|

Local Coins of the Saxon and Viking Periods

|

312

|

The Roman currency unit of solidus was introduced as one-seventy second of a pound. It was to become the 's' of £.s.d. The denarius was the 'd' of the £.s.d.

|

|

410

|

In the year 410, the cities of Britain were officially ordered by the Emperor Honorius to take responsibility for their own defences. After this the supply of Roman coins dwindled and no new coins of the Empire were produced in England. No coinage of any sort seems to have been minted in England from 411 until about 630. However, we may judge that existing coinage remained in circulation for some decades, and other coinage would have arrived with foreign traders, even if there was no further official money issued here.

|

|

C. 575

|

Late in the 6th century Merovingian Frankish gold coins reached our shores and a purse of such coins was found at Sutton Hoo. These may not represent money as we would use it today, but could be tokens or tributes to cement alliances or treaties with allies.

|

|

590

|

The first Anglo-Saxon coin was struck by Bishop Udehard at Canterbury, but local coins remain scarce for the next 40 years.

|

|

625

|

Around 625, a great aristocrat, probably King Raedwald, was given a ship burial at Sutton Hoo. Part of the treasure laid to rest in his grave was a purse of Frankish Merovingian gold coins. In the past it had been thought that this must have been a gift from a Frankish king or noble. However, we now know that such coins had been circulating in England for nearly 50 years. Therefore it is just as likely that they were collected within this country, but could still represent diplomatic gifts or tribute.

|

|

630

|

Coinage struck in England became more widespread when continental coinage began to decline in its gold purity.

Anglo-Saxon gold thrymsas were minted, at first copying Frankish or Roman coins. The term thrymsa is thought to be a curruption of the word tremissis, weighing 1.3 grammes and worth one-third of a solidus.

|

|

650

|

By 650 there were more domestically made coins in circulation in England than foreign coins. Foreign gold coins were declining in gold purity. The mints were probably only in Canterbury and London in the 630s and 640s. In about 650 a series of coins were struck at York.

|

|

660

|

The first coins to be struck in the east of England were pale gold shillings of the "Constantine" type. About a dozen have so far turned up, and may originate at Peterborough. However, from 675 until 700 there were no further coins produced in East Anglia.

|

|

675

|

Gold coins were largely replaced by silver as gold became scarcer. In Frankia the gold coins being produced had declined to only 20 percent purity by this time. Subsequent coinage was thus virtually entirely silver until 1257. In England the new silver coins seem to have been called penningas or pennies for the first time. Today's collectors, however, still call them sceats, pronounced "shats", a term which dates to the 17th century.

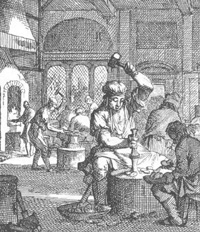

These first pennies were struck from cast silver blanks, and were smaller and thicker than those produced after about 757 under King Offa. These first round pennies would sit comfortably within the area of a little finger nail.

All coins were produced by hammering a piece of metal, called a flan, between two engraved dies until the 16th century.

|

|

690

|

Series C of Primary Sceattas are known as East Anglian Runic series. North notes that these were possibly of Kentish origin, and Dr Mark Blackburn suggests that there were no East Anglian coins produced from 675 to 700 AD.

|

|

710

|

According to Dr Bailey, the first new East Anglian coins were those called Series R. These have been said to derive from the earlier Series C, but are described as "crude and stylised runic types." The moneyer was EPA, spelled in runes, and the mint location was possibly at Ipswich. Series R is dated to the years from 710 until 740.

|

|

720

|

On the continent the coinage was changing. Under the Carolingian kings silver coin flans were no longer being cast. They had discovered how to roll and hammer silver into thin sheets. Coin flans were now cut from these sheets, and were thinner and larger than the old cast flans, for the same weight. This gave a bigger area for the coin design to cover, and the king's name became added to their coins. This innovation did not reach England until 757.

|

|

Late series R sceat/penny

|

|

735

|

This example of an East Anglian Series R Sceat shows a degenerated form which dates to 735 to 740. The inscription has become garbled, and only EP is visible.

|

|

740

|

After 740 the series R sceattas from Suffolk are made by Wigraed and Tilbert, both moneyers probably at Ipswich.

A type known as series Q arose for 10 to 15 years in Norfolk, probably somewhere on the fen edge. It featured many strange bird and animal motifs.

|

|

749

|

An East Anglian king known almost exclusively from his coinage alone was called Beonna, who ruled from 749 to 757 approximately. This was the first time in East Anglia that the king's name was included on the coins. It seems that the idea originated in Northumbria. Beonna's moneyer was called EFE, and 150 coins in 3 types were found in a hoard at Middle Harling. Another moneyer was WILRED.

|

|

757

|

In the reign of Offa, the new flatter and thinner silver penny was probably introduced into England. Offa also introduced his portrait on to English coins for the first time. He depicted himself as a Roman emperor, and minted these coins in Canterbury and London.

Collectors may call these the first pennies, but Dr Mark Blackburn believes that the older small "sceats" were already being called pennies in England at the time.

The word penny may derive from the Germanic pfennig, but deniers were also used on the continent. The penny was the main denomination up to Edward III but has still remained in use after that time up to the present day.

|

|

760

|

Some time in the 760s a coin was issued by Wilred, who had minted for Beonna, but now it was made in the name of Offa of Mercia. This indicates that Offa had now taken power in East Anglia. Also probably minting at Ipswich was the moneyer called Botred, also making coins in the name of Offa Rex. The king's name was inscribed in latin or Roman text, while runic text was used for the moneyer's name.

|

|

790

|

Because the coinage of East Anglia was being minted in the name of King Offa of Mercia, we do not know much about the succession of the East Anglian royal house during this period. East Anglian moneyers were Aethelwald, Ecgbald, Eadnoth and Earwerht, all minting for Offa.

King Aethelrad of East Anglia probably died during the 780's, and at some point he was succeeded by Aethelberht II.

|

|

Silver penny of Aethelberht II

|

|

792

|

In about 792 Aethelberht appears in the coin record. A silver penny naming Aethelberht "REX" was minted by a moneyer called Lul. Not since Beonna in the 750's had any East Anglian dared to claim kingship on a coin. Not only this, but the coin also showed a wolf suckling two children, an allusion to Julius Caesar and the Roman Empire. Only the Wuffing dynasty of East Anglia had claimed to be descended from Caesar in their mythological genealogy. Aethelberht was clearly sticking his neck out, and this had grave consequences for him in 794.

In Mercia, Offa revised the weight of his coinage from 1.3 grammes to 1.6 grammes in 792. However, Aethelberht's coins remained at the old standard of 1.3 grammes.

|

|

794

|

Aethelbert II, King of East Anglia, was killed at Sutton Walls, near Hereford by Offa, King of Mercia.

Perhaps even Lul came in for retribution from Offa, as he also quickly seems to have issued another coin, identical to the first for Aethelberht, except that the name Aethelberht was replaced by "Offa Rex". Offa even retained the wolf and children symbol. This also was minted at the pre-Offa standard of 1.3 grammes.

|

|

796

|

The Great King Offa of Mercia died, having built Mercia up to control or influence all of England south of the Humber, including East Anglia. With the death of Offa, East Anglia started to assert some independence again, but this would take another 20 years to achieve.

In Mercia the kingship was taken up by Ecgfrith, Offa's son, but he died within a few months. Coenwulf, a descendent of Penda's brother, now became King of Mercia, and would rule that Kingdom from 796 to 821.

Coenwulf of Mercia continued to exercise overlordship of East Anglia. However, King Eadwald of the Eastern Angles now minted a certain amount of coinage in his own name.

About 15 coins are known with Aedwald's name from the period 796 to about 800, and probably represent another attempt by East Anglia to throw off Mercian control. The moneyer was Eadnoth.

However, the East Anglian moneyer Lul seems to have made coins named for Coenwulf from 796 until 821.

|

|

800

|

Although coinage now included the name of the King, the Moneyer's name or initials continue to appear on coins.

This was necessary in order to trace the origins of coins of below the required standard of silver content. These names continued on coins until about 1280.

|

|

821

|

King Coenwulf, the king of Mercia, and overlord of East Anglia, died near the Welsh border. He was succeeded by his brother Coelwulf.

There were at least six moneyers in East Anglia during the reign of Ceolwulf, which lasted only two or three years. The sites are not named on the coinage, but the moneyers were as follows:

- Wihtred

- Hereberht

- Wodel

- Werbald

- Botred or Fotred

- Eadgar or Eacga

In about the same year Aethelstan may well have become King of East Anglia. Other authorities place his rule as beginning several years later, but only the coinage is available for interpretation. The date of 821 relies upon a ship type penny minted by Eadgar for Aethelstan, now in Norwich Museum. King Aethelstan would rule in East Anglia until 845, and at first he was subject to the Kings of Mercia.

|

|

825

|

King Beornwulf of Mercia was succeeded by one of his ealdorman, a man called Ludica. Some of the East Anglian moneyers continued to strike coins for him, so the East Anglians still acknowledged Mercian power.

|

|

827

|

Ludica, king of the Mercians, was killed along with his five leading ealdormen. Roger of Wendover wrote that this was by order of King Ecgberht of Wessex.

From 827 the East Anglian moneyers produced no further coins for Mercia in the name of Wiglaf, who now took over in Mercia. On the contrary, the East Anglians now began to produce coins for their own local king Aethelstan, who now enjoyed Ecgberht's support.

|

|

839

|

Whatever his origins, the King of East Anglia was called Aethelstan at this time, and during the 830s his coinage included the words 'REX ANG', or King of the Angles.

|

|

845

|

At some point around this time, King Aethelstan was succeeded as King of East Anglia by Aethelweard. It may be that the East Anglian Aethelstan had died. But if he was the same man as the Aethelstan who became King of Kent in 839, then he may have handed the defence of East Anglia to Aethelweard around 842. East Anglian coinage now featured Aethelweard as 'REX' until about 855. Some 60 to 70 coins are known for Aethelweard, but apart from his coins he is not mentioned in any known written source material.

|

|

King Edmund Penny

|

|

855

|

According to the Annals of St Neots, an early 11th century record, King Edmund was crowned King of East Anglia at Bures. He ruled East Anglia until the coming of the Danish invasion in 869.

From 855 to 870, Edmund's coinage was in circulation with his name on them. None of these coins show a portrait of the king, but a large number of coins are known today from this monarch. Spink's Coins of England states that One side had an Alpha or A, the reverse had a cross with pellets or wedges. But other types are now known. The coin shown here appears to show Omega and a cross, rather than alpha. J North in English Hammered Coinage Volume 1 does give an example similar to the illustration here, and he describes it as "very rare" for King Edmund. The motif is described as omega with latin cross.

We can see that it is easily possible to become confused with the memorial coinage issued from about 895 to 918 in Danish East Anglia some years after Edmund's death as a martyr. Examples of the later memorial coins also show alpha.

|

|

869

|

In 865 the army of the Danes landed in England, and by 869 they had taken over East Anglia, making it a Viking Kingdom until 927. The Vikings did not use coinage as such, although coins could be found circulating in lands under their control. Theirs was a bullion using zone, where pieces of silver were valued by weight, not by face value. Hack silver and coinage were equally valued, so long as they weighed the same, and seemed to be pure. One unusual feature of this system was that Islamic dirhams and part dirhams were widespread within viking areas.

|

|

870

|

Only five coins are known (as at 2009) of an East Anglian king called Aethelred around 870. Mark Blackburn has suggested that he may have been a puppet king who followed King Edmund, but that in practice the Danes were overlords of the kingdom. Coins were minted for him by Sigered and Heahmod.

Also during this period from about 870 to 880, coins of "temple" type were minted for a king Oswald, probably in Ipswich. He was also probably only king at the Danish pleasure.

|

|

880

|

In 879 and 880, the Danish leader Guthrum brought his followers to settle in East Anglia. He had agreed with King Alfred the Great that he would accept Christianity and live in peace. His baptismal name was Aethelstan, and he now ruled East Anglia as its king. In 880 he now issued coinage as Aethelstan Rex which was of the christian type used by Alfred. Guthrum maintained the weight standard of 1.3 grammes as used by Edmund before him, while in Wessex Alfred was using 1.65 gramme weight coins.

|

|

890

|

By 890 Alfred had held Mercia and Wessex and established a balance of power with the invaders.

Alfred found time to translate Latin texts into English and had these distributed throughout his lands.

Coins were minted naming Alfred King of the English, but of course, in practice, this excluded the Danelaw, north and east of a line from London to Chester.

|

|

Memorial Penny from Thetford |

|

895

|

By now the Danes had largely converted to Christianity, and within thirty years of Edmund's death, they themselves were issueing coinage in his memory. Guthrum was dead, and the Edmund memorial coins mention no current king, so we do not know who was ruling East Anglia at this time.

The Edmund memorial coinage of Danish East Anglia was issued from 895 to 915, and there were no other coin types made in this period. Another memorial coinage was also produced in memory of St Martin of Lincoln.

The coin shown here was found at Thetford in 2002. J North in his English Hammered Coinage describes this as possibly dating to the later period of Viking occupation of about 905 to 910, because the legend or lettering is "blundered", that is to say that it looks OK but makes no sense that we can discern today.

Another memorial coin, with a better legend in memory of Edmund, was copied for the 1907 Bury Pageant medallion. The moneyer was OTBERT, but the location of the mint is unknown.

It is entirely possible that the mint was in Thetford, a major town at this time. Possibly it was as big as, or bigger, than either Norwich or Ipswich in the late 9th Century.

Meanwhile Beodricsworth, the settlement to become Bury St Edmunds eventually, was probably a small community, possibly living on its memories of being a royal vill from the time of Sigbert, but now of no real importance.

|

|

The Cuerdale Hoard

The Cuerdale Hoard |

|

905

|

Viking loot now known as the Cuerdale Hoard, was hidden in Lancashire. Many Anglo Saxon and Viking coins were included in this hoard. About 1500 of the coins were from East Anglia, of the type known as the Saint Edmund memorial coins.

|

|

916

|

Around 916 a hoard of coins was deposited at Manningtree. The Manningtree hoard contained about 80 coins which were of the St Edmund memorial type. These were from the later phases of this coinage, but it still shows that St Edmund was a growing cult, and that East Anglia was still independent enough to issue its own local currency.

It is interesting to note that viking coins of this era all tend to show fewer literacy skills than Anglo-Saxon coins of the same date. As time passed the viking coins got even worse for spelling to such an extent that the legends became meaningless. This probably confirms our view that the vikings did not value literacy, and probably did not use written records to any extent.

|

|

920

|

By 920, however, the viking coinage seems to abruptly disappear from the East Anglian scene. A hoard of coins deposited at Brantham in about 920

contained only coins of Edward the Elder. There were no viking coins at all. This seems to indicate that Edward had held a massive re-coinage which resulted in all earlier coins being exchanged at his mints to be melted down and re-issued in his name. They were also issued at the new higher weight standard which had hitherto not been adopted within the Eastern Danelaw.

|

|

959

|

Edgar became King and appointed Dunstan Archbishop of Canterbury in 961. Dunstan embarked on a programme of Church expansion and reform based on the new French ideas of monastic life.

When Edgar became sole king of England a uniform coinage was instituted throughout the country. A royal portrait was on one side. The reverse had a cross with the name of the mint as well as the moneyer. Under Eadgar most fortified towns of burghal status were allowed a mint, but all 50 locations produced identical design coins. The number of moneyers depended on the size of the town. Bury St Edmunds does not seem to have qualified to have a mint at this time.

|

|

973

|

After 973 the Kings were in full overall control of the English economy. King Edgar had himself crowned as King of the English at a ceremony of re-coronation. At the same time he issued a new coinage across the country.

Every few years the Kings would now introduce new coinages as a tax raising enterprise. Everybody had to bring in their existing coins to be replaced by new coins. In this way the traders would have to pay the moneyer about 10 or 15 percent to have his coins replaced. Most of this tax was passed on to the King.

|

|

King Ethelred the Unready

|

|

997

|

King Aethelred II ruled England from 978 until 1016, and is better known to us as Ethelred the Unready. The coin illustrated here is dated to around 997 to 1003, and is of his Long Cross type coinage. This example was minted by Mana of Thetford.

|

|

King Cnut or Canute

|

|

1020

|

King Canute allowed the town of Bury to become a fortified borough. Coins issued by King Canute (1016-1035) were widely minted in places which included London, Lincoln, York, Stamford, Cambridge and Thetford. At Thetford, the moneyers included Aelfwig, Brunston and Telfwine, and the coins were short cross type silver pennies. At this time Bury was not a centre of coin production.

|

|

Elfwine of Thetford

|

|

1029

|

Thetford was an important town throughout the Viking periods. It had been a major Winter layover location for the invading Danish army in 865 and grew in strength since that time. It had been a minting centre for many years. The coin shown here was made by Elfwine of Thetford for King Cnut's government in the years between 1029 and 1036. It is only one example of many coins minted by many moneyers at Thetford in these times before the Norman Conquest.

|

|

King Edward the Confessor

|

|

1044

|

Edward the Confessor also granted the town of St Edmund its own mint, and its currency bears the first documented use of the name St Edmunds Bury. J North states that the legend was EDMUND and the moneyer was Morcere.

|

|

First coin minted at Bury |

|

1048

|

By 1048, Edward the Confessor must have granted the town of St Edmund its own mint, and its currency bears the first documented use of the name St Edmunds Bury.

The first coin types struck at Bury under King Edward are described as small flan, and only 3 examples are known. This series is dated by Seaby's as beginning in 1048, and running for two years. Five more patterns were struck at Bury from 1052 to 1065.

North states that the legend was EDMUND and the moneyer was Morcere. R J Eaglen quotes variations like ED, EDHUN, EDM, EADM, EADVM, and EAD.

The evidence of the coinage clearly exists, and presumably it must have been authorised by royal writ, but none survives. The first surviving writ granting the Abbey a mint comes in 1065, as part of the authorisation of Baldwin to take up the post of Abbot after the death of Abbot Leofstan.

|

|

Minted at Thetford by Estmund

|

|

1053

|

Thetford continued to be an important town, and coinage made there remains plentiful today. This example was made by the Moneyer Estmund, and shows the reverse side of the coin shown above at 1044. From this pattern it is described by J North as coming between 1053 and 1066.

The inscription is fairly easy to see, particularly if you click on it to get an enlargement.

It reads ESTMVND ON DEOT, starting at bottom left.

DEOT or DEO is the abbreviation used at the time for Thetford.

ON means "of" or "from".

Many other inscriptions on coins made by hand are harder to see as they may be quite worn, or poorly struck in the first place.

|

|

1065

|

At Bury, Abbot Leofstan died and Baldwin was appointed to the post of Abbot.

King Edward issued his writ appointing Baldwin as Abbot, (S 1083), together with a writ confirming to the monastery the sokes of the eight and a half hundreds, (S 1084) and a further writ granting Abbot Baldwin the right to one moneyer in the town. This last writ is reference number S 1085 in Sawyer's catalogue of Anglo-Saxon charters.

From the coin evidence shown above, it is believed that a royal mint must have already existed in Bury since about 1048, and that this writ was merely to transfer the power into Abbot Baldwin's jurisdiction. This confirms Bury's importance as a trading centre before the conquest. At first it seems possible that the mint was located close to the Sacrist's office within the Abbey.

|

|

1066

|

By this time, there were about 70 mints active in England. Since the time of King Eadgar in 973 the name of the mint had to be put on the coins. King William the Conqueror would allow all 70 existing mints to continue working after the Conquest. It had become the Anglo-Saxon tradition that the silver penny was the only coin struck, but at the time it was fairly valuable. When smaller units were needed, pennies were cut into halves or quarters quite legally by merchants and traders.

|

Prepared for the St Edmundsbury website

by David Addy, July 1999

Books consulted:

Seaby's Coins of England

Coincraft's Standard Catalogue of English Coins

J North English Hammered Coinage, Volume 1

Dr Mark Blackburn "Money in Anglo-Saxon East Anglia" Sutton Hoo lectures 10th October 2009

Specimens:

The specimens shown are from private collections.

|