Raedwald after the battle on the River Idle in 616.

Aedwine had allowed Paulinus to set up a church in York, and to spread Christianity in Northumbria. Paulinus had gone to York with Aethelburh, the Christian sister of Eadbald of Kent, when she married Aedwine in 625. However, Aedwine was not yet ready to accept baptism and make the new religion an official part of his own rulership.

Ipswich was now coming into some prominence on its present site and was notable for the distinctive Ipswich-ware pottery thought to have been produced here from c.620 to c.850, after which Thetford-ware came to dominate. (However, the start date of 620 has now been called into question, and suggested that Ipswich Ware did not come into production until 50 years later. At present this must be taken as a consideration.)

Penda became King of Mercia and ruled until 655. Penda was a committed pagan and would use his opposition to Christianity to forge alliances against the new Christian kingdoms. As the power of Penda would grow, historians consider that East Anglia would decline in power.

|

|

627

|

King Aedwine of Northumbria finally decided to accept Christian baptism, and destroy the pagan temples in his kingdom. On 12th April 627 he was baptised at York by Paulinus, along with many of his nobles, family and friends. Bede was very impressed by Aedwine's kingship and Christian values, whereas he had regarded Raedwald as ignoble because of his twin altars. Raedwald had apparently failed to make his own sons into Christians, so now it was Edwin who was said to have persuaded Earpwald of East Anglia to convert to Christianity. Earpwald would have seen this as part of his alliance with the Bretwalda.

Although Raedwald had been a baptised Christian, he does not seem to have tried to convert others to his faith, an attribute which Bede gives to Aedwine, and the new religion now gained further strength in East Anglia. However, it seems that there were still powerful adherents to the old ways who had mortal objections to a Christian rule in East Anglia.

Our main source for the period, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, tells us that the reign of Rædwald’s son Eorpwald ended in assassination and backsliding. He says in Book II, chapter 15:

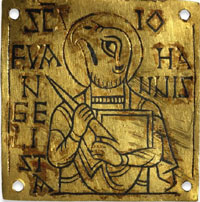

"Not long after Eorpwald's acceptance of Christianity, he was killed by a pagan named Ricbert, and for three years the province relapsed into heathendom."