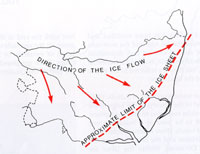

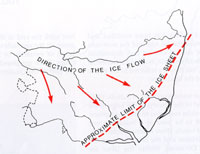

The Anglian Glaciation |

The Chronicle of

our local watermills

|

100 AD

|

By the end of the 1st century there were six small "Roman" towns in Suffolk. Their inhabitants would have been largely the native inhabitants, but with officials answerable to the Roman Empire, and a smattering of peoples from across the countries of the Empire. Administration of the area was probably from either Venta Icenorum, (Caister by Norwich), or Colchester.

Most, if not all, of these towns would have been existing settlements of the existing celtic tribes.

The six towns, from west to east, were:

- Icklingham

- Long Melford

- Pakenham

- Coddenham

- Scole

- Hacheston

|

|

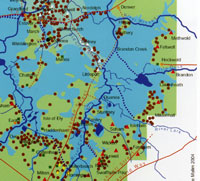

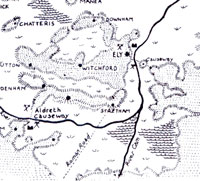

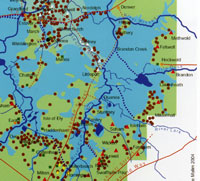

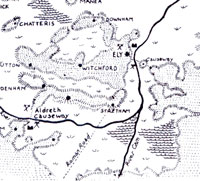

The Fens in Roman times

The Fens in Roman times

|

|

140 AD

|

During the time of the Emperors Hadrian and Antony, from 120 to 140, much of the infrastructure of the Roman Fens was put in place. On the River Lark a canal was built from Isleham to Prickwillow. This was probably to ship out clunch as a building material from Clunch Pits at Isleham. No doubt it also served to improve local drainage as well.

The map shows an intensive cluster of settlements along the fenland edge, indicating a prosperity and activity which has not been fully recognised in the past. The Fenland edge was a hive of activity in Roman times, with trading boats coming and going, industrial workshops and settlements supported by the rich natural resources of fish and game available from the waters. Summer grazing was widespread on the water meadows, and thatching reeds were widely available.

Hockwold in particular became an important port in the area.

|

|

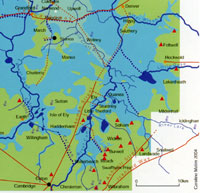

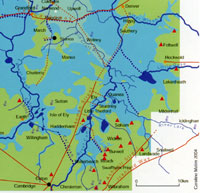

Fens in late Roman times

Fens in late Roman times

|

|

350 AD

|

By late Roman times the settlements which were successful had expanded. In West Suffolk the development of Camborito at Icklingham probably indicates a west facing town, with its lines of communication concentrated on the waterways of the fens. The fenland edge continued to be a centre of Roman prosperity in Suffolk.

|

|

410

|

In the year 410, the cities of Britain were officially ordered by the Emperor Honorius to take responsibility for their own defences. In the same year the Goths took Rome and an important result of the collapse of central Roman rule was that no further coinage was imported into Britain. In addition, no new coins seem to have been minted in England from 411 to about 630.

It was the beginning of the end - administrators, specialists and the military could not be supported by money. There was no money to pay for the infrastructure of roads and canals to be maintained. The drainage works in the Fens were largely abandoned over the next few years.

From 410 to 442, Britain was independent from Rome, and this was the last age of Roman Britain before the Saxons were to effectively take over.

|

|

430

|

After a short time the number of Saxons allowed to settle increased and new areas were penetrated. Very early remains have been found at Caistor by Norwich, Luton and Abingdon. These were strategic settlements, to protect the Cotswold heartlands, and Norfolk was particularly well settled. Because the north still had the army, there was less need for reinforcements to be sent there. Forces were placed to protect the North road, the Thames estuary and the major intersections of the Icknield Way. These inland posts were really a defence line of last resort.

One of these posts might have been at West Stow, sitting on the River Lark crossing of the Icknield Way.

A sprawling half mile long Romano-British settlement possibly known as Camborito had been long established at adjacent Icklingham, and a Roman villa has also been identified there. Finds have been made here over many years and four lead water tanks have now been discovered in Icklingham bearing Christian symbols. In 1974 an apparently Christian cemetery was found with a possible Christian chapel.

Around this time it appears that the Anglo-Saxon village Stowa was first established just the other side of the Icknield Way from Camborito. Exactly how they interacted and how relations changed over the next 50 years we do not know. The Romano-British were Christian at this time and the Anglo-Saxons were pagans.

|

|

Anglo Saxon Village |

|

460

|

The Lark, Blackbourne and Ouse valleys of West Suffolk had been settled by these mixed Angles, Saxons and Friesians by this time, including at West Stow.

The village of Stowa, as we call it today, was located on a small hillock by the River Lark, on very light sandy soil. The Icknield Way crossed the River Lark at a ford a few yards away, running roughly north and southwards. An old Roman road ran east and westwards a few yards north of the village. This road led to the old Romano British village of Camborito, just a few hundred yards to the west. The village cemetery was just across the Roman road.

The Central Suffolk clay soils do not seem to have attracted the Anglo-Saxons. They preferred the river valleys, and more easily worked soils. Other settlements have been excavated at Honington and Grimstone End in Pakenham. We do not know exactly when Bury l was first settled by Anglo-Saxons, but we have a better idea of where it took place. In modern Bury we have evidence of several Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, so there were probably at least four small villages within the area of today's town. One was probably where the Abbey's ruins remain today, one near Barons Road, one at Westgarth Gardens and one near Northumberland Avenue.

It seems that the settlers in West Suffolk were based along the river valleys which flowed into the Fens, and that they looked to trade in that direction rather than to the east. It seems likely that West suffolk was thus settled from the direction of the Wash, through the Fens, while East Suffolk was settled up the river valleys like the Gipping, Stour and Waveney, which all flowed eastwards towards the North Sea.

|

|

Gold pendant from Undley |

|

500

|

In the Fens the Roman drainage system built around Car Dyke had failed as there was no administration to maintain it against the rising sea levels. Areas of Fen now flooded, leaving only Ely and a few other islands above the water level. Along with this problem came a rise in sea levels through the 4th and 5th centuries, so that by this time East Anglia was a virtual isthmus, cut off from the area of Mercia to the West by the great marshy fenland.

|

|

Anglo Saxon horse burial |

|

550

|

Around 550 a Saxon nobleman was buried with his horse at Eriswell. The site was discovered in 1997 under a baseball pitch scheduled for redevelopment on the USAF base at RAF Lakenheath. Some 200 graves were located on the site, spanning a period of 150 years. This is now a completely different form of burial than the earlier cremations exemplified at West Stow.

Over the next 5 years more graves were discovered. Eriswell had three cemeteries with 446 graves finally identified. This is a major find for East Anglia and covers the late 5th to early 7th centuries. There were other horse burials found, but the first one in 1997 aroused the most excitement.

|

|

Defensive dykes on Icknield Way |

|

c.575

|

The Devil's Dyke at Newmarket, and the Fleam Dyke, a few miles further to its south west have long been believed by some historians to date from around this time to defend from attack from the west. Recent detailed work has confirmed that these earthworks date from the 5th to the 7th centuries. They are also aligned to face an attack from the south west.

|

|

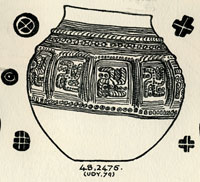

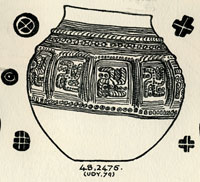

Lackford Cremation Urn & potmarks

|

|

585

|

In 1947 T C Lethbridge excavated a pagan Saxon cemetery at Mill Heath, Lackford. The site is above the 50 foot contour on a peninsula of land between the south bank of the River Lark and a the Cavenham Mill stream. He found between 400 and 500 cremation urns, a concentration which is unusual for the Lark Valley, where earth burials, or inhumations, are more prevalent. There were swastikas present upon a number of cremation urns, and the Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Lackford has yielded some of the most exquisite designs of this image.

|

|

635

|

In his later years Sigeberht was reported by Bede, to have handed over all his authority in East Anglia to King Egric, probably the man known to other historians as Aethelric. Aethelric had already been ruling over part of the territory of East Anglia in a joint arrangement with Sigeberht.

Sigeberht himself thus appears to have been the first English king to abdicate. His reason was in order to become a monk.

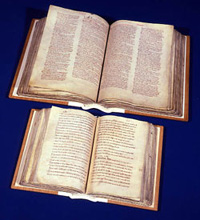

Around 635, Sigeberht had founded a monastery at Bedericsworth, today called Bury St Edmunds. Bede states that he built the monastery for his own use. It was one of the earliest schools of English literacy, but it was not the type of structure whose ruins we see today, but was probably made of wood. The site may have been very close to the later abbey site at Bury. Bede recorded that Sigeberht now retired to live in his monastery. A marginal note made in the 12th century book, the Liber Eliensis, is the only evidence we have which identifies its location as Bury. He entrusted his earthly kingdom to his kinsman, Egric, (or Aethelric), who had already governed part of the kingdom , and "devoted his energies to winning an everlasting Kingdom".

Both Ipswich ware and Thetford ware have been excavated from the site of the Bury monastery, indicating an occupation here between the 7th and 9th centuries.

Why would Sigeberht have chosen this location at Bedericesworth? Did the Wuffing royal family perhaps own, or have rights over, land in the area? Did a relative already live on the site? Or was it a site of wilderness and marsh, peopled with demons and spirits, sorely in need of a holy presence?

The site was bounded by the River Linnet to the South, the River Lark to the east and the marshes of Tay Fen to the north. In reality it was probably surrounded by marshy pools and waterways, and quite isolated. As far as we know the Romans had failed to be attracted to Bury, and by this time there were a few anglo-saxon villages occupying the river banks in the area nowadays covered by the town. It was a good place to seek isolation, far from the royal court at Rendlesham, but safely inside the Wuffing kingdom.

With an abdicated king in residence, this would have been the start of the settlement as a villa regia or royal town. Over the years it was possibly able to acquire such rights as holding a market, but more importantly, charging market tolls.

Eventually the rivers may well have been used to transport some goods to and from the small market.

|

|

650

|

The title of middle Saxon Period is assigned to the period from c.650 to c.850, when Christianity was being adopted by the formerly pagan Saxons. Other names for this time are Early Medieval or Christian-Saxon.

The West Stow Anglo Saxon Village site was deserted at about this time, but possibly moved to the location of the current West Stow village, around a Christian church and cemetery. There is evidence that other pagan Saxon settlements in Suffolk were abandoned at around this time, possibly to make a clean start on a new Christian site.

During the Middle Saxon period the Fens and the clay soils were settled once again so that by the 9th Century most of our villages had been founded. However, we need to remember that the sites of named villages may have moved over time since then.

|

|

700

|

In England waterwheels were used from the Roman times onward. The Domesday survey records that of the 9,250 manors mentioned, 3,463 had 5,624 mills. During the Middle Ages, watermills were used for grain-grinding, drainage and fulling. We do not know when the first watermill was established in our area. However, the first known mill in Herefordshire was at Wellington dated by dendrochronology to 696 AD. So watermills were potentially known about at this date, in this country.

|

|

865

|

Modern historians refer to the 200 year period after 865 as The Late Anglo-Saxon time. This is because the year 865 heralded disaster for Anglo-Saxon England. It was the year of full scale invasion by the Great Army of the Danes.

|

|

869

|

From York the Great Army of the Danes marched back into East Anglia, but this time they attacked Thetford. Thetford stood on the Icknield Way, at an important crossing point of the Rivers Little Ouse and Thet. The town could be reached not only by the army on horseback but, most importantly, their ships could reach Thetford by sailing into the Wash and then following the rivers through the Fens.

" The Danish took the victory and killed the king and conquered all that land, and did for all the monasteries to which they came. At the same time they came to Medeshamstede (Peterborough) : burned and demolished, killed abbot and monks, and all that they found there, brought it about so that what was earlier very rich was as it were nothing."

The Danes also attacked Crowland Abbey in the Fens, and burned it down. Other monasteries assumed to have been destroyed around this time include Beodericsworth at Bury St Edmunds, Ely and Soham. Iken, Brandon and Burrow Hill were deserted, and may well have already been destroyed in the earliest attacks. Dommoc disappeared so completely that we are still debating its exact location.

The town of Thetford seems to have been attractive to these invaders as a base in East Anglia. They could bring their longboats up the Wash and follow rivers into the Little Ouse, and on to Thetford. Thetford also had ancient iron age earthworks which could be pressed into service as a camp and horse stockade. Thetford was certainly revived in importance from these beginnings as a Danish winter stronghold. For the next fifty years, East Anglia was under viking control.

|

|

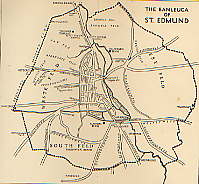

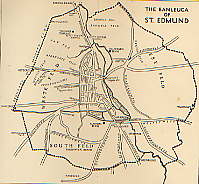

Banleuca Boundaries by C R Hart

|

|

945

|

According to an Anglo-Saxon Charter, in 945 King Edmund gave up his royal rights to taxes and all feudal dues and fees in the area of Bury St Edmunds for about one mile around St Edmund's shrine.

|

|

997

|

From 997 to 1014 viking raids occurred every year.

By this time Norwich was catching up with Thetford as the main city of the Norfolk area. It had better access to the sea than Thetford and could handle more trade more cheaply because of this advantage.

|

|

1014

|

On 28th September, 1014, a natural disaster occurred when "that great sea flood came widely throughout this country, and ran further inland than it ever did before, and drowned many settlements, and a countless number of human beings." Low lying settlements in the Fens and the Broads areas were especially vulnerable, just as they still are today.

|

|

1016

|

After the Battle of Assendun, King Cnut followed King Edmund into Gloucestershire. Ealdorman Eadric and the councillors now tried to broker a peace between the two kings, and the kings agreed to meet at Ola's Island in the River Severn. It was agreed that King Edmund kept Wessex and the land south of the Thames, and the rest went to King Cnut. The Danish raiding army was paid off, and their ships went to London.

King Edmund Ironside died on 30th November, St Andrews Day, within a month of the Battle of Ashingdon, and so Cnut received all the kingdom. He was the first Danish King of all England, and was 23 years old. He was the famous King Canute, who was so upset by the constant praise of his court, that he is said to have demonstrated that he could not hold back the tides.

King Cnut or Canute, was descended from a long line of Danes who had caused great misery in England. One of his ancestors was Ivar the Boneless, who had killed St Edmund. He was the son of King Sweyn Forkbeard who had died suddenly (so it was said), after threatening to sack St Edmund's town. St Edmund must have hovered in the background of Cnut's mind as a saint not to be trifled with.

East Anglia, and indeed all England, was now once more under Danish rule and was to remain part of a large Scandinavian empire until 1042.

|

|

1014

|

Queen Emma now held the Eight and a Half hundreds of West Suffolk, and set herself up in the 12 carucate Manor of Mildenhall, a large and prosperous estate. From here she controlled the patronage of St Edmund, and seems to have also been a patron of the whole of East Anglia. In practice she had all the privileges of the Earldom, as well as the specific control of the Eight and a Half Hundreds.

|

|

1042

|

Danish rule finally ended when Harthacnut collapsed and died "as he stood at his drink, and he suddenly fell to earth with an awful convulsion.... he spoke no word afterwards... and he passed away on the 8th June." He was succeeded by King Edward the Confessor.

|

|

1044

|

King Edward the Confessor now handed all of former Queen Emma's West Suffolk income over to the monastery at Bury under Abbot Leofstan, who was only the second Benedictine abbot there. In modern English it includes the following clauses:

"Edward the King greets Bishop Grymketal and Aelfwine, and Aelfric and all my thanes in Suffolk friend-like; and I make known to you that I wish that land at Mildenhall and the nine less a half hundreds in sanctuary to Thinghoo belong unto St Edmund with soke and sack as full and as forth as it stood in my mother's hand...."

|

|

1066

|

King Edward the Confessor died on 5th January 1066, and the Chronicles say that he committed the kingdom to Harold Godwinson. Within a year the Normans had invaded England. On 25th December 1066, William the Conqueror was crowned King of England and Anglo-Saxon England was no more. The Norman Conquest had taken place, and would be followed by a great takeover of Saxon property.

|

|

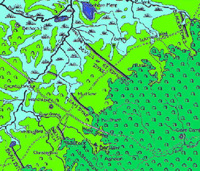

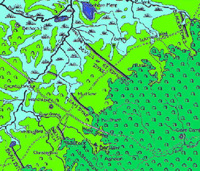

The Fens in 1071

The Fens in 1071 |

|

1071

|

The revolt of Hereward the Wake in 1070 and 1071 has been said to be a minor affair by contrast to the northern revolts, but has attracted more attention from some writers.

At this time the water table in the Fens was probably 30 feet higher than it is today, with swamp and marshy, reedy waterways the norm. There was no agriculture of the type seen today. Instead it was a vast fishery, with some reed cutting where possible, and grazing in the summer months. Eels were widely trapped, even giving Ely its name. Ely was an island with four main landing places or hythes. Even at Bury the River Lark was deeper than it is now, with the town almost surrounded by the waters of the Lark, Linnet and Tay Fen, and their flood meadows. The River Lark then joined the Ely Ouse at Prickwillow.

The Isle of Ely itself was a haven by comparison to the surrounding Fen. The isle covered seven miles by four miles and enjoyed a high standard of farming on its drier rich soil. The Abbey itself was a rich endowment, and the town of Ely was substantial.

The revolt was soon crushed, and the losing Saxons had more of their lands confiscated.

Of the 10,000 men who crossed the Channel with King William, some 2,000 were rewarded with grants of land. Within a short time, ten of King William's relatives owned 30 per cent of English land. Prominent among them in Norfolk were the Bigod and Warenne families. The Bigods also had great estates in Suffolk.

|

|

Click for more on Domesday

|

|

1086

|

At St Edmund's Bury the Domesday book recorded 500 dwellings, and many of the inhabitants depended on the monastery for a living. Some 75 bakers, ale brewers, tailors, washerwomen, shoe and robe makers, cooks, porter and purveyors "daily wait upon the Saint, the Abbot, and the Brethren." The Domesday Book recorded 30 priests, deacons and clergymen in Bury together with 28 nuns and poor people who "daily utter prayers for the King and all Christian people". Bury's population might have grown to 2,250 by 1086. The town was now valued at £20, or twice its value in 1066.

Many of our local villages were recorded as having a mill, which at this time always meant a watermill. A wintermill was a mill where it could only be operated in winter because of the shortage of water during the summer months.

|

|

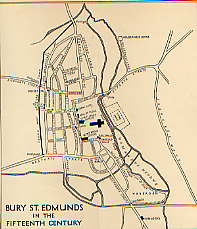

Bury by 1150

Bury by 1150 |

|

1150

|

By this time,

according to the Gesta Sacristarum, Harvey the Sacrist also built the town walls of Bury to replace the ditch from the West Gate to the North Gate.

Chequer Square was at this time called Paddock Pool and its swampy nature was a problem for the medieval builders.

|

|

Battle of Fornham

|

|

1173

|

Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, now raised a force of French and Flemish mercenaries. On September 29th, they landed at Walton near Felixstowe and marched inland.

They joined up with Hugh Bigod, and attacked Haughley castle and badly damaged it, killing many of its defenders.

The Earl of Leicester was persuaded to head for Leicester to capture his home town. So they first headed west, through Suffolk and towards Bury St Edmunds. Beaumont knew that Bury supported the old King, and so he aimed to skirt north of the town.

Meanwhile Hugh Bohun and Richard de Lacey, the army commanders of Henry II in the north had agreed a truce with King William of Scotland, regrouped and were marching south to meet the threat. Local Suffolk people joined them as they neared Bury, in particular those whose homes and families had been ravaged by the Fleming militias.

So in the in autumn of 1173 the opposing armies met at Fornham St Genevieve on the River Lark, some four miles north west of the centre of Bury. The Flemish army was caught as it tried to cross the marshes down to the River Lark looking for a suitable fording spot. Fighting seems to have taken place from the Babwell hamlet, by today's Tollgate Inn, along the valley to Fornham. The rebels' strongest position was somewhere near Fornham St Martin Church.

The Earl of Leicester and his wife, the Countess Petronilla, were captured, but Earl Hugh Bigod escaped to Bungay. The Countess was said to have thrown her ring and other jewels, into the River as a gesture of defiance. The Earl and his Countess were later taken to Normandy as prisoners.

Bones and a few lost weapons have been found in the area of the battle, including the Fornham Sword, which is now in Moyse's Hall Museum, on loan from John Macrae, the landowner. This was found when a muddy ditch was being cleaned out near the water mill at Fornham St Martin around 1876.

|

|

1184

|

In about 1184 Samson founded a new hospital called St Saviour's at Babwell. The site is on the Fornham Road, outside the old North Gate. Today it is adjacent to the railway bridge, next to Tesco's store.

St Saviour's backed on to the River Lark, providing water and fish.

|

|

1186

|

Around this time the windmill was introduced to this country. Up to this time all mills were either animal powered or were water mills. A mill built on the Haberden in 1191 must have been one of the first in the country.

|

|

1191

|

Around 1191 Herbert the Dean erected a windmill at the Haberden, off Southgate Street, in Bury St Edmunds. The Guinness Book of Records for 1964 claimed that this was the first recorded Post Mill in England. The post mill was built around a central column or post which allowed the mill to be turned to face into the wind whenever the wind direction changed. If this was the country's first post mill, it did not last very long. To protect his own income from the milling fees, which he charged at his own watermill, the Abbot forced him to take it down. Windmills were the latest technology at this time. Hitherto the watermill had reigned supreme, and it seems that the Abbot had a Water Mill based on the River Lark, within the Abbey precincts. Water power itself had replaced the animal power long used in earlier times to grind corn.

|

|

1200

|

Through the 1190's and early 1200's, the new technology of the time in the wool trade was the invention of the water driven Fulling Machine. This was to turn England from being an exporter of raw wool to Flanders and the Low Countries, into a manufacturer of textiles on an industrial scale. This needed fast flowing water to drive the machines and new centres would grow up in the Cotswolds, and also in and around the Stour Valley, not far from Bury, over the next hundred years.

|

|

1265

|

By 1265 the Abbey finally gave the Franciscans land for a permanent home at Babwell just outside the Banleuca where today's Priory Hotel stands. With land given reluctantly by the Abbey at Bury, and financial help from the Earl of Gloucester, Gilbert de Clare, the Franciscan Friars finally founded their Friary at Babwell. The name Babwell no longer survives, but the Priory Hotel stands within the walls of the old Friary precincts at the junction of Tollgate Lane and the Mildenhall Road. Only remnants of the walls remain visible today.

The Friary backed on to the River Lark, and the Friars would soon establish their own watermill. There have been remains of a mill found behind the Tollgate Inn, possibly associated with the Friary.

|

|

1273

|

In March there was so much rain that there were floods worse than any since 1258. Water rose 5 feet above the bridge at Cambridge, and the damage at Norwich was said to be worse than the ravages of either the disinherited or the king's men last year.

|

|

1277

|

A cloudburst in October caused many men and livestock to be drowned in the floods. The storms were worst in Essex and Cambridgeshire and around Bury itself.

|

|

1281

|

In 1281, the manor of Haberdon, or Haberden, was granted to the Sacrist of the abbey by Henry, son of Nicholas of St Edmund. This would add to the sacrist's income, and included a mill, and at least 51 acres. As the abbey gained more and more of the local pasture land, any common rights hitherto exercised by local people were gradually extinguished by the new owner.

|

|

1282

|

A record in William of Hoo's Letterbook concerns a lease of a toft, or shop, in Icklingham, together with a Fulling Mill. This would have been located on the River Lark, using a combination of water and Fuller's Earth to clean the grease from woollen fleeces. William the Sacrist would receive his annual rent from the lessees, Robert the Fuller of Icklingham and his wife Cecily.

|

|

1290

|

The cellarer had dammed up the Tayfen brook, and flooded some lands used by towns people. The leading townsmen were united against this act, and called a meeting in the Guild Hall. They then set out to destroy the dam. In October, a commission was set up to enquire into their actions, but this only made matters worse. This rumbled on into more violence in 1292.

|

|

1300

|

During the 14th Century, from 1300 to 1400 Bury St Edmunds had a flourishing fishing industry. Amazingly to us today, the Rivers Linnet and Lark, with the waters at Tay Fen and Babwell Fen, supported large fish populations. These provided employment for fishermen and food for the town and abbey, as well as a means of transport, source of drinking water and a means of waste disposal. Gradually the pressure of the fulling mills and their waste products, and a rise in population pressure would cause a decline in fish production.

In the century 1300 to 1400 it seems that the climate was much warmer than today. On a global scale the glaciers were melting, resulting in a rise of sea level, to about half a metre higher than it was by about 1987. Coastal erosion accelerated at an alarming rate, destroying some coastal communities, and severely damaging others. In Suffolk, the prosperous port of Dunwich would become the best known casualty, but on the Humber, the port of Ravenspur would suffer the same fate. It is likely that inland the river levels would also tend to rise, as sea level rose.

|

|

1342

|

The rise in sea levels since about 1300 had severely affected the coastal communities by this time. In particular, by 1342, Dunwich had lost 400 houses, together with the churches of St Leonard's and St Martin's. A century earlier it had been at the height of its power and prosperity as one of the largest ports in eastern England, perhaps about half the size of London.

|

|

1379

|

Although Bury and Thetford were inland towns, they both acted as ports, particularly Thetford as it had a bigger river. In 1379 the royal council ordered the two towns to build a ship to be incorporated into the royal navy. This was a feudal duty of the town bailiffs in Bury.

|

|

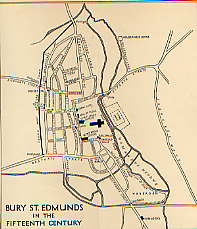

Lobel's map of Bury |

|

1433

|

This map of Bury by M D Lobel shows the River Lark, the Linnet and the Tayfen Brook enclosing the medieval town.

|

|

1440

|

From about 1440, the rearing of sheep became more profitable around Bury than the rearing of cattle. Cattle had been kept for years in and around the town, supporting the leather industry as well as for food. The wool from sheep was now becoming much more valuable for weaving into cloth. This led to an extension to the number of sheep folds around the area.

With the increased cloth production around Bury, it would appear that the fulling and dying of cloth were polluting the waterways of the town. At any rate the number of people in the town calling themselves fishers seems to have fallen dramatically at this time. The river and fen fishing industry became moribund.

|

|

The Banleuca by 1450

|

|

1450

|

From 1450 to 1530 the cloth industry would reach a peak of prosperity.

This was particularly marked in the broad cloth area of Suffolk, between Clare, Bury St Edmunds and East Bergholt. Bury St Edmunds was the principal market outlet for the woollen cloth of the Stour Valley, as well as being a major producer in its own right. Merchants came to Bury's wool markets from London, Norwich, Kings Lynn, Great Yarmouth, the Low Countries, Germany and Italy. They were seeking the cloth from the finest fleeces in Western Europe.

As well as the better known textile villages, places within ten miles of Bury like Woolpit, Rattlesden, Thorpe Morieux, Boxstead, Icklingham, Stanstead and Mildenhall were centres of the weaving trade, sending cloth to Bury. Today, Lavenham and Long Melford are well remembered as wool towns, but it is important to understand how widespread the trade was in this area.

Some clothiers would become extremely rich on this trade, particularly in Babergh and Cosford hundreds. Lavenham became the greatest centre for cloth with the most clothiers. Hadleigh, Lavenham and Bury St Edmunds had the greatest output of cloth followed by Ipswich, Nayland, Waldingfield, Long Melford and Sudbury.

By 1450 it is reckoned that about half of Bury's export trade was through Kings Lynn, by way of the Rivers Lark and then along the Great Ouse.

|

|

1455

|

By the mid 1400's the Breckland area to the north-west of Bury, began to change in character. The light soils had been ideal farmland from the earliest years because of its good drainage and easy ploughing and cultivating. By this time the soil was exhausted, and tillage gave way to the keeping of sheep and rabbits. Climate change may also have resulted in lower rainfall resulting in crop failures. Sheep farming was also becoming more profitable, but the resulting over grazing would lead to the great erosion problems of later centuries.

|

|

Moulton Packhorse bridge

|

|

1477

|

Moulton, a village four miles east of Newmarket, is known for its 15th century Pack Horse Bridge, now maintained by English Heritage. The bridge is on the old Cambridge to Bury St Edmunds packhorse route and was one of the main arteries for Bury's wool trade. Its low parapet walls enabled the packs to swing clear and avoided the need for a wider, more expensive structure. However, it was probably not restricted to packhorses, as it is wide enough to allow the passage of small carts. It can still be used to cross the River Kennett, but nowadays the river is usually completely dried up. There was probably another packhorse route from Clare to Newmarket joining up with this route.

The River Kennett drains towards the north west, flowing into the Lee Brook at Freckenham, and thence into the River Lark between Jude's Ferry and Isleham.

|

|

1521

|

A deed found by the Ingham Local History Society for their book on the Culford Estate, dates to 1521, and refers to a parcel of land between Hengrave Mill and "Chimneymylle". Also found was a lease of 1661, when it was called 'Chimney Mill alias Hurdles Mill.' Clearly the Victorian chimney which now characterises Chimney Mill, had no place in 1521. The source of the name is more likely to have come from the shape of the long thin plot of land on which it stood.

|

|

1534

|

In about 1530 John Leland, the Keeper of the King's Libraries, toured around East Anglia. It is said that in 1534 John Leland visited Bury. Most of his comments on provincial towns were far from flattering, but in the case of Bury he wrote that:

"Why need I in this place extol Bury at greater length? This only will I add, that the sun does not shine on a town more prettily situated, so delicately does it hang on a gentle slope, with a little stream flowing on its east side, nor on an abbey more famous....

The streamlet, which I just now mentioned, flows through the midst of the abbey precinct, gaining access thereto by a double bridge vaulted over it."

The "little stream" does not seem to have been named the Lark until about the seventeenth century. In 1699 there was enacted "an Act for making the River Larke, alias Burn, Navigable". In 1534 it was small and shallow and could not take deep draught vessels, so only flat bottomed barges could reach the town, usually poled by men or pulled by oxen or mules.

|

|

1536

|

The Dissolution of the Monasteries really began when the Act of Suppression authorised the closure of monasteries with an annual income of less than 300 marks (about £200). This Act began to be enforced in 1536. It covered 300 houses but about 75 were exempted upon payment of a fine.

In Bury this order did not cover the great Benedictine Abbey, but it did cause the Babwell Friary of the Franciscan Order to be shut down. Its site on the Lark, together with its watermill, became Crown property. The property of the Babwell Friary was then sold to Anthony Harveye, a gentleman.

|

|

1539

|

In September 1538 the Kings Commissioners had arrived in Bury to confiscate its wealth. The property of the Abbey of St Edmund was not formally surrendered to the Crown until 4th November 1539 but much of the wealth had already been confiscated in the previous year.

|

|

1540

|

When Sir John Crofts purchased the manor of West Stow, following the Dissolution of the monastic lands of St Edmunds, the deeds recorded a water mill and a fulling mill. One of these mills was Chimney Mill, a name recorded as far back as 1521.

|

|

1542

|

There were a series of droughts in the 1540's, and the resulting food shortages pushed prices up further. In 1542 the Thames dried up to a trickle, followed by widespread crop failures and many small farmers were forced out of business.

|

|

1550

|

The climate has not always been just as we experience it today. We all know about the Ice Age which was thousands of years in the past, but from about 1550 to around 1850 there was a cooler period, sometimes called the Little Ice Age. Prior to this time there had been a warmer period, called the Medieval Warm Period, from about 800 to about 1300.

After the mid 1500's there were colder winters than we are used to today, with great hardship for man and beast.

|

|

1560

|

On 14th February, 1560, Queen Elizabeth in consideration of £412 19s 4d. paid by John Eyer, Esq., granted him (amongst other things) "All that the site, circuit and precinct of the late dissolved Monastery of Bury, otherwise called "Bury St Edmunds" amongst the specified lands and buildings being the Dorter Court, the Garners, the Abbot's Stables, the Gate House, the Great Court, the Pallaies Garden, the Lecture Yard, Bradfield Hall, the Pond Yard and the Vine."

The abbey's fishponds were therefore still visible at this time, but it is unclear if they still held fish.

|

|

1635

|

The attractive profits to be made by reducing the cost of transporting goods across country continued to make river improvement an attractive idea. In 1635 the entrepreneur Henry Lambe managed to obtain an Order in Council which gave him permission to carry out whatever work was needed to make the river navigable from Mildenhall to Bury St Edmunds.

However, all along the river there were watermills which depended upon a free flow of water for there existence. In some cases they were situated on mill streams flowing into the river, but in some cases they sat upon the river itself. Although these could all be avoided by digging new cuts around the mills, some millers feared the worst.

After proceeding only one mile, the landowners Sir Roger North and Thomas Steward, lodged objections, as a miller claimed that the contractors had damaged his mill. They managed to get the work stopped.

|

|

1636

|

Apparently Lambe managed to get permission to restart the works, but only if he paid treble the cost of any damage to mills, and agreed to pay an exorbitant price to buy any necessary land for towpaths and cuts.

|

|

1700

|

By 1700 Henry Ashley the younger became the licensed "undertaker" for the River Lark, as described in the Act of 1699. He had already worked on building the Great Ouse navigation with his father. It took until 1715 for the works to be completed.

Canal technology at this date did not include the use of "pound locks", as we know them today. Instead they used staunches and sluices. A staunche, or stanche, was like a single lock gate, controlling the level in a stretch of river. Staunches controlled a weir which was made into a slope so that boats could pass from one level to another. Boats either had to navigate with, or against, the rush of water or to wait for the whole of pounds on either side of the weir to become equal. This system is also called a Navigation Weir or Flash Lock. A sluice is a confined water channel that is controlled at its head and foot by gates, and to all intents and purposes appears to have been very similar to a modern lock.

Obviously the proposed works were a threat to existing users of the river, in particular, the water millers. One way that Ashley dealt with this issue was to take the problem over to himself. In October of 1700 he leased the Chimney Mills from Lord Cadogan for 25 years. In fact, this mill would remain in the hands of the River Lark Commissioners for the next one hundred years. The miller at the time seems to have been Samuel King, and he stayed on until his death. His widow finally gave up the mill in 1722.

In addition, the Act empowered any miller on the river to convey his own building materials free of toll on the new River, provided that the materials were for the repair or improvement of his own mill, the mill banks, dams, stanks, or gates pertaining to his milling operations.

|

|

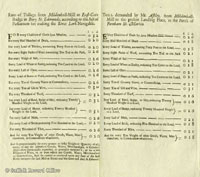

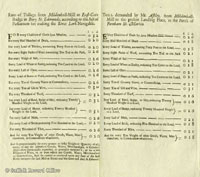

Ashley's tolls for using River Lark

Ashley's tolls for using River Lark

|

|

1716

|

The Lark navigation was now open for business from Mildenhall to Bury St Edmunds under the Act of Parliament passed in 1699/1700. By 1700 the River Lark was no longer navigable any further than Mildenhall from the sea, and so Henry Ashley obtained the Act to allow navigation as far as Eastgate Street. The Corporation of Bury were apparently afraid of him setting up a wharfage monopoly, and opposed the plan. All Ashley could do was build his canal as far as Fornham, outside the Borough boundary.

By 1716 Ashley had acquired the mill at Icklingham, thus removing one other possible source of dispute over water rights.

|

|

1722

|

Some local interests continued to plague Ashley. In 1722 there was a dispute with Mr Ralph at Mildenhall Mill. He seems to have had a string of grievances, but he was now threatening to pull up the Mildenhall Lower Staunch. He felt that he was not getting enough water to drive his mill. Ashley had avoided such disputes at Icklingham by buying the mill himself.

Ashley had now apparently accepted that he had to make his permanent terminus at Fornham, just outside the boundary of the Borough of Bury St Edmunds. He bought the Priory Estate from Bridget Short, consisting of 8 acres including Babwell Fen meadows and Bell Meadow.

|

|

1735

|

In August 1735 John Kirby published his book called "The Suffolk Traveller". Of Bury, Kirby wrote in glowing terms, and also noted that:

"Bury St Edmunds is situate on the west side of the River Lark, which is at present navigable from Lynn to Fornham, a mile north of the town."

Goods were not just delivered to Bury St Edmunds, but were dropped off at villages along the river as required. The miller at Icklingham was being paid 40/- a year in 1735 to look after the Temple Staunch, and £5 a year for collecting the tolls payable on deliveries to Icklingham.

|

|

1800

|

During the late 18th century the nature of milling changed. Up to this time a mill would serve its local area and small farmers brought their corn to the mill to be ground. The miller would be paid by keeping a proportion of the flour that he produced from each milling. In the late 1700s the miller became pro-active in the process. He began to buy corn at the new Corn Exchanges for himself. He hoped to buy at cheap prices, and store some of his purchases until flour became scarce. Then he would mill it and sell the flour on the open market and make his profit that way.

Mills also changed as the miller needed to store the corn he had bought. Thus mills grew another storey, and corn hoists were extended to lift corn up to the top floor for storage. Hopefully this was the driest part of a water mill, and the hardest for vermin to penetrate.

|

|

1802

|

In November 1802 the poor state of the Lark Navigation, combined with a drought, left the coal yards of Bury St Edmunds empty. There was not enough water to float the barges. Susanna Cullum, the proprietor of the river, was perhaps too old to carry out the necessary improvements.

Records tell us that in 1802, goods were being landed at the villages of Icklingham, Lackford, Flempton, and Chimney Mills, as well as at the Fornham Wharf. Coal was not delivered to most villages as it was too expensive. Coal was landed at Icklingham, probably for the mill, but other villages had turves delivered instead. Nowadays we would call these peat blocks, as peat was a cheaper fuel than coal.

|

|

1813

|

In 1813 Charles Lowe, a prosperous miller at Ixworth, leased Pakenham watermill and its 40 acre farm from the Leheu family for £130 pa. He agreed to spend £400 on improvements, despite the mill being only 15 to 20 years old. He replaced the undershot wheel with a very large breastshot wheel of wood and iron, which also meant that he had to raise the banks of the millpool to bring the water level up to breastwheel height, giving a 10 feet fall.

|

|

1815

|

In 1815 Sir Thomas Gery Cullum was carrying out improvements to the river at Mildenhall.

In 1815 there were floods along the River Lark, and some landowners saw their meadows under water. This was blamed on the River Lark, and so Sir Thomas Cullum sent Mr Bevan to survey the situation. He concluded that in most cases the flooding was no worse than it had been in times past. However, he identified three locations where the river level was normally high enough to prevent meadows draining properly into the river. He proposed that for these three spots it would be possible to build tunnels beneath the bed of the river to carry this water away. Ditches would then take the water away to below the next lock or staunch, where it would drain naturally into the river. Such works can still be seen today at Fornham All Saints, Ducksluice and at West Stow. The 1839 tithe map for Fornham All Saints showed a Tunnel Meadow, which reflected this work.

|

|

1817

|

In 1817 an Act of Parliament placed the Lark navigation under 80 Commissioners. This Act also consolidated into itself all the provisions of the 1699 River Lark Act, and added several new clauses, some of which were to protect the rights of millers along the river.

Some of these provisions included the following:-

If landowners erect gates, then these must not obstruct navigation on the river, nor must any new ditches take water out of the river. Top Water Marks are to be set 6 inches below the average bank level on the river, and the water level is not to exceed these marks. Except in time of flood. Commissioners were to hear appeals, and millers were not to be adversely affected by this regulation. Lark Navigation Proprietor to ensure adequate drainage of land. Millers not to hold back water from the river. However, the ancient Fornham St Genevieve Mill, owned by the Duke of Norfolk, to continue to enjoy traditional privileges. Works on the river to be advertised 3 weeks ahead. Obliges proprietor to provide for mills to be repaired, and for river works not to impair mill operations.

Note that this Act clearly implies that the mill in Fornham St Genevieve was still operating at this time. However, this mill was believed to have been swept away in the late 18th century as part of the emparking of Fornham Park.

The full text of the 1817 Act can be accessed from the River Lark homepage, or can be read here: River Lark Act 1817 (Use your browser's 'back' button to return to this point.)

|

|

1842

|

Some of Sir Thomas Cullum's major improvements to the River Lark were finished in 1842. The Cherry Ground lock was built by Sir Thomas, and once had a plaque stating "TGC 1842". This lock is now within the West Stow Country Park, and has been fenced off because the brickwork is crumbling away. It currently bears an Anglian Water sign calling it Cherry Tree Lock.

The Cherry Ground lock was a key part of the improvements to the river. It was built on a bend where the lock was fashioned into a crescent shape, much longer and wider than the usual locks on the Lark. It could hold 8 gangs of lighters at one time if necessary, lined up side by side. Such a lock justified a full time resident lock keeper.

So Sir Thomas Cullum also built River House nearby for the use of the lock keeper. This was completely demolished in 1979 as part of the preparations for the opening of the West Stow Country Park to the public. The house had stood in ruins for years, and was unsafe. According to D E Weston, this house also bore the Cullum plaque, "TGC 1842".

|

|

Bad weather July 1879 |

|

blank |

|

1879

|

Following a number of years of bad harvests, 1879 was even worse. It was a year of heavy and seemingly continuous rain.

Very wet weather meant that this was a year of disastrous harvests, some fields were not finished until October. Corn rotted where it stood, or sprouted on the stem. English millers had little or no corn to grind. Normally such scarcity would have pushed up prices to provide some return for agriculture.

However, this poor harvest was just the beginning of the end, as cheap American grain began to flood the market after 1878. Steam powered ships introduced in 1860, could now make fast and predictable crossing times over long distances. Such shipments would now become commonplace for food transport.

At the same time, steam power was becoming viable for milling, meaning that mills were no longer tied to rivers or hilltops for wind.

This imported grain was also much harder than English wheat and created a problem since the wind

and watermills could not grind it. A solution appeared in the form of the

roller mill, a Hungarian invention, which could cope with hard North

American wheat. These roller mills could easily produce much whiter

flour than the old stone mills. The large milling companies set up mills on dockside sites as the most economic way of handling imported grain.

The small inland mills would rapidly become less profitable and several would go out of business in the next twenty years.

The brief period of high farming which began after 1850 had now collapsed. Corn growing areas like Suffolk would be in a slump well into the next century, and conditions just grew worse and worse.

The bad weather holding up the harvest is illustrated here by flooding in the Abbey Gardens in July, when the showmen's gathering was flooded out.

|

|

1889

|

Lord Bristol wanted to revive the Lark Navigation and set up the Eastern Counties Transport and Navigation Company to revive James Lee's ideas of 30 years earlier.

A new company was in the process of being formed, to be called "The Eastern Counties Navigation and Transport Company Limited", or the "ECN & TCL", as their new lighters would soon be blazoned.

The Herveys ensured that the first enquiry by the Board of Trade under the 1888 Railway and Canal Traffic Act was held into the River Lark. In August of 1889 the Board of Trade Enquiry opened in Bury St Edmunds. Both their Lordships were in attendance as were representatives of the Bury St Edmunds Borough Council and all the riparian owners on the river. There were no objections to the ECN & TCL taking over the running of the navigation and its subsequent improvement.

Much money was borrowed, the river dredged and straightened and an attempt was made to extend the Lark navigation into Bury St Edmunds itself. The new wharves were to be behind St Saviour's Hospital ruins, where today's Tesco car park stands. Mermaid Pits were used to store water for the locks, and 60 barges and 3 steam tugs were bought.

Things moved swiftly and improvements to the river Lark at Mildenhall began straight away in August 1889, as did the construction of the new wharf at St Saviours. The dredging and canalisation of the river from Fornham Wharf to St Saviours had already begun in July 1889.

Plans were drawn up for a new bridge to carry the Fornham Road by the Tollgate Inn, and for a new lock just upstream of the bridge.

|

|

|

Temple Bridge 1976 |

|

1890

|

In 1890 thousands of tons of goods were brought into Bury St Edmunds along the River Lark before the work was anywhere near finished.

By September the works contract of Gilmour and Wilson ended. They had removed three of the staunches, and converted one to a pound lock. The rest had been repaired. In addition, the Tuddenham Mill Stream had been dredged to allow navigation up to Tuddenham Mill. This work had required a new staunch to be installed on the mill stream.

Despite all that had been done, many people considered that it was obvious that the dredging was incomplete.

|

|

1893

|

In April 1893, Parker's watermill at Icklingham was converted to use electric lighting. A generator was run off the waterwheel. It was the first flour mill in Suffolk to be lit by electricity. Parkers were also to rejuvenate a few local watermills by converting them to roller mills over the next few years.

On August 4th, William Howlett walked the river from Bury to Mildenhall to report on its condition. Work was still being carried out to improve the situation.

The first few stretches had sluices and locks in good order, except, he noted, "the old Tollgate excepted." From Ducksluice to Hengrave he saw plenty of fish. Chimney Mills millpond also had good fish rising. At Flempton Mill, Mr Barbrook was miller.

From Flempton staunch to Fullers Mill Lock, "a grand improvement has been made to the river. It is not the narrow, shallow, ditch-looking place it was, but is now cut out in a proper manner, the sides well shaped, and a good depth. The line of the river has been sloped out right back to the original water line of 70 years since." Trees had to be dug out of the bed of the mill, and new brickwork and locks installed. "Here at this point will be a most excellent reservoir for holding up the water and keeping it to its proper level."

|

|

1894

|

In March 1894, William Howlett again walked the river from Bury to Mildenhall. He approved of the water level and "everything was fair and good", until the Tollgate Lock. Tollgate Lock he called "a complete wreck, and nothing more or less".

Mr Wicks's mill had locks and gates in good order at Fornham. At Fornham Bridge, a new iron bridge had been erected by the West Suffolk County Council. This replaced the old wooden Causeway Bridge which had partly collapsed under the weight of a traction engine in 1890. By at least 1955 the Ordnance Survey maps called this Sheepwash Bridge.

Between Ducksluice and Hengrave mills he saw trout rise. At Chimney Mills Mr Bell welcomed him, but he found the towpath very awkward here.

At Flempton mill Mr Barbrook junior was struggling to keep the old mill going, "as these roller mills take a lot of beating."

Apparently Mr Howlett saw no barges between Bury and Mildenhall, and this was no surprise as traffic seems to have been as low as one barge load a week.

Howlett also noted that the fine old flour mill at Barton Mills had been hired by Parker Brothers, and fully renovated. The old steam engine was put back into service, and the mill now converted to be a roller mill.

As for the Eastern Counties Navigation and Transport Company, it was in deep financial trouble. On 7th December 1894, a receiver was appointed by the Chancery Division of the High Court. He was Mr Bevan, the local banker who had issued the writ. A few days later the business was handed to a new Receiver, Charles Baker, an accountant. He was to try to run the business until April 1895.

|

|

1895

|

In March 1995 Mr Howlett again walked the river. This time he met one barge at Stow Lock. Coal was still apparently being delivered to the sewage pumping station, which can still be seen in West Stow Country Park. There were two Lancaster boilers generating steam to drive the pumps. Deliveries were also made to the Icklingham mills at this time.

|

|

1897

|

For many years the area around Chimney Mills at West Stow had been "extra parochial". Some 7.5 acres were included in none of the surrounding parishes of Culford, Hengrave and West Stow. After an enquiry held in 1896, Chimney Mills was annexed to Culford in October, 1897, following the wishes of Lord Cadogan.

|

|

Joseph Bridge, Engineers

|

|

1899

|

This waterwheel was built in or about 1899, by the firm of Joseph Bridge at their Victoria Street works in Bury St Edmunds. It was for use in a watermill, as can be seen by the display of millstones in the picture. Several watermills were still working along the valley of the River Lark, and Pakenham and Ixworth both had watermills still operating on the River Blackbourne at this time. Some time around 1890, the Chimney Mills water wheel had been replaced with a 20 foot diameter steel wheel made by Woods and Cocksedge of Stowmarket.

A new stone quarry was opened near the Temple Bridge at Icklingham in 1899. In April, several gangs of barges were seen going up to that location to load stone. This must presumably have been gravel and large flints, which is still dug in this area today.

In May, on Whit Bank holiday, the pleasure boat called "Leisure Hour" seems to have sailed from Bury up to Barton Mills with a party on board. This may have been the boat which William Howlett referred to on the river in 1897. It was crewed by Mssrs Capon, Mountain and Forder.

On August Bank Holiday over 40 boats containing day trippers were reported to be on the river between Mildenhall and Temple Bridge, by Howlett.

|

|

1901

|

In February 1901 the Receiver of the ECN & TCL company was discharged, and in September of 1901, an Extraordinary General Meeting of the company was called to wind itself up.

Most of the physical assets of the company had already been disposed of, but it still owned the Navigation rights, and they still had a value.

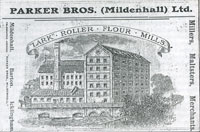

After September 1901 the Lark upstream of Mildenhall was abandoned for barge traffic. The prospective purchasers of the Lark were Parker Brothers of Mildenhall, and they only wanted it to service their own mills at Barton Mills and Icklingham.

In November, the expanding firm of Parker Brothers reopened the Mildenhall Mill.

|

|

Parker Brothers advertisement

|

|

1902

|

The River Lark Navigation and all its rights were finally sold to Parker Brothers of Mildenhall, on July 30th, 1902. The price was just £32, the same cost as just two second hand unpowered lighters.

Parkers sent vessels as far as Kings Lynn, and serviced their own mills by barge up as far as Icklingham.

However, the pleasure boat "Leisure Hour", continued to manage the trip from Bury St Edmunds downstream to Icklingham and back.

|

|

1916

|

Windmills and watermills all had a hard time during the Great War. During World War I, millers were forced by government regulations to grind only animal feed thus limiting their usefulness. The watermill at Chimney Mill closed down in 1916. It would be demolished in 1932.

The staunch at West Row was dismantled by German Prisoners of War during 1916. Tymms 1916 Handbook of Bury St Edmunds was probably rather out of date when it claimed that the River Lark was navigable up to Icklingham.

|

|

1917

|

The silting up of the River Lark was having consequences for land drainage. Meadows above Icklingham were now prone to flooding. On 22nd September the West Suffolk War Agricultural Committee met to discuss the problems.

Witnesses stated that there were 7 mills along the river between Bury and Mildenhall, with their associated millstreams. Millers were being accused of holding back the water which caused flooding upstream. Although the Tollgate Lock was derelict, its existence was still felt to be beneficial for regulating the water level in that area. A witness pleaded for it not to be removed.

|

|

1932

|

The watermill at Chimney Mill at West Stow, standing on the River Lark, had been closed down in 1916. By 1932 there were no water mills working on the Lark. At Chimney Mill the 75 foot smokestack survived, but the watermill itself was demolished on 12th March.

The newspaper report on this event also lamented the state of the river for both fishing and navigation. "Pools once favoured by anglers are now deserted."

|

|

1933

|

Parker Brothers had been mill owners on the River Lark, and in 1902 the firm had purchased the rights to the Lark Navigation so that they could service their mills upstream as far as Icklingham. They had long ceased to use the river for this purpose, and road transport was now used with the railway.

In 1933 William Parker sold the rights to the Lark Navigation, insofar as it was within Suffolk, to the Great Ouse Catchment Board. The Board was set up by legislation in 1931 along with many other Catchment Boards. The new Board had plans to revive the river.

The transaction included the words, "navigation rights to the River Lark, otherwise Burn, together with lands and property" to be transferred from William Parker of the Lark Roller Mills to the Board. The use of the name Burn for the River Lark was still felt to be necessary in such legal documents.

|

|

1943

|

The lock at Duck Mill collapsed in 1943. This name may refer to Ducksluice lock at Fornham All Saints. Flempton Lock also suffered a collapse. There were no resources available to make good these problems because of war time conditions.

However, the military could command such resources, and D Weston reported that a military dam was constructed at Fornham, to strengthen the anti-tank defences of the Lark Valley Stop Line. This dam was apparently removed in 1962.

|

Books consulted:

The Lark Navigation by D E Weston, 1980

Background to Breckland by H J Mason and A McClelland, 1994

The Lark Valley by the Lark Valley Association, c1999

An Historical Atlas of Suffolk: Suffolk County Council, David Dymond and Edward Martin, 3rd Edition, 1999

The Culford Estate, 1780-1935, The Ingham Local History Group, editor Clive Paine, 1993

|