|

|

|

The measuring of time has been an issue since pre-historic days. In these pages we will not deal with sundials, water clocks, time sticks, or other ingenious devices. However, it is worth noting that an early reference to a water clock, located in the Abbey of St Edmund at Bury, was made by Jocelin of Brakelond in his chronicle. He recorded that in 1198, a fire in the shrine was fought by monks fetching water from the rain water tank and the clock.

The first mechanical clocks in this country were used in monasteries, and came after about 1275.

The main source of information on local timepieces is to be found in 'Suffolk Clocks & Clockmakers' by Arthur Haggar and Leonard Miller, published in 1974. A Supplement to this work was published in 1979, containing additions and corrections to the 1974 listings.

These pages will deal with clocks made in and around Bury St Edmunds. The famous Gershom Parkington collection, described below, was not intended to be a local collection, but a representation of all the best types of time measuring instruments. Here, we will pick out only local examples for consideration.

|

|

The John Gershom Parkington Memorial Collection of Time Measurement Instruments In 1953, the Bury St Edmunds Borough Council was left a notable collection of clocks and watches in memory of John Gershom-Parkington, (1920-1941), who was killed during the Second World War. The collection was bequeathed by his father, Frederic Gershom Parkington, better known as just Gershom Parkington. Frederic had died on 23rd January 1952, in Jersey. The Jersey Heritage Trust has summarised the provisions of his will as follows: " Will and Testament of Frederic Gershom Parkington, known as Frederic Gershom-Parkington, of 5, Douro Terrace, St Helier. Desires to be cremated and have his ashes buried with his wife. Bequeaths to his late violinist, Tom Jones, his music and quintette arrangements; to the town of Bury St Edmonds, all time pieces and books relating to the measurement of time in memory of his son John Gershom Parkington who was killed in the last war. Dated 22/12/1951." The London Gazette of 13th March, 1953 publicised the existence of the will, and asked for claims against it to be made by 15th May, 1953. Once the council of Bury St Edmunds was made aware of the bequest, it had to consider if it would accept it, and how to make arrangements to house and display it. The Gershom Parkington Quintette used to be a household name, playing light music on the wireless in the years after 1925. Its founder and leader was one of the Parkingtons who ran a successful tailoring business at 29 Abbeygate Street, Bury St Edmunds, which had served generations of Bury's inhabitants. Frederic was born in 1886, seven years after the rest of his brothers and sisters. His parents gave him the name Gershom from the Bible, where it is said to mean 'a little surprise', although he used to say afterwards that it really meant ‘the unwanted one'. He was a gifted cellist, and he trained at the Royal Academy of Music. Thus he avoided joining the family business to become a professional musician. He conducted the local orchestra at Bridlington Spa for a time and broadcast for the BBC for almost thirty years. Professionally, he always used the name Gershom Parkington. He was so popular that in 1934, W D and H O Wills included him as number 15 of their series of 50 Cigarette Cards called "Wills Radio Celebrities." |

|

This picture of T W Parkington's tailor's shop at 29 Abbeygate Street, Bury St Edmunds, was taken from the firm's advertisement in the Town Guide Book for 1955-1956. Kelly's Directory for 1892 had described the business thus:- "Thomas Wilding Parkington - military tailor and outfitter, hunting breeches, liveries and riding trousers, 29 Abbeygate Street." In Kelly's Directory of Suffolk for 1900, the entry was :- "Parkington, TW and Son, Tailors and Outfitters, 29 Abbeygate Street." |

|

As a hobby, Gershom Parkington bought rare clocks, watches, sundials and sand-glasses, largely through a specialist dealer named Percy Webster, of Queen Street, Mayfair, and built up a notable collection with a national reputation. It was this collection which he left to the town of his birth on condition that it was named the John Gershom Parkington Memorial Collection.

By agreement with the National Trust the collection was, at first, installed in the Queen Ann house next to the Borough Offices and now known as Angel Corner. |

|

The Connoisseur Year Book for 1958 included a catalogue of the John Gershom Parkington Memorial Collection of Time measurement Instruments at Bury St Edmunds. It was compiled by S Benson Beevers and it was reprinted as a catalogue to be sold to visitors to the collection in its home at Angel Corner in Bury St Edmunds. The catalogue grouped the items under the major headings of "Mechanical", such as clocks and watches, and "Non-Mechanical", such as Quadrants, Sundials and Nocturnals. As far as we know, this was the first catalogue ever produced of Parkington's collection. A new catalogue was produced in 1979. In 1974 the collection passed to the successor authority, which was the St Edmundsbury Borough Council. The clocks continued to be on display at Angel Corner. According to the 1979 catalogue of the Collection, the Borough Council had already owned a collection of locally made clocks and watches, which was merged with the Gershom-Parkington Collection. The house known as Angel Corner seems to have been officially given this name in 1956. The clock collections were joined there by the Bury and West Suffolk Records Office. The records were there until 1973, the clocks until 1993. From 1993 to April 2006 the Clock Collections were on display at the Manor House Museum, until that museum closed. From 2007 there is a new gallery displaying the clock collection to be found in Moyse's Hall Museum. Many of the clocks illustrated in these pages are taken from the Gershom Parkington Collection. However, it should be emphasised that the collection itself was never meant to be a local collection, although the clocks shown here are purely those of local interest. Other clocks shown on these pages are from dealers' catalogues and books. |

|

THE LANTERN CLOCK In Tudor times the production of clocks in England was in the hands of foreign craftsmen. Not until about 1620 did the first distinctively English clock design appear, and it is called the Lantern Clock. The typical Lantern Clock is made of brass, and resembles the shape of the old lanterns, and it is usually reckoned that its name was derived from this similarity. Haggar and Miller are inclined to doubt this theory, preferring a derivation from the old term for brass, which was "latten" or "latten metal." They cite old wills which refer to latten clocks specifically. Although they resemble lanterns, they were weight driven, and needed to be wall mounted so that the weights could hang below them. Lantern clocks came in two basic sizes. The largest stood 14 inches high and carried a striking mechanism. At first they had a wheel balance, but after 1657 a short bob pendulum was used. They had an hour hand, but no separate minute hand. Many Lantern clocks were made in Suffolk in the second half of the 17th century, but they continued to be made in Suffolk into the middle of the 18th century as well. Older wheel balance lantern clocks and short bob clocks also got converted to long pendulum control in this period. Ornamental fretwork was a feature of these clocks, and in Suffolk many makers favoured a design of crossed dolphins. In Bury, such clocks were made by Mark Hawkins and Richard Rayment.

|

|

LONG CASE CLOCKS Long Case clocks first appeared around 1660 in England, but no Suffolk maker is known to have been making these earliest types. The earliest Long Case clock made in Suffolk dates from about 1700. The Long Case clock is the type which became generally known in the late 19th century as a Grandfather clock, following the popular song of that name, written in 1864. This type of clock encloses the entire length of the hanging weights and long pendulum within a wooden case. The clocks 'works' is also enclosed within a hood with a glass front to reveal the clock dial. It usually stands on the floor and can be 6 or 7 or even 8 feet tall. Such clocks were made by the Ipswich based Thomas Moore after 1710, and Moore is now regarded as the best Suffolk clockmaker. In Bury the best makers were William Hawkins and Richard Rayment. However, nearly all the later clockmakers produced Long Case clocks. They could be made to suit all pockets, and the case was dressed up to meet the appropriate price point. Country makers tended to use oak cases, and to make their clocks less tall, so that they could fit under lower cottage ceilings. Large country houses needed something on a bigger scale, with more ornamental finish. The example shown here is a fairly basic clock, but being made by John Pace of Bury in the early 19th century, it was of such quality that it still keeps good time today. |

|

BRACKET CLOCKS These clocks can also be called Table Clocks, and at the time were also called Spring Clocks. In 1764, Bilby Dorling advertised that he could be found "at the sign of the Spring Clock in Cook Row", in Bury St Edmunds. As the name suggests, they were powered by a spring put under tension, rather than by long hanging weights. This made them difficult and expensive to make compared to the older types of movement. Thus in Suffolk the makers produced fewer of this type than the simpler mechanisms. However, in Bury, the fine workshop of Richard Rayment certainly produced Spring clocks after 1740. This example is by William Last of Bury St Edmunds from the early part of the 19th century. The mainspring having broken, it has been repaired in the last few years.

|

|

PARLIAMENT CLOCKS OR TAVERN CLOCKS OR WALL CLOCKS In 1797 an Act of Parliament imposed a tax on clocks and watches, under William Pitt. The tax was 10 shillings a year for every gold watch or enamelled watch. For every silver or metal watch the tax was 2/6 a year. Every clock placed in or on a dwelling attracted a tax of 5 shillings a year. In anticipation of this Act, it was once believed that there was a rush to install "Act of Parliament" clocks before the tax was imposed. After the tax, it was said that they were installed in public places to replace the private timepieces which were now too expensive to afford. However, there had been a need for reliable public clocks in Taverns, inns, and public buildings for at least 50 years prior to that date. In fact, the tax was repealed after two years, so a genuine Act of Parliament clock can exist only from 1797 to 1799. Clocks usually given this name are wall mounted, and have this distinctive 'drop trunk' below the dial. A very early example of such a clock was reported by Haggar and Miller to be hung in the vestry of St Mary's Church in Bury, made by George Graham of London. It is dated to about 1720. An example from Bury was made by Giffin Rayment, who died in 1769, nearly 30 years before the notorious Act of Parliament which was said to have named these clocks. By the 1790's some smaller wall clocks were produced, sometimes called Norwich Wall Clocks.

|

|

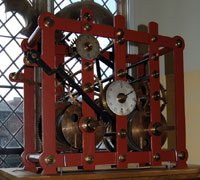

TURRET CLOCKS Turret clocks were built on a completely different scale to other clocks. They were made to drive the large hands and dials of church clocks and clocks installed outdoors on large public buildings. Usually there would be the need for a striking mechanism large enough to drive a hammer on to a large church bell. The oldest turret clock is said to be at Salisbury Cathedral, where there is a record dated 1386. At Walberswick there is a record of such a clock dated to 1426. These clocks were probably built by a good local blacksmith, under the direction of a monk, or specialist travelling artisan. The turret clock shown here is from Long Melford School. Made in the 19th century, it is on display in Moyse's Hall Museum.

|

|

SKELETON CLOCKS A skeleton clock is built to show off the internal workings of the clock. The body is built of ornamented brass fretwork or shaped struts, and it often stands on a mahogany base, below a glass dome, or inside a glass case. Elaborate design features could be included to show off the skill of the maker. In Bury the main maker of this type of clock was John Pace in the early and middle 19th century. Pace produced some deliberately unusual design ideas into his best skeleton clocks to show off his inventive nature. The example shown here is taken from Haggar and Miller,s book entitled "Suffolk Clocks and Clockmakers", and shows one of John Pace's creations. However, a small number of skeleton clocks have been found which were made by Benjamin Parker, a gunsmith in Churchgate Street in Bury, also from the mid 19th century.

|

1727/29 |

WATCHES Here we are talking about pocket watches, as no wrist watches existed before 1868. Strangely enough, watches did not evolve out of the building of clocks. Watches have been made just as long as clocks. The earliest Suffolk watch dates from 1630, and is by W Houlgatt at Ipswich, and is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Large numbers of watches were made and sold from this date right through to the 19th century. By about 1780, such was the demand for watches, that they were factory made, and local clockmakers probably only installed factory movements in factory made cases of varying qualities. In October, 1791 T & W Chaplin of Cook Row in Bury were advertising in the Ipswich Journal for a "good Watch Finisher."

|

|

"Time Measurement Instruments- catalogue of the John Gershom Parkington Memorial Collection" 3rd edition of 1979 Information first prepared by David Addy, 27th April 2006

|

| Go to Clocks Homepage | Updated 22nd October 2007 | Go to Home Page |